Motion sickness in virtual reality is a real problem – one that there has been only minor success in alleviating. Research has been done into using electrodes, or even virtual noses, to counter the problem. Now a pair of professors at Columbia University (Steven Feiner and Ajoy Fernandes) are investigating reducing the field of view as another solution.

FoV is dynamically and ‘subtly’ altered in response to visually perceived motion, said the pair. It is the disconnect between perceiving movement around you while remaining physically still that causes motion sickness (the disconnect between visual and vestibular cues). The system can be ‘easily’ applied to existing headsets and does not decrease the users’ sense of presence in the virtual environments.

The team specifically targeted scenarios in which users move in the virtual world in a way that differs from how they move in reality: for instance, games. To avoid spoiling immersiveness, the system only alters the FoV in situations where a large FoV would be likely to cause motion sickness, and restores it when this sickness is less likely to occur.

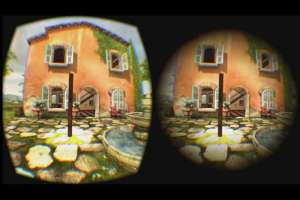

Feiner and Fernandes developed software that acts as a pair of ‘dynamic FoV restrictors’; it can partially obscure each eye’s view. Work was done on how much of the view should be obscured and how quickly.

During a multi-day study, 30 participants were divided into two groups: one without the software and one with. These groups were then reversed on the second day. Participants said that they felt more comfortable when using the restrictors; they also stayed in the virtual environment for longer.

Two types of restrictors were used, one of which was designed to be more subtle. Most of the participants who used the more subtle variant did not notice them, and those who did said that they would prefer to have them in future VR experiences.

Analyst Comment

This is a somewhat surprising result considering that all who work in this field are striving to increase the FoV for their users. Typically, we correlate a wider FoV with a better performance of the headset. While this is still true for a scene without any motion, it seems incorrect for any motion-based content. So far, Oculus has seemed to follow the idea of faster refresh rates as the solution to solving this issue. Maybe their approach in conjunction with this Columbia research could create a better headset? Maybe we will even need another idea to make it work for most users? Either way, I am looking forward to testing this out some day. – NH