The webinar was called “TV’s Production Revolution: The Rise and Rise of Virtual Production” and was introduced by Kate Russell and included the following panel who introduced themselves:

- Kate Gray – NTT Data is a provider of technology and infrastructure. The ‘NTT Disruption’ group uses virtual technology for a range of events.

- Steve Jelley – Co-founder of Dimension which is a specialist in virtual production with motion capture stages, LED walls and artificial photorealistic worlds for content creation.

- Ian Milham – Industrial Light & Magic – the industry has evolved from matte painting on glass to virtual productions which changes everything. Milham was virtual production supervisor on “The Mandalorian”

- Neil Graham – Sky – He coordinates activities in virtual production at Sky and has also worked on VR content as well as traditional film content. Seven months ago the firm set up a virtual production group.

Rather than go through the particular questions and answers, I’ve summarised some of the conclusions of the panel and things that have been learned. The panel talked about the virtual sets as ‘volumes’ and that seems to be term used. I’ve also integrated answers from audience questions.

Change in Workflow

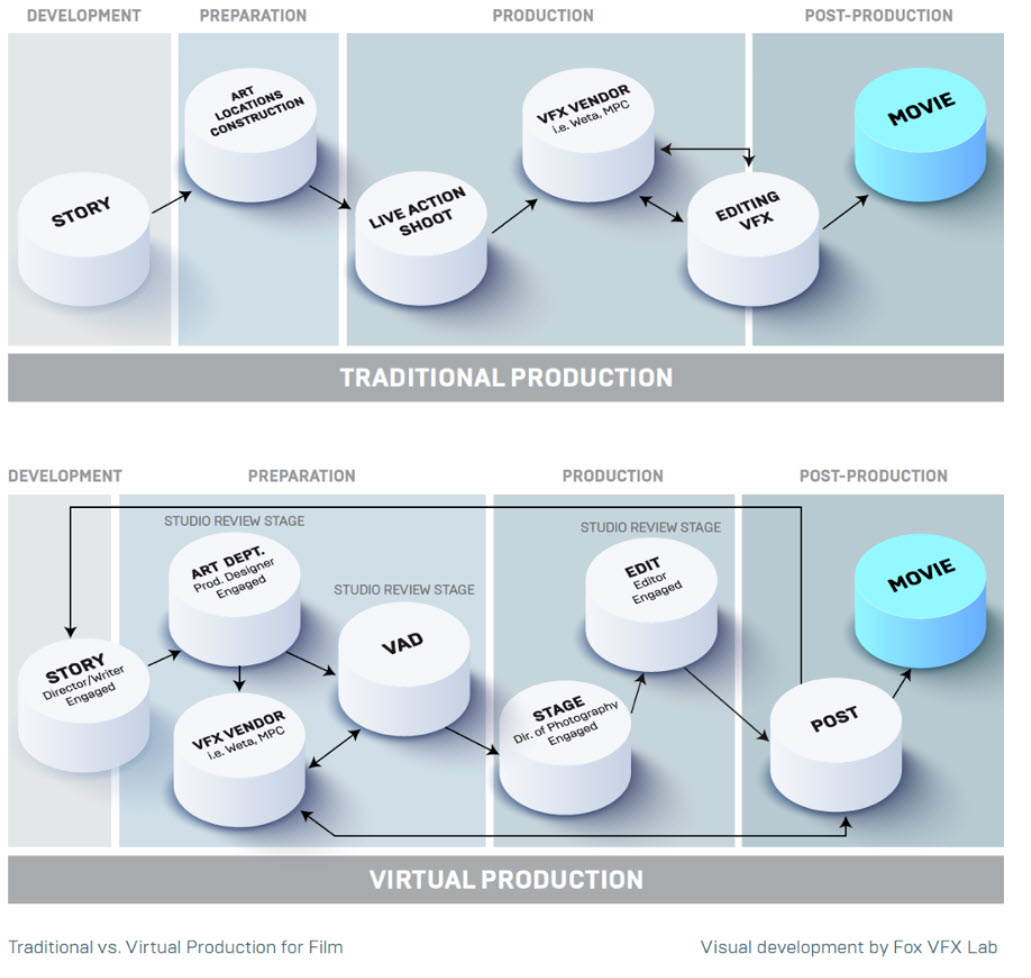

Virtual production is a big change in the workflow of traditional techniques using greenscreens/chromakeying. Traditionally, the actors were captured in greenscreen and then in post-production visual effects (VFX) and backgrounds were added. That can still happen, but the use of LED walls means that backgrounds and effects have to be developed before the capture of the actors. That can even change the writing process and Graham said that his group helped a writer to develop a special VR environment that he had in mind with virtual characters and he could use that to trial the script and said that a process of development that took just a month or so would have taken a year in a traditional workflow.

Working on greenscreens is really tough on actors and Milham said that there is a kind of ‘imagination tax’ on efforts that make things much more difficult. In virtual productions, many camera positions can be planned and rehearsed before the event so more shots can be made in a shorter time, but shots can also be changed easily if the scene comes out differently than expected. Many more camera shots can be made in a single shoot. Lighting can also be pre-planned in detail.

If VFX is going to be added, that needs to be taken into account in virtual production – for example, it may be important not to get too tight in framing to allow for later content addition. That means that the VFX function needs to be included in VR production – and that highlights how collaboration and coordination can be and must be better to make VR work better. Lighting also needs to be well integrated.

Over the whole project, with virtual production there can be a strong ‘editorial thread’ from set design, photography and lighting planning and through to any final VFX.

VR production also means that you can access virtual locations that might be dangerous (i.e. a war zone) or difficult to access (e.g. the rose garden in the White House).

Figure 1: Virtual production changing the pipeline. Source: The Virtual Production Field Guide.

Figure 1: Virtual production changing the pipeline. Source: The Virtual Production Field Guide.

On The Set

On the set, there has been a concern that jobs could be made redundant but the reality is that lighting technicians (or gaffers in the jargon) are still needed, although things have changed. For example, you can change the lighting by moving or turning down the sun in a virtual scene!

During filming, time and cost pressures can be high. In a traditional VFX process, taking time to fix a problem in an environment can take time, but on the set things have to be fixed very quickly – sets operate in periods of 1, 2 and 5 minutes. ILM uses a ‘brain bar’ which is a set of staff with workstations working on motion capture, with a colorist and a layout specialist to ensure consistency between the real and virtual world.

One of the challenges in chromakeying is in avoiding reflective materials because there may be inconsistencies if reflections are not correctly mapped. That becomes much less of a problem and Milham said that on one virtual production, there were reflections on a clothing zip that really added to the realism, but such a small detail probably would not have been added in VFX. He also said that the Mandalorian deliberately exploited reflectivity to do some things that looked a bit different from typical VFX-based content. There are also advantages in that you can use real fog and smoke on set. Real props and objects work better in LED volumes because of the real lighting and reflections.

Spaces that don’t work in VR are smaller spaces than the LED volume and bright high key sunlight (like a high noon western)

By chance ROE sent this image of an LED volume in a press release today.

By chance ROE sent this image of an LED volume in a press release today.

Changes in risk and cost

Jelley mentioned that one of the big advantages of virtual production is ‘de-risking’ projects. Costs are reckoned to be about 30% less than traditional content creation. Although virtual sets can be expensive to establish, once you have them, you can rent them out. It is often cheaper to use an expensive VR set than to deal with the costs and complications of travel and physical sets. Jelley said that an independent film, Fireworks, was shot in a week on a VR stage. ‘Big and wide’ shots were shot using simulcam technology (high quality and detailed motion capture then applied to virtual subjects) and then the LED volume used for mid-range and close up shots.

VFX costs don’t go down, the savings are elsewhere. There are also big advantages in working towards sustainability. Although plenty of power is used by LED volumes and the banks of servers, there are big savings in transport and reducing location shooting.

There was little discussion of the LED hardware itself which tells you that the right LEDs mean that there are not any real issues. Milham said that the LED display for the Mandalorian was updated at 24fps to match the capture rate. He also said that the ILM volumes are big, at 18-25k square feet ( 1700m² – 2300m²)

One of the questions was about the use of VR headsets by viewers (rather than by content creators). Sky’s Neil Graham said that he doesn’t expect widespread adoption of this for a long time, if ever for cinematic content although it was ‘the natural place for gaming’ (BR)