As a new school year rapidly approaches, there’s always a lot of excitement in the air. Part of that exhilaration resides in the fact that August and September are most often the months for christening newly-built schools. It brings up some timely questions, though: Have you ever wondered new technologies are forging their way into newly constructed schools? What new devices will populate these vanguard buildings, these brightly lit structures filled with the promises and potential for the future of our children? Two newly constructed schools are opening for the first time in our own area, both an elementary and a larger K-8 school, so I decided to take a closer look at these questions. I focused my investigation on the K-8 school, because I thought the higher grade levels involved would lend themselves to more sophisticated and broad uses of technology. Let’s take a look.

Teachers getting ready for VR in a newly constructed school.

Beyond the obvious desktop and laptop computers for staff and teachers, classroom screens and projectors, there are no surprises here. Consistent with the rest of the district, every student in middle school is supplied with a personal Apple iPad. Yet in a clear effort to appear forward thinking, a recent press release in our local newspaper also touted the rollout of two makerspaces, a video room (with green screen), four (not one) music rooms, and two virtual-reality labs in the school. Now, don’t get too excited. The first three learning enhancements refer to physical learning spaces, while the last involves shared mobile carts with virtual-reality headgear stored safely away and just a little area carved out of the library space to accommodate periodic student VR experiences. So, no, schools are not primed just yet for dedicated physical space for virtual-reality learning. And VR is not ready for prime time in the classroom, at least not just yet. Why is that so? Let me explain.

Technology is not something that simply slips into a classroom, seamless and unnoticed. Rather, all technology has a footprint; all classroom technology must be ‘managed’, if it is to succeed and scale. As far as VR is concerned, this exciting new technology is not ready for prime time in schools because not all of the management challenges have been sufficiently addressed. If hardware manufacturers, content producers, or integrators want to grow their business in the burgeoning educational VR market, they will need to help schools find ways to accommodate these wretched management challenges or suffer the consequences. The consequences are one-off projects, inability to scale or sustain, and the inevitable dying-on-the-vine. The short technology attention span afforded by educators will not help, either.

To be sure, some of the in-classroom management challenges associated with VR are now evidencing some elegant solutions. For example, the maturation of mobile storage and charging carts now on the market are reducing the problems associated with moving, storing, and charging VR paraphernalia. We are also finding increased development of “app management” solutions that eliminate ‘piecework’ management by teachers in favor of automated installation, removal, and settings management for content.

In schools, carts help with mobility, storage and charging. (Spectrum cart shown)

There remain many in-school management challenges for VR, however, pitfalls that will hinder VR from gaining a firmer foothold in daily instruction. But if the industry can help customers proactively solve some of these problems, the future may be brighter, sooner. These remaining management challenges include:

Improved battery life. The short (and diminishing) life of batteries for smartphones, controllers and other devices remains a daunting challenge in light of the length of the instructional day. Teachers don’t want to deal with it.

Hygienics. Cleansing and disinfecting VR headgear for repeated use remains a headache for most teachers.

Teachers screamed loudly about cleaning 3D glasses five years ago. Is cleaning VR headgear after each use any different?

Wireless infrastructure. Will the school’s infrastructure (both wired and wireless) adequately support VR? Will wi-fi performance elsewhere be affected in the school with the expanded use of VR? Mule-like bandwidth speeds in a school will drop a successful VR initiative dead in its tracks.

Check-in and check-out. Did you know that most damage occurs to any instructional material during the time it is being checked out into the hands of students and returned from the hands of students to its place of storage? In the hurry or excitement of the moment, items are dropped, pinched, tossed, smashed or crammed into place. Solving this problem for teachers will go a long way towards sustaining and scaling VR in educational settings.

Reinforcing/repairing. There’s nothing a teacher hates more than having less than a classroom set of VR headgear because several units are in disrepair. Systems for fixing, patching, repairing or duct-taping impaired VR paraphernalia have a long way to go. The industry can make this problem go away by ensuring that schools always have complete spares on hand, and never purchase just the bare minimum of devices and parts. They can also accompany their rush to the educational market with mature and easily accessible parts/replacement mechanisms, which are currently an afterthought.

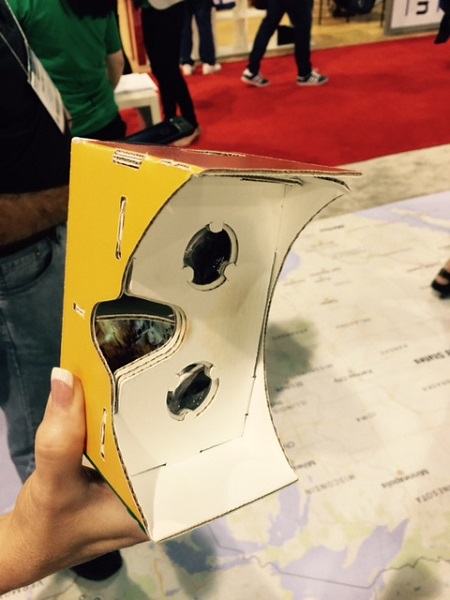

Question: How long will this last in a classroom? Answer: Not very long.

Question: How long will this last in a classroom? Answer: Not very long.

Replacements/upgrades. Schools require a regular and dependable replacement cycle for their VR technologies, even if they say they don’t need one. Their shortsightedness doesn’t have to spell the end of your ongoing revenues, unless you let it.

For these reasons I postulate that VR is not yet ready for prime time in schools. And, no, technology in newly constructed schools, at least in this community, will probably look the same as technology in older construction schools, even though the new buildings are brighter and shinier, with more natural light than legacy buildings.—Len Scrogan