Perhaps the hottest topic and biggest buzz at the Future of Cinema Conference and then at NAB was the debut of the Lytro Cinema Camera. Although we reported on this last week with some more technical details (see http://tinyurl.com/h4r73ap), the first article was written before we had a chance to see the system.

The camera and its capabilities are amazing and truly have the potential to change the way movies are made in the future. The unveiling was not just of the camera, but also a film created with it and an entire ecosystem for light field cinematic capture.

The company gave a presentation on the new camera and described the full tool set for production during the Future of Cinema conference on Sunday afternoon. On Tuesday afternoon, they repeated this presentation but added the screening of the new short film the team made using the camera. This film, produced with a top-notch Hollywood crew, was done to better understand how to work with the camera, to develop the tools for shooting and post production and to learn while doing an actual movie. This project was all done in an astonishing 18 months.

Why will this camera and light field movie making be so revolutionary? Because you can now do anything you want in post production. It is the merging of computer generated 3D images with 3D live action images into a unified virtual world that can be manipulated in ways not possible before. For example, you can change the focus, point of view depth of field, frame rate, color space, shutter angle and more on a per pixel basis. You can even create looks that are not physically possible as was demonstrated by dialing in an f-number of 0.3 so that depth of field was so shallow only a very tiny slice of the image was in focus.

The camera is a beast measuring perhaps 8′ (2.4m) long with a cross section of perhaps 2′ – 3′ (60cm – 90cm) on each side. There are two optical paths. The lower path is a conventional lens and camera solution that allows for viewing the image in a tradition movie-making modality. Images are framed, focused and captured “in-lens” the way the director and cinematographer want. This “look” can be preserved in the final movie or changed in post-production. The light field capture allows a lot more options in post production, however.

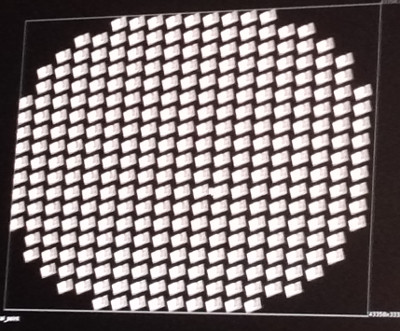

The upper path is the light field capture camera. This contains a main lens which images the screen upon a giant microlens array. Each microlens has a CMOS sensor behind it is essentially a full camera solution that captures a perspective of the scene. There are 46 of these microlens/sensor units at the focal plane allowing 46 different perspectives of the scene to be captured simultaneously. Lytro did not say, but it seem likely that the 755 Mpixels in the Lytro focal plane are made up of a 400 separate aperture images (on the order of 400 FHD images) that are tiled to create this massive array (photo). This massive array can capture data at 300 frames per second with 16 f-stops of dynamic range and a full BT 2020 color gamut.

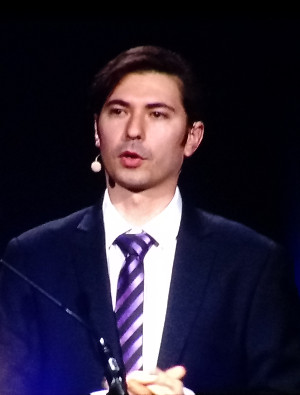

Jon Karafin, who likes to refer to himself as a light field supervisor for his role on the filming, gave the presentation on both days. He started off by explaining the architecture of the light field camera and how this information can now be used to create a 3D volumetric reconstruction of the scene. Karafin thinks this is a new field he calls “computational cinematography.”

Jon Karafin, who likes to refer to himself as a light field supervisor for his role on the filming, gave the presentation on both days. He started off by explaining the architecture of the light field camera and how this information can now be used to create a 3D volumetric reconstruction of the scene. Karafin thinks this is a new field he calls “computational cinematography.”

The light field camera not only captures color and intensity, but it captures the angle at which the light enters the sensor. Complex algorithms can then enable the light at each point in the capture volume to be calculated. A 3D model is then created that is completely analogous to that created with a game engine, except the data points are generated from live actors and objects.

This allows a cornucopia of capabilities that can now be done in post production. For example, the CG and live action worlds are now equivalent so they can be mixed and matched on a pixel by pixel basis. That makes it easy to remove a wall that was captured in the video and replace it with an outdoor scene. This is all done without the use of a blue or green screen.

One can also create depth maps and highly precise rotoscopes that aid greatly in development of special effects and the generation of stereoscopic (or multiview) deliverables. Stereoscopic variables like camera separation and convergence can be controlled in post. Virtual cameras can be rendered in any position in the volume and tracking can be created as needed for story telling purposes. The scene can even be completely relit using virtual lights just as in the CG environment.

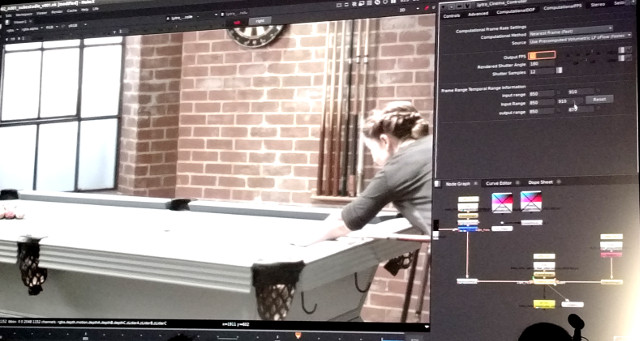

Karafin next did a live demo of some of the post production tools they have developed. These are plug-in for the program Nuke, which is a node-based digital compositing application developed by The Foundry, and used for film and television post-production. These plug-ins allow all the features mentioned above and more to be controlled in an menu driven environment.

The camera does have a set volume based on the main lensing so you have to be careful to understand what is in this volume on-set during capture.

Next, the team screened a short film produced with the camera and post production tools. Called “Life”, it was produced with Academy Award Winners Robert Stromberg, DGA and David Stump, ASC in Association with The Virtual Reality Company. It featured a variety of traditional cinematic techniques and some novel ones as well.

The Nuke demo was running on a powerful workstation, but Lytro also revealed another compelling part of the ecosystem – a cloud-based service. This means all of the data from the camera is uploaded to the cloud and remains there. All editing and compositing are done on low resolution proxies. Once it is time to composite and render in a chosen format, this can all be done in the cloud, exploiting a vast array of processors as needed for the task.

The Lytro Cinema system is now available on a subscription basis, with packages starting at roughly $125,000, which would provide enough processing and storage for roughly 100 shots, according to CEO Jason Rosenthal.

In conclusion, the Lytro cinema camera debut was a watershed moment in cinema history and could very well usher in the start of computational cinematography era. Lytro is not the first ones in this field as Fraunhofer has been developing light field cameras and debuted a short film and Nuke-based tools at last year’s NAB and at the previous IBC. But the Lytro event was an order of magnitude bigger and more impactful and will now firmly establish this technology as a force for the future. – CC