When the Chinese government announced years ago that it was supporting the country’s display manufacturing industry in its 13th Five Year Plan from 2016 to 2020-specifically, to upgrade the manufacturing floor and develop expertise in semiconductor technology and related fields-many Chinese companies responded eagerly to the call.

Working aggressively to expand their capacity in LCD as well as AMOLED, Chinese firms proceeded to build new display production fabs, aided by strong government support and subsidies.

The participating companies included established names and new players alike. The industry stalwarts included the likes of BOE, Tianma, Visionox, ChinaStar, HKC, CEC Panda, CHOT, and Truly. Among the newcomers, meanwhile, were Chongqing Blephone, Chongqing Image Tech, Holitek, AHZ Electronics, Lens Tech, and Trenso.

Changes occurred, however, at the end of 2017. Both the Chinese central government and the country’s state banks started to deploy stricter rules and regulations for business loans. At the same time, lending institutions at the provincial and local levels saw their financing platforms curtailed.

Already, the policies resulting from this time have influenced the financing of several ongoing projects. Moving forward, the policies are likely to continue influencing any plans for expansion by Chinese panel makers-not only for the rest of this year but also even in 2019.

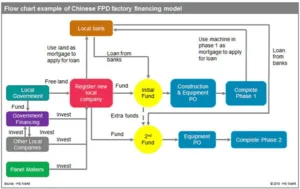

To get a better understanding of how the new regulations influence the ongoing construction and expansion plans of panel makers, it helps to know how a production line used to be funded in China under the previous rules.

Unlike geographically concentrated display production lines in South Korea, production lines in China are more likely to be spread among different locations and funded by local provinces.

To qualify for support from the local government, panel makers must establish a new subsidiary at the location where the fab will be built. Following establishment, both the owner of the new company – in this case, the panel maker – and the local government then invest in the new company, using the invested fund to start construction. Although local provincial-financing platforms are typically used to invest such funds, there remains a big financing gap, given that the construction of display manufacturing fabs require billions of dollars. Here, the gap will usually be filled by bank loans, with the land where construction is taking place offered up by owners as collateral for the loan. This imposes no real hardship on owners, as the land is normally bequeathed by the state to the newly formed company for free.

As shown in the figure, construction starts and equipment is installed following the initial funding. At this point, Phase 1 is accomplished. Display manufacturers then use Phase 1 equipment as the collateral to start a new round of funding as well as to obtain extra subsidies from the government. In turn, the new loan subsidizes Phase 2 of the fab construction.

New rules today

All that changed, however, with the tightening of policy at the end of 2017, as Beijing and China’s state-run banks began deploying new regulations governing loan applications.The new regulations include the following:

- Much tighter control of local land use intended for constructing manufacturing facilities like fabs, so that domestic industries and housing are protected

- Strict limitations on the scope and size of local government financing platforms that previously made loans available to entities such as fabs

- More serious scrutiny of loan applications and less favorable loan conditions, such as higher loan interest rates

- Limits on the total loan amount per year that a bank could provide

More draconian than the previous guidelines, the new regulations are intended to rein in provincial deficits; prevent overheating of the housing-related real estate market; avert systemic risks to the financial sector; and deter investment in older, undesirable industries (such as oil, energy, and steel).

As a result, it is expected that panel makers will receive less funding from local provincial authorities and banks in China. By and large, the pressures of financing a fab in China are now borne by panel makers, which will eventually affect fab construction.

Overall, the impact of the new policies on fab financing will depend on the financial position of the panel maker and the fab in question.

For projects of high-performing panel makers located in big and well-funded cities, financing may not be a big issue, since panel makers and the local provincial government can fill any gaps in financing. However, as the difficulty in financing increases, local governments and panel makers may renegotiate and provide less favorable terms, with the possibility that affected fabs get built slightly behind schedule.

For the new fab projects of less well-funded companies, these may face some difficulties in financing under the new conditions and entail longer delays, even if they remain entirely feasible.

For the new fab projects of third-tier companies or new entrants, whether those lines will be built at all will depend on the disposition of the provincial government involved and the details of each fab. Fabs making use of production lines using smaller glass sizes and old equipment from Samsung Display or LG Display may face more financing challenges, especially in their loan applications.

On the whole, the new business policies will serve to have a dampening effect on fab construction in China, and projects in the early planning phase are likely to be delayed by panel makers until getting funding becomes easier again. – David Hsieh.

David Hsieh is Research & Analysis Director within the IHS Technology Group at IHS Markit. IHS Markit covers the situation and market in its AMOLED and LCD Supply & Demand Equipment Tracker.

This article was originally published on the IHS Markit Technology Blog and is reproduced with permission.