VESA has just announced a new logo programme for gaming displays and video displays that should make life much better for gamers, content creators and consumers and set makers (although not those that may have been less than honest, but who cares about them?)

Over recent year, gaming systems have been able to produce a wider and wider range of different frame rates and from the early days of flat panel displays, when every panel ran at 60fps, panel makers can now support a wide range of refresh rates at up to 360Hz or more. At Display Week, BOE even showed an 8K display that is capable of updating at up to 288 fps – although the engineer who worked on it told me that it had no practical system that could actually drive it! Anyway, VESA has a way for systems to talk to the display to communicate the optimum rate – VESA adaptive sync, but that is just related to the interface. After the success of the VESA DisplayHDR certification programme that looked at the actual display performance, VESA has created two new logos to help buyers recognise that displays are really doing what they claim to be!

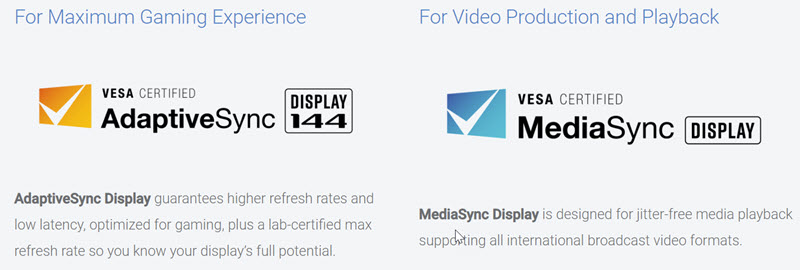

The two logos are for the Adaptive Sync specification which is very comprehensive, and a ‘Media Sync’ logo that covers a subset of the specification and is intended to solve some issues in video.

The key points that are certified are that the video frame rate can support a minimum of 48 to 60 fps for the Media Sync logo and 60-144 fps for the Adaptive Sync logo although that version also allows the maker to put a number on that states the maximum frame rate that the display can go to (and still meet the detailed specification of the test). The Adaptive sync logo also specifies a minimum response time for the display of 5ms. More importantly, it mandates a very stringent and detailed tests for that number that might bring some reality to the claimed specifications.

Frame Rates

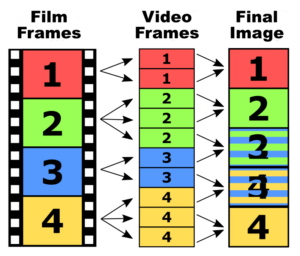

While for anybody that has taken any interest in gaming will understand why you would want a range of frame rates for that, to improve the speed of the display and to eliminate ‘tearing’, it may be less obvious why you would want this for video and media consumption. The big reason is that you can exploit the technology developed for gaming to make the video look better.

Video content can arrive in 24fps, 30 fps, 50 fps (in Europe) and 60fps (and there are other such as Ang Lee that use even wider frame rates, but that is a real niche), and some frame rates that are very close to those numbers, but not quite exact integers. Typically panels have run internally at 60fps so there is often a mis-match. The most well known is probably the famous 3:2 pull down, where if you have 24fps content, you send the first frame for three of the 60 fps periods, and the next frame for two. That gets you to exact multiples, but can cause visible artefacts. Something similar happens in 50 to 60 frame conversion.

Image:Wikimedia Commons (Captions changed)

The Meda Sync logo is tested to ensure that the display can run at an integer multiple of the precise frame rate by covering the key 48-60fps range. So, for example, a 24 fps movie could be run at 48fps which means no need for 3:2 pull down and no artefacts from that process. Of course, support for the variable sync rate has to support VESA adaptive sync. VESA said that the default Movies & TV player in Windows already support Adaptive Sync.

There are ways of changing the frame rate that can cause flicker, so to avoid that, VESA has stipulated a very tough limit for flicker and the display has to work at all the frame rates in the range. Even more tricky, because in gaming the frame rate can vary depending on the GPU load, the display has to be able to cope with any frame rate within the range, within one frame. The test involves completely random and arbitrary frame rates being sent to the display in successive frames as well as ‘ramps’ up and down the range.

Response Times

There is the old saying that there are lies, damned lies and statistics and there is an old display industry addition to that ‘and ANSI lumens ratings for projectors’, but it equally could be ‘and response time ratings for LCDs’. First, different types of LCD, for example, do better or worse on their speed of response to a request from a system to change their brightness. Some go fast on full black to white and slowly on greyscale, while others can change greyscale quickly, but can’t do the extremes very well. Makers, of course, pick what they want to tell you as the response time. Further, if makers tell you grey-to-grey time, they rarely tell you ‘for all greys’, so it has been possible for makers to find which two levels change quickest and quote that. Well, it’s “the” or “a” truth, but certainly not the whole truth.

Many displays use ‘overdrive’ to change grey levels – in other words, they try to get the display to respond quicker by boosting or cutting the signal by more than the desired level to make the transition faster. VESA decided that in itself there is nothing wrong with that, but some have been using overdrive of up to 200% of the desired level and that causes significant artefacts. For this reason, the tests mandate a maximum of +20% overdrive and -15% undershoot.

Just to add fuel to this particular fire, Roland Wooster of Intel, who has been working on this project, told me at Display Week that a difference of 10° Fahrenheit in the temperature of some liquid crystals could halve the response time. So to get ‘an even playing field’ the VESA test protocol includes the following:

- Mandated room temperature of 22.5° to 24.5° C and mandatory warm up times

- Separate test procedures for SDR and HDR as higher brightness usually means more backlight temperature

- The use of a very high speed probe to measure pixel switching speeds (within the range 10% – 90% brightness – going beyond that can lead to measurements being compromised by noise)

- Testing of 20 different grey scale changes with multiple samples of each. The average of those samples has to be less than 5ms to achieve the logo.

The certification only applies to DisplayPort interface, but that includes USB-C and Thunderbolt. In theory, if you use an external HDMI to DisplayPort dongle that supports variable frame rates, you should be able to make that work, or makers could build in the converter and in that way offer the same performance over HDMI, but the VESA logo mandates at least DisplayPort.

All products have to be certified by an independent VESA-qualified testing lab.

There’s a table of the requirements here. VESA also keeps a list of products on its site. At the time of writing there were 8 monitors from LG and one from Dell on the list, but more will be arriving. Older models could be eligible for the logo, but Wooster told us that some would need firmware upgrades to meet the criteria.

The full 71 page test process was available for download here when we went to press.

Analyst Comment

I welcome this development. VESA has done a good job with the DisplayHDR certification and enabled consumers to clearly see what they are getting for their money. Dissolving some of the hype around speeds is a good initiative for the industry and consumer alike. The organisation seems to have done a thorough job on catching behaviour by brands that might distort the value of the logo.

However, it is often said about things described as ‘idiot-proof’ is ‘don’t underestimate the ingenuity of idiots’. The same might be said of vendors that bend specifications and standards to their liking. My guess is that someone, somewhere will find a way to defeat the intentions of VESA and at some day in the future, there will be a V1.1. But that wouldn’t stop me trusting the logo for now. (BR)

Note the article was slightly changed after publication to clarify that only the Adaptive Sync logo mandates a 5ms response and to clarify that there are different levels for maximum overdrive and undershoot. Thanks to VESA for the corrections.