On February 10th I attended a half-day Technology Symposium hosted by Snell Advanced Media (SAM) in New York. The Symposium had five speakers, Neil Maycock and David Tasker from SAM (https://s-a-m.com/), Tom Ohanian from Cisco Systems (http://www.cisco.com/), Larry Thorpe from Canon (http://www.canon.com/) and Scott Rothenberg from NEP (http://www.nepinc.com/).

While Larry Thorpe talked mostly about cameras for HDR and WCG cinema and TV content, four of the five speakers focused on the migration of video from dedicated video SDI networks to more flexible and lower cost IP networks. They were not talking about streaming compressed video over the public Internet to consumers. Instead, they were talking about broadcast-quality video transfers in real time in the production, post-production and broadcast environments, especially in live productions. For example, the transfer of live video from multiple cameras at a sporting event to the broadcast truck and then transfer to various pieces of hardware within the broadcast truck.

Currently this technology niche is dominated by video specific formats and cable technologies. Various flavors of the Serial Digital Interface (SDI) are the major technology in this realm. Short distances (e.g. inside the truck) go by copper-based coaxial cables and for longer distances fiber cable is used. HDMI is also used for the “Last Metre” from a video source to a video display. Except for loop-through displays, HDMI to a display is a dead end. If the content is going someplace where it will be used again such as a switcher or storage, it mostly goes by SDI.

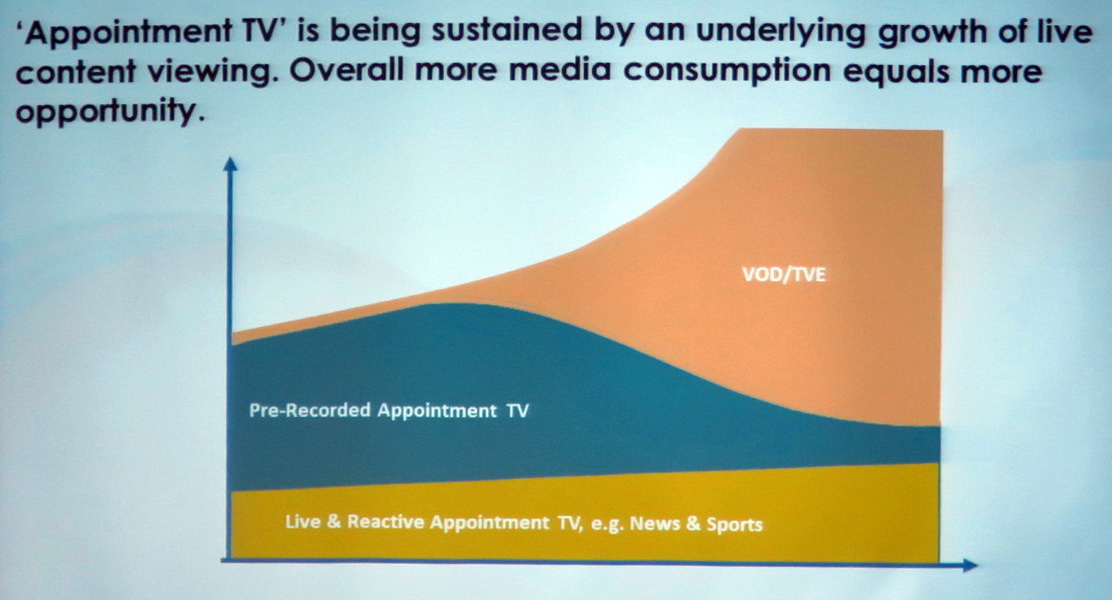

The TV market is changing, everyone agrees on that. In fact, the use of file-based workflows at production and post production has actually reduced the need for real-time, broadcast-quality video transfer in production, post-production and broadcast. Despite this change, Maycock presented the above figure and said there is an underlying but growing base of live events such as sports and news that require real-time transfers and will continue to have this requirement for the foreseeable future.

The problem with SDI compared to IP is also fundamental to its advantages: it is a dedicated video technology. As such, it does a very good job of transferring uncompressed video in real time from one piece of hardware to another. The problem, however, is that the video transfer market is tiny compared to more general IP data transfer market. This low volume drives up prices and retards progress, particularly in data transfer speed.

Click for a higher resolution image

Click for a higher resolution image

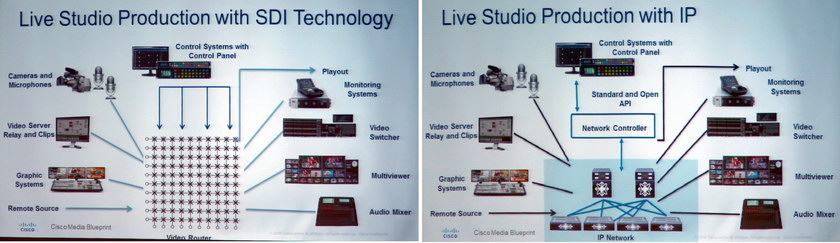

In theory, switching from SDI to IP is relatively simple, as shown by the pair of slides presented by Ohanian from Cisco, a major player in the IP space and a company with a vested interest in VIP compared to SDI. Simply pull your N x M SDI switcher and replace it with a network controller and an IP network. Done!

Well, not quite. Even Ohanian admits there are serious challenges to pure-IP solutions. Four challenges he identified were (with my comments in parentheses):

- The need for unchanged operator workflow (Retraining is really, really expensive! And operator errors in live TV are not acceptable.)

- Low latency and zero packet loss (All VIP projects to date use private networks, reducing the problem, but there are still issues with switching on frame vs. packet boundaries.)

- Precision timing (Same comment)

- Security and redundancy (Every network, including a private one, is subject to hacking because they are all connected at some point to the outside world.)

One problem Ohanian didn’t discuss was the question of proprietary VIP standards. Maybe you have a VIP camera, a VIP storage system and a VIP multiviewer, but if they come from different companies, they may not be able to talk to each other.

Also, live production companies have huge inventories of equipment, including cameras, video servers, graphic systems, monitoring systems, multiviewers and audio mixers designed to work with SDI inputs and outputs but not with real-time IP video connections of any sort. Of course, virtually all of these systems have Ethernet ports and use IP technology for control. Generally, these IP connections are not capable of handling real-time video. Some hardware that accepts VIP actually have two Ethernet ports: one for video and one for control. To use these SDI-based legacy systems on an IP-centric network requires a SDI – VIP converter at each node.

4K UHD video represents a special challenge to everyone, but an opportunity for the IP camp. Currently there are three solutions for real-time 4K UHD:

- Quad HD-SDI (four HD-SDI cables in parallel, each carrying ¼ of the image)

- 12G-SDI

- IP transfer

Although data rates needed for 4K UHD video are 2x – 4x the data rates of HD, these data rates are well within the capability of private IP networks and switchers. Since there isn’t a large inventory of SDI-only 4K UHD equipment, implementing VIP should be easier – new 4K UHD equipment is needed anyway.

David Tasker of SAM addressed the question of “SDI to IP in live production – Why now?” He said the drivers include:

- Need for greater efficiency at every touch point

- Network bandwidth has increased

- 10Gb/s & 25Gb/s Ethernet is here with standards through 250Gb/s

- Emergence of UHD 4K and 8K requires new connectivity standards

- The IT industry offers an attractive and rapid technological development trajectory

- New and open industry standards for VIP have emerged that are eroding closed, proprietary schemes, spawning interoperability

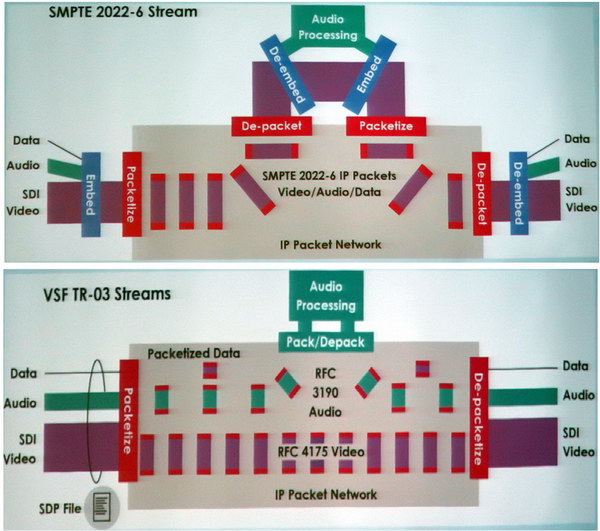

These open industry standards have problems of their own. The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) is working on its SMPTE 2022 suite of standards and the Video Services Foundation has developed TR-03. Both standards come from key industry standardizing bodies and the two have significant differences, especially in terms of how they handle audio and ancillary data.

In SMPTE 2022, the audio and data are embedded in the same packets that contain the video. The advantage of this scheme is it ensures the video and audio get to the destination at the same time, minimizing lip-sync problems. (Nothing can make all lip-sync problems go away!) On the other hand, any processing of the audio or data requires stopping the entire stream, de-embedding the audio and data, doing the processing and re-embedding the audio and data.

In VSF TR-03, the video, audio and data travel in separate packets. This simplifies the audio processing issues, but makes it possible for the audio and video data to get separated. It also allows access to the data, which can be metadata needed to properly direct video to its destination.

Tasker explained how SAM addresses the lip-sync problem and other problems associated with VIP with a technology called “Biometric Signatures.” These biometric signatures are very simple algorithms that identify every frame of video based on its content. He said the technology is very robust and the ability to identify frames survives format conversion, pixel count changes, aspect ratio changes, compression/decompression cycles and the insertion of keyed graphics such as network or TV station logos. Just embed the biometric signature of the associated video frame in the audio packet and, almost regardless what is done with the video, the audio can be re-associated with the video correctly. Of course, Tasker said the Snell biometric signatures have uses far beyond lip-sync, but it is a technology that can ensure correct lip sync even with TR-03 formatted signals.

Both Maycock of Snell and Rothenberg from NEP gave examples of the real application of IP video. Maycock described an experiment done by SAM to show the use of IP protocols to generate “channel-in-a-box” TV channels, all done with pure IP and no dedicated video hardware. They set up a three channel system in an IP hardware platform and got it operating correctly. The experiment came when they used pure software to set up a fourth channel running on the same hardware platform. Maycock said the system was operating in minutes, without disrupting the three original channels.

The system Rothenberg described was more real-life. NEP is best known for its video trucks for sports and other live production on location. In the Netherlands, NEP doesn’t just supply the trucks, it will supply everything from the cameras and camera operators through the directors and announcers to the final production of the broadcast quality video. For example, if a school wants to broadcast a key soccer match against a major rival, just call NEP and they’ll do it for you. The control room can remain in the NEP headquarters in the Netherlands and all that goes to the site is the cameras and cameramen, plus the hardware to get the real-time video feeds to the central control room. This setup is far less expensive than sending a whole crew to the location. The savings in travel and hotel bills alone are big. On the other hand, the risks of the IP links failing are significant. For a small school, losing a game broadcast is a major disappointment but not a catastrophe so this risk may be acceptable, given the lower, more affordable cost. For the Superbowl or the Olympics, however, no avoidable risk is acceptable and the networks pay not only for on-site production but for multiple and duplicate facilities for back-up.

The general take-away I got from this Technology Symposium is that real time video over IP is not only coming, it is inevitable. But not this year, especially not for high-priority projects. Probably, in fact, not next year, either. But within the next couple years, it will start to be a legitimate choice compared to SDI. –Matthew Brennesholtz

Analyst Comment

At the recent ISE show, I moderated a panel on the Aptovision VIP technology. This allows the use of standard 10Gbps switches for uncompressed FullHD. One of the key points made was that these switches costs $100 per port, with prices falling, while dedicated matrix switchers start at $500 and more. Even makers of dedicated switches are seeing the writing on the wall and introducing products that support VIP. (BR)