Some six weeks ago, I wrote an article for Display Daily (Are LED Backlights Dangerous?) about the issues of the impact of blue light, especially from LED light sources, on the health of users. There were some interesting comments to the story from readers, including a good question about the levels of blue light that the TÜV Rheinland is testing for.

I had a look around the TÜV website, but, apart from a press release that mentions that the certificate had been awarded, there was no information. We contacted the organisation about the question*, but hadn’t got a response at press time. It’s strange, it seems to me, to have a certification that a consumer cannot check, to find out what it stands for.

On the same topic, a week or so ago, Apple announced its new 9.7″ iPad Pro and the firm said that it uses the “Night Shift” feature in iOS 9.3 which uses the clock and geolocation to reduce the level of blue light and which I mentioned in my last article. Naturally, display quality maven, Ray Soneira, looked in detail at the Night Shift mode. Ray went back into the recent research on melatonin production and the effect of the blue light and posted an article on his website that looked at this topic.

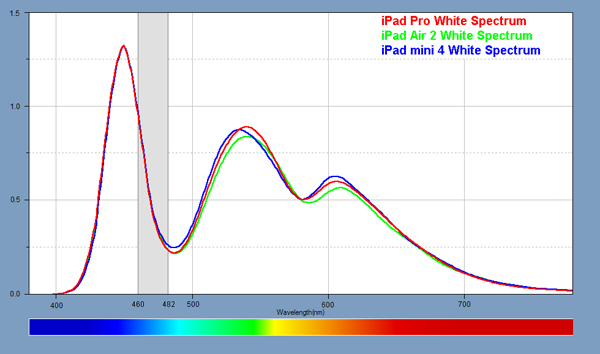

Ray made the point that the spectrum of the blue light that causes problems for sleep cycles represents a significant proportion of the energy in the blue region that is emitted by the iPad. Further, the proportion of that particular blue is higher than in the solar spectrum, which is why backlights can interfere with sleep. If you simply filter all the blue light out of the backlight by enough to materially affect the important range of wavelengths, the image would have a significant yellow cast (as the balance shifts more to red and green).

Copyright © 1990-2016 by DisplayMate® Technologies Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Copyright © 1990-2016 by DisplayMate® Technologies Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Ray points out that most backlights are made by using a blue LED and a yellow phosphor to create a very broad spectrum white. He also suggests that Quantum Dots (QDs) could be used to tune the colour output to minimise the level of blue that is significant in melatonin production.

Now, that’s a good idea, but up to now, QD materials have typically been used to generate the red and yellow light from a blue LED. The blue light comes from the blue LED, not the phosphor or QD. Typical blue LEDs have a peak emission around the same range as the problem area, so, clearly, the LED would need to be specifically tuned to optimise the precise blue – and that could have a cost and efficiency impact as LEDs, as produced, have a range of different colours. An advantage of using QDs is that the light in red and green is very finely tuned, so there would be little crosstalk into the blue.

A number of companies have announced monitors over recent years that have reduced levels of blue and Eizo even has a software application, Screen Manager Pro, that can change the level of blue in the image over time to try to match sleep cycles. However, in all the material I have seen on the topic, only one company was looking to shift the colour of the blue, rather than simply reducing it, and changing the white point.

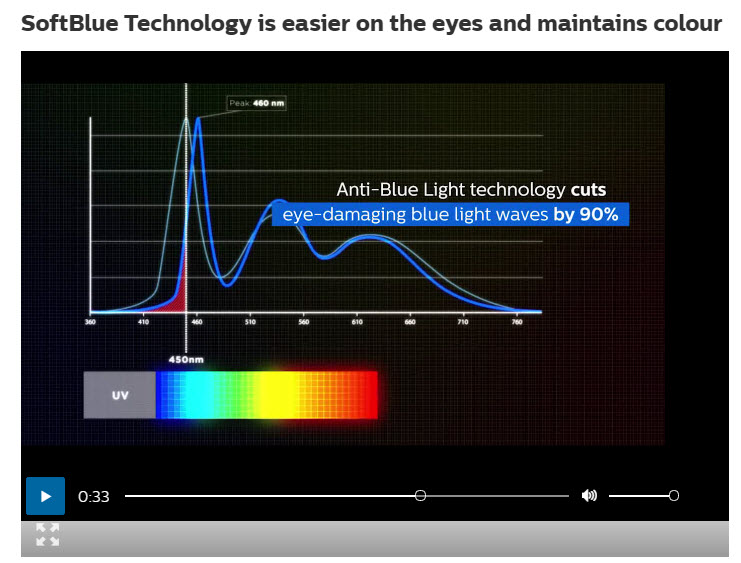

Ray’s article points out that the wavelengths that may be implicated in melatonin disruption are in the range of 460-482nm, but in the advertising for its “SoftBlue”, Philips shifts the peak energy point of the blue from 450nm up to 460nm.

If the research that Ray refers to is accurate, it would seem that the Philips monitor is making things worse in terms of sleep! – Bob Raikes

* TÜV also reported that its 2PfG certification is a “standard” although I referred to it in my original article as a ‘certification’. Now, the whole question of “what is a standard?” is a fraught one, but I learned very clearly and very early on in my career as an editor that the word is not to be used without thought. I used it casually about a “certification” and was taken to task by someone from a big company that was very involved in a genuine “Standards Development Organisation” (SDO) who pointed out that a huge amount of (often tedious and painstaking) work goes into developing genuine standards and that a key point about genuine standards is that they should be open to input. Since then, I have always tried to only use the word in that way!