Ultra-High Definition (UHD) TV has more than just more pixels. I see it as a four-legged stool, with more pixels as one leg, wide color gamut (WCG) as a second, high dynamic range (HDR) as the third and high frame rate (HFR) as the fourth. Recently, I’ve written Display Daily articles on wide color gamut and high dynamic range while everybody has written articles on higher pixel count.

In this Display Daily, I’d like to comment on high frame rate. This is the least well known and least advertised aspect of the upcoming “Better Pixels” technologies. It is also, perhaps, the furthest from widespread availability to cinema and TV viewers.

One issue HFR faces is a nomenclature problem. To someone from Hollywood or elsewhere in the film world, HFR means any frame rate greater than the current 24Hz. The 24Hz frame rate was chosen by Hollywood in the late 1920s with the introduction of sound movies. Before that, silent movies were shown at anywhere from 16Hz to 26Hz, depending. Depending on what, you ask? Well, how the projectionist felt that day, among other things. The camera frame rate would also change within a single film, depending on how fast the cameraman cranked the camera. Humans are much more sensitive to changes in pitch in the sound than changes in motion rendition, which is why a standardized frame rate was needed for the Talkies.

Even at the time, it was recognized that 24Hz really wasn’t good enough. Thomas Edison, one of the key pioneers of the film industry, said that 46 frames per second (FPS) was the minimum needed by the visual cortex: “Anything less will strain the eye.” Edison, however, did not follow his own advice even in his own studio, in part because the large amount of film needed for a 46 FPS film. Another issue was exposure time – film from Edison’s time was much slower than the Red Epic 5K cameras used to make the Hobbit Trilogy. The longer exposure time of a 24Hz camera was better a hundred years ago than the shorter exposure time of a 46Hz camera.

The HFR version of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey in 2012 allowed 3D viewers to see more detail in action scenes

The HFR version of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey in 2012 allowed 3D viewers to see more detail in action scenes

The first modern HFR movie was Peter Jackson’s first Hobbit movie in 2012. Unfortunately, it was only shown in HFR in 3D: a 2D HFR version was not an option for consumers. The HFR version was widely panned, especially by cinema aficionados. It looked too much like video and too little like the cinema was a widely heard comment. Unfortunately, since it was available only in 3D, it is hard to tell if the real objection was the 3D, the low brightness and therefore low dynamic range or the high frame rate. Since the human eye is less sensitive to flicker and other temporal artifacts at low image brightness, the Hobbit 3D HFR wasn’t really a fair test of the commercial viability of HFR in the cinema. Maybe if the Hobbit 3D HFR were shown at 14 Foot Lamberts on a 6P laser projector…

HFR means something completely different in video, where 60Hz and 50Hz content has been the standard since the post-WWII introduction of commercial TV. In the television world, HFR means not 48Hz but 120 or 240Hz content. Unfortunately, the introduction of the additional pixels in UHD content has led to a step backwards in terms of frame rate – UHD resolution content is normally produced at a 30Hz frame rate because of bandwidth issues both for the content creators and the broadcasters.

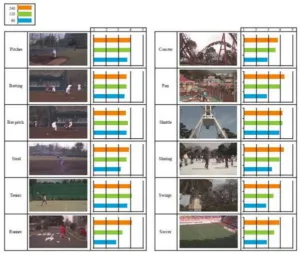

HFR Image quality improvement, as reported in 2009 by M. Emoto and M. Sugawara

There is a significant amount of data showing that even 60Hz isn’t fast enough, even though it is 2½x the frame rate of normal cinema and faster even than the 48Hz of HFR cinema content. For example, Masaki Emoto and Masayuki Sugawara gave a paper at IDW in 2009 showing the results of viewing tests of the similar content at 60Hz, 120Hz and 240Hz that showed significant viewer preference for frame rates in sports and other motion-intensive content. Other data shows the higher the spatial resolution, the higher the frame rate needed in order to appreciate that resolution.

For anyone who wants a deeper understanding of the human factors involved in HFR, WCG and HDR, I recommend spending the 56 minutes it takes to watch Mark Schubin discuss these issues in his YouTube video from SID 2014, also posted on his website, http://www.schubincafe.com.

If higher resolution demands higher frame rates, why haven’t consumers demanded higher frame rates from television and the cinema? Part of the issue is what the consumer and even technical journalists like myself have seen. I have not seen a demo of 4K or UHD content side-by-side with itself at multiple frame rates, although I understand such demos have been given. Most of the UHD demo content I’ve seen is little better than still images and has so little motion in it there is no need for HFR. Gorgeous scenes of the Grand Canyon, a small village in Italy or pretty girls on the beach in the Bahamas. However, this isn’t what people watch in the movies or on TV. Car chases, fight scenes, high speed sports action and other action-filled content form a large part of what people actually watch in the movies or on television. They don’t call them motion pictures for nothing.

There are a (few) modest signs that content creators and broadcasters are beginning to appreciate HFR. For example, NHK showed an 8K, 120Hz HFR display at IBC 2014. At least one decoder, from Korusys, capable of supporting UHD content at 60Hz was introduced at IBC. This H.265 HEVC decoder targets professional applications, but you have to start somewhere, I suppose.

Still, 60Hz UHD and 48Hz cinema aren’t really “HFR.” Dr Jenny Read, a Reader in Vision Science at Newcastle University, contends that a 48Hz frame rate is still not high enough. “We’ve heard a lot about 48hz in recent years – so called high frame rates – but really it’s [a] less-low-frame rate.” –Matthew Brennesholtz