Can virtual reality actually make a difference in the educational endeavor or is it all ballyhoo and exaggeration? That’s a question I asked in my previous article, “Flying High with Educational VR”. Recently I discovered another clear exemplar of how VR can actually deliver on meaningful educational goals. It’s another story worth telling.

This fall, Dana Judd (PT,DPT, PhD), assistant professor with the Physical Therapy (PT) program at the University of Colorado and Brian Kelly, a Simulation Education Specialist for the Center for Advancing Professional Excellence, offered an insightful presentation at our annual university fall technology conference. The session, entitled “Virtual Reality in Physical Therapy Education” explored how Judd’s team is using VR in an educational context. According to Dr. Judd,

“To date [VR] has not been used in PT training or PT education, but has been used with patients.”

Their current project focuses on training physical therapy students in patient movement analysis, a vital part of their patient examination scheme. Citing LD Hedman et al (2018), Dr. Judd emphasized that “examining movement systems, as well as diagnosing and treating movement dysfunction, are critical components PT practice.”

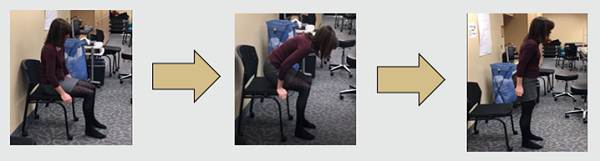

Observing “sit-to-stand” movement in physical therapy.

Observing “sit-to-stand” movement in physical therapy.

Judd and the CU team began by purchasing a virtual environment from CG Trader, a 3D modeling site. She explains: “Once animations and environment were complete, they were imported into the Unity3D game engine. And once all of the assets were in place, the module was then uploaded and hosted by SteamVR.”

To support their hunch that PT training and education could be well supported by virtual reality simulations, Judd created three virtual patients in a virtual PT clinic, with each animation exhibiting common “sit-to-stand” movement errors. Each PT movement animation lasts for approximately 30 seconds, “allowing the virtual patient to perform the sit-to-stand movement anywhere between 5-8 times.” Each animation was also programmed with consistent movement presentations to decrease variability and complexity for the novice learner. Each animation was available to students in distinct virtual layers: fully clothed humans, undressed humans, and (cut-away) muscle animations.

With the simulations in place, Judd would now take aim at testing the use of these VR modules for PT students to practice their movement examination skills. Illustrating how VR is used in their instruction, Judd says: “PT students are asked to verbalize aloud their observations of the movement being studied and are asked questions about muscle performance” and follow-up recommendations.

The VR sit-to-stand simulation, female subject fully clothed.

The VR sit-to-stand simulation, female subject fully clothed.

In their initial study of VR-based PT education, 15 first-year PT students thoroughly tested the approach. Typically, first-year PT students will practice on peers, family, and friends, with limited access to actual standardized patients. To be successful, explains Judd, “novice students require ample deliberate practice to acquire the needed skills; and they need to practice in a safe environment, without variability.” At our CU conference event, I tried out the VR simulations for myself; they were clearly focused on the learning, detailed in every way, and compelling due to the immersion factor.

Perhaps the best way to conceptualize the effective use of VR in any instruction in general, and this physical therapy education in specific, is to overlay a number of important categories for a solid return on investment. Here’s what I saw happening:

Learning Efficiency. Given the iterations of learning possible, students are likely to achieve desired competency levels faster than in the past, and without the expected fatigue common with standardized patients.

Cost Avoidance. Given the costs of simulation devices and reserving standardized patients for student practice, VR is likely to be significantly more cost effective.

Accelerating Learning. Clearly, first-year students are getting more diagnostic experience earlier than they ever have. They don’t have to wait years to get to the fun stuff, the practical skills.

Teaching Efficiency. Scheduling VR instances is likely to be far less time consuming than the current practice of scheduling standardized patients and friends/family/peers.

Increased Capacity. VR systems are likely to allow clinical professors to accommodate/reach more students given the restrictive schedules currently in place.

Although it’s still early on in this project, several conclusions are evidenced by Dr. Judd:

- Using VR to practice movement analysis is received favorably by students

- An immersive VR environment provides a reliable and viable space to practice clinical examination skills

- VR should not entirely replace traditional face-to-face lab or simulation opportunities

In this case, the University of Colorado Physical Therapy Program provides another clear example of the return-on-investment possible with the use of virtual reality, putting real wind behind the sails of VR in education, advancing well beyond the typical marketing bluster of our day. –Len Scrogan