On June 21st, I attended the press preview of “The Art of VR.” This exhibition, whose public dates were June 22 & 23, was hosted by Sotheby’s in New York and was presented by the VR Society. Attending as a member of the public would have cost you $75 for one day or $125 for both days, with discounts for students and senior citizens.

In addition to the approximately 50 Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) exhibitions and demonstrations, there were 24 talks presented over the two days on the industry and the art.

The exhibit occupied two floors of the Sotheby’s building and during the press preview not all exhibitors were fully set-up. Enough were open for business to get a flavor of the wide variety of content encompassed by the title “The Art of VR.” None of the exhibits were intended to showcase VR technology and all used commercially available VR headsets, mostly from Oculus and HTC.

One of the first people I visited was Zenka, who was also one of the few people at the show with AR rather than VR. When you had an iPhone, iPad or Android device with the “Zenk AR Prints” app installed and pointed your device at one of her prints, you saw an AR addition to the physical print on your screen. Not surprisingly, her business card showed a pen and ink sketch of her and when you pointed your device at it you saw her holding a dragon.

Zenka and one of her prints that was augmented by a dragon when you pointed your iPad at it. The image from the sketch was repeated on her business card and the dragon can be seen when pointing your device at her card. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

Zenka and one of her prints that was augmented by a dragon when you pointed your iPad at it. The image from the sketch was repeated on her business card and the dragon can be seen when pointing your device at her card. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

A purely abstract artistic VR effort came from Kevin Mack at ShapeSpace VR. He was showing his work “Blortasia” on an HTC Vive HMD. It was an abstract work with hollow, twisting tubes where you could fly down the tubes or through the walls and see the tubes from the outside. You stood still and your motion was controlled by the VR controllers, not you body motion. Head motion or body rotation allowed you to see what was behind, below or above you.

ShapeSpace VR has a somewhat similar work called “Zen Parade” for the Gear VR HMD that was not on display. This need to create two works for two different HMDs is, potentially, a serious problem for VR art. Another abstract VR artwork I tried was from Jane Lafarge Hamill and titled “Wind in the Woods.” This was an abstract painting with a white carpet about 9 feet (3M) square in front of it. When you donned a VR HMD, you could walk into the painting and see it from all directions in full 3D, as long as you stayed within the limits of the carpet. The carpet boundaries were conveniently marked by virtual lines on the virtual floor when you looked down.

Kevin Mack from ShapeSpace VR showed off his abstract VR work “Blortasia.” (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

Kevin Mack from ShapeSpace VR showed off his abstract VR work “Blortasia.” (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

Jennifer Rundell, COO and Co-Founder of Positron, showed off their VR Voyager motion bases designed to provide a “Premium Cinematic VR” experience. I tried one and saw the New York Times 3½ minute VR experience “Take Flight.” These same Voyager motion bases were also used by YM Movies to show their experience “Le Musk.”

Unfortunately, Le Musk was not operating during the press preview so I didn’t get a chance to try it. A second VR experience involving a similar motion base that I did try was “Raising a Rukus” from The Virtual Reality Company (VRC). This motion base was shaped more like a conventional movie seat, complete with cup holder, except that it had a foot rest to keep your feet off the ground, much like the 4DX seat (Subscription required) I had tried last October. This 12 minute VR experience is also available at the two IMAX VR centers. “Raising a Rukus” is also available for Gear VR for home use without the motion base.

Both of the motion base-based experiences I tried used commercial HMDs to provide the images. Unfortunately, the resolution of current commercial HMDs is not up to the quality of the images presented, severely detracting from the experience. The motion on both motion base VR experiences I tried was quite gentle and did a lot to help the experience. I suspect that by matching the motion of the base to the visual experience will do a lot to reduce VR sickness, although both experiences were short enough for this not to be much of a problem.

Meko’s Matt Brennesholtz and another journalist getting a ride in one of Positron’s ten motion bases. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

Meko’s Matt Brennesholtz and another journalist getting a ride in one of Positron’s ten motion bases. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

All of the VR experiences I tried at The Art of VR were 3D VR. On the “Raising a Rukus” ride, I realized one problem of conventional 3D is completely missing from VR 3D: frame violation. In VR with a wide field of view (FOV) HMD, there is no frame around the image and, therefore, frame violation is not possible. This is both good and bad. Good because frame violation can be disturbing to the viewer. Bad in that frame violation most often occurs when 3D objects appear to be close to the viewer. With this limitation removed, most of the VR experiences at the Art of VR involved a lot of objects flying around, like dinosaur bones flying right at your face in “Raising a Rukus.” In-your-face objects can also be disturbing to the viewer.

Monetization of VR

Nine of the approximately 90 AR/VR HMD ceramic masks made by Zenka. Each mask represents a stylized but actual HMD from the first units in the 1960s to the present. Sales of these masks help support her AR art. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

Nine of the approximately 90 AR/VR HMD ceramic masks made by Zenka. Each mask represents a stylized but actual HMD from the first units in the 1960s to the present. Sales of these masks help support her AR art. (Photo: M. Brennesholtz)

One question I asked several people was “How do you expect to monetize VR?” Remember, the exhibitors were primarily content creators and much of the content was artistic in nature and not primarily commercial. Zenka gave the most complete artist’s answer and said she survived off grants, VR/AR consulting projects, sales of her prints and especially sales of her ceramic VR HMD sculpture masks. Kevin Mack at ShapeSpace VR said doctors were investigating his art, including Blortasia, for it’s calming effect on people with depression or post-traumatic stress syndrome. Others were in it primarily for the art and were not too concerned about monetizing their art.

Several exhibits were not consumer in-home VR applications. Instead, they had the expectation that the VR would be supported by ticket sales. At least two of these were essentially ads for movies, Spiderman: Homecoming from Sony Pictures Entertainment and Alien Covenant from 20th Century Fox. Both would be supported not by tickets to the VR Experience but tickets to the movie. Positron was supported by the New York Times VR and VRC supported by the IMax VR experience. For Positron in particular, hardware sales of the Voyager motion base was the expected long-term path to profitability and these hardware sales would be supported by ticket sales by the customer. There were several exhibits targeting museums where the ticket sales of the museum would support the VR, perhaps with an added charge for the VR portions of the exhibit.

One problem with this sort of public, ticket-supported, HMD-based VR is the need for a full time attendant for each person wearing a VR headset. The attendant would help the user put on the headset and earphones, answer questions, and, perhaps most importantly, sanitize the HMD between users. This individual attention from an attendant essentially guarantees high ticket prices for short VR experiences. As I’ve said before about roller coasters, 4D movies and VR, high prices don’t necessarily keep people from experiences they really want, but the ticket prices sometimes limit the widespread availability of the experience. 2D and 3D movies are available virtually everywhere while 4D movies and roller coasters are at a relatively few specific venues world-wide.

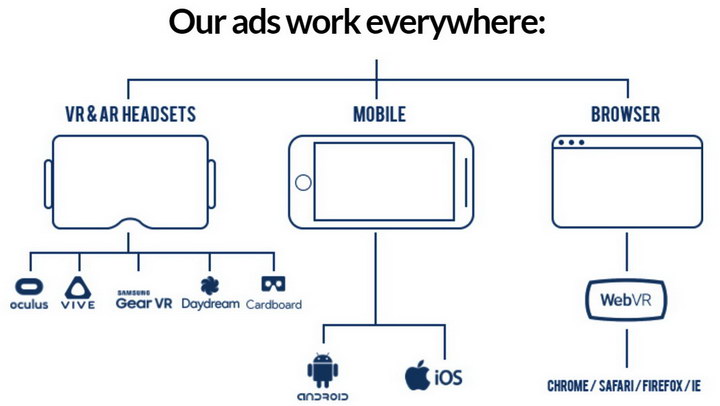

Vire said its VR and AR advertisements work on all consumer VR platforms (Image Vire)

Vire said its VR and AR advertisements work on all consumer VR platforms (Image Vire)

There is one source of funding for VR software no one mentioned. A press release crossed my desk from Vire titled “World’s first VR & AR based cross-platform ads.” You hardly need to read the press release or visit the company website – the press release title tells it all. Is advertising the future of consumer AR and VR? Unfortunately, the answer is probably yes. –Matthew Brennesholtz