For anyone interested in the prospect of better image quality for cinema, television and mobile devices, the April issue of SMPTE’s Motion Imaging Journal is a must-read.

Cover of the April edition of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal (Credit: SMPTE)

Cover of the April edition of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal (Credit: SMPTE)

The seven technical articles, including two on-line and not in the paper journal, cover almost the entire range of issues associated with high-quality images, including 8K, wide color gamut (WCG) and high dynamic range (HDR). The one issue not seriously touched on was high frame rate (HFR). The seven articles were:

- Hitting the Mark—A New Color Difference Metric for HDR and WCG Imagery from Elizabeth Pieri and Jaclyn Pytlarz at Dolby. They discuss how previous color evaluation methods were suitable for SDR but fail in today’s market, especially in the darker scenes used in HDR content. A technique based on the new BT.2100 ICtCp encoding is shown to be more accurate.

- Choosing Encoding Parameters for High-Dynamic Range Streaming by Sean T. McCarthy, also from Dolby, discussed encoding of HDR and WCG content using current standards for streaming applications with the goal of maximizing viewer image quality and minimizing the bit rate.

- Beyond 4K: Can We Actually Tell Stories in Motion Pictures and Television in 8K? was by Pierre Hugues Routhier, a consultant currently working with major studios and broadcasters on production, research, and training related to advanced imaging. It discusses the problems associated with the use of 8K at the display as an entertainment format. I’ll come back to this later.

- Access Services for UHDTV: An Initial Investigation of W3C TTML2 Subtitles (Closed-Captions) was by Simon Thompson and Peter Cherriman at BBC Research. You might assume that closed captions wouldn’t be affected by HDR but everything is affected by HDR. Closed captions are typically shown at 100% screen brightness. This is fine with a 300 cd/m² SDR display but completely unacceptable with a 1500 cd/m² HDR display.

- A Brightness Measure for High Dynamic Range Television was written by Katy C. Noland and Manish Pindoria, both also at BBC Research. The article discusses brightness changes both at scene changes in the content and between the content and advertisements. HDR can make these brightness changes more extreme than in SDR. They discuss first how to evaluate the magnitude of a brightness change and then describe a human perception test that evaluates which brightness changes are not annoying, which are slightly annoying and which are annoying to the 20 subjects, using 60 test images.

- Characterization of Processing Artifacts in High Dynamic Range, Wide Color Gamut Video was written by Olie Baumann and two colleagues at Ericsson and was the first of the on-line only articles. They point out that with conventional ?????? encoding and with the extreme non-linearities of the PQ EOTF system, color processing causes noticeable color and brighness artifacts in certain regions of the WCG/HDR color volume. The authors 1) identify where in the color volume these artifacts occur and 2) suggest color processing kludges to remove them. Unfortunately, they do not analyze the BT.2100 ICtCp encoding scheme which should reduce these artifacts.

- A Newly Developed 8K/HLG Broadcasting Camera System With Three CMOS Image Sensors was written by Tsuyoshi Sakiyama and three of his colleagues at NHK and is the second of the on-line only articles. They discuss NHK’s three-chip 8K camera with 5/4-in. image sensors. The camera supports both high dynamic range and high frame rates, including 59.94, 119.88Hz. They also discus a 9 mm (wide angle) to 720 mm (telephoto) zoom lens designed for the camera. The camera is only slightly larger than a comparison 3-chip 2K camera and has a slightly higher dynamic range than that camera. NHK expects to use the camera for the 2020 Olympics.

Storytelling in the Cinema

Pierre Routhier discusses 8K as an entertainment format for cinema, television and mobile devices. He argues that the 4x extra pixels in an 8K display provide no image quality improvement in standard cinema, television and streaming applications and are entirely wasted. For some viewers, e.g. the ones that like to sit in the rows near the front, in premium large format (PLF) cinemas such as IMax, there will be a little image quality improvement visible. He said that for any display format, including PLF cinema, to take advantage of 8K, significant changes in how cinema and television tell stories must be made. He says IMax has long recognized these problems and in their 1999 15/70 Filmmaker’s Manual they tell cinematographers, “you don’t have the same tools you normally have to enhance emotions, such as close-ups.”

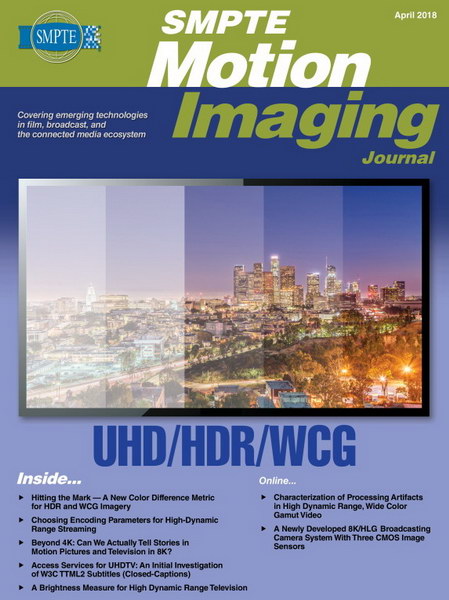

Framing in Motion Pictures. (Credit: P. Routhier)

Framing in Motion Pictures. (Credit: P. Routhier)

Before he started on the problems with 8K, he discussed framing conventions currently used in creating 2K and 4K motion picture content, as shown in the images above. In his Figure 2 he shows a range of images from extreme wide-angle to extreme close-up. His Figure 3 shows how cinematographers use these types of shots. The extreme wide-angle is used to give viewers a sense of the place, the setting of the story being told. The extreme close-ups, most commonly of people’s faces, are used to convey tension (emotion) and how viewers are supposed to feel. These two types of shots often have little or no motion in them. The middle range shots show the action going on and often have a lot of motion in them. In his Figure 4, he says this type of middle-range shot actually occupies the large majority of the movie’s time. As any moviegoer can vouch for, there can be a lot of motion in these middle range shots in modern movies.

Motion Blur

It is not just one problem with 8K, Routhier says, but three separate problems. The first problem he discusses is motion blur in images – much higher frame rates are needed. He doesn’t even consider 24 or 30Hz – he starts his discussion at 60Hz. He uses the Red Weapon VV 8K with a 50mm lens camera tracking a subject 20’ (6.1M) from the camera as an example of a typical mid-range action scene. The Red camera can capture 60Hz at 8K. With this frame rate, the subject must be moving at less than 0.26 km/hour to avoid motion blur. Since the average walking speed of a person is 5km/hour, there can be virtually no motion in the “action” scene if the cinematographer wants to avoid motion blur. At 120 Hz, something the Red camera can only capture at 5K, you can have only 0.5km/hour of motion and avoid motion blur. By this measure even 240Hz isn’t high enough.

Resolution of the Human Visual System (HVS)

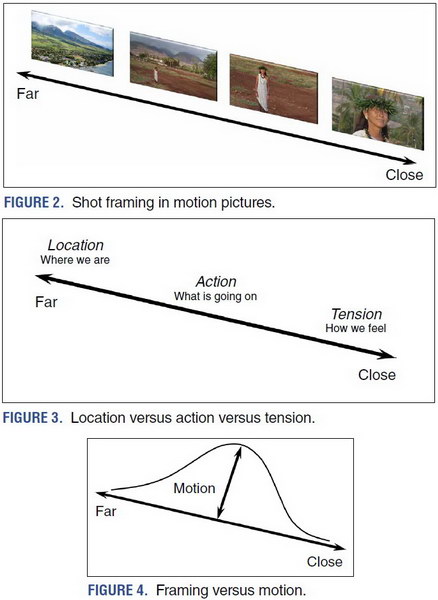

The viewer with 20/20 vision must sit closer than 8’ (2.4M) to a 65” 1920 x 1080 HDTV before he sees the resolution benefits of UHD TV (Credit: P. Routhier)

The viewer with 20/20 vision must sit closer than 8’ (2.4M) to a 65” 1920 x 1080 HDTV before he sees the resolution benefits of UHD TV (Credit: P. Routhier)

The second problem Routhier addresses is the question of the resolution of the HVS and whether pixels will be visible. This, of course, is a well known and well understood problem among display professionals although the marketing departments for 4K and 8K systems have tried their hardest to ignore it. He uses as an example a 65” class (64.5” or 164cm diagonal) 16:9 TV screen. With UHD-1 resolution (3840 pixels, sometimes called 4K), a viewer with 20/20 vision must sit within 3.75’ (114cm) of the screen before the pixels will become visible. It is rare that a TV viewer sits this close but Routhier says some video gamers sit this close to the screen, even a 65” screen. So, for the few gamers that choose to get within 3.75’ of a 65” screen, UHD-2/8K offers some image quality improvements. Now all the gamer needs is a game engine that will drive all 8K pixels at 120Hz or more. Gamers aren’t so concerned about motion blur as they are about the latency in the system and 1/120th of a second latency is better than 1/60th of a second.

For UHD-2 resolution (7680 pixels, sometimes called 8K) the viewer must sit within 13.6” before the pixels become visible. Even gamers don’t sit this close to a 65” screen. However, people buying a TV in a shop or experts at a trade show will come this close even though it does not represent realistic viewing conditions.

When Routhier does a similar calculation for PLF screens, he comes up with a viewing distance to perceive 4K pixels of 52’ (15.8M). Since PLF seats are often at about ½ the screen width, or 35’ (10.7M) in his example, he says some of the audience could perceive 4K pixels and 8K pixels would make the image pixelation invisible.

Aesthetics and Proxemics

The motion blur and, to a lesser extent, the resolution issues associated with 8K resolution merely waste pixels. If the extra pixels were free, and the history of HDTV and 4K suggests that eventually it is likely that 8K pixels will not add much to the display cost, then why not have them? Motion blur? Viewers are accustomed to it and it is part of the “film look” aesthetic. Resolution is similar: you don’t have to sit that close. Of course, then what’s the point of 8K?

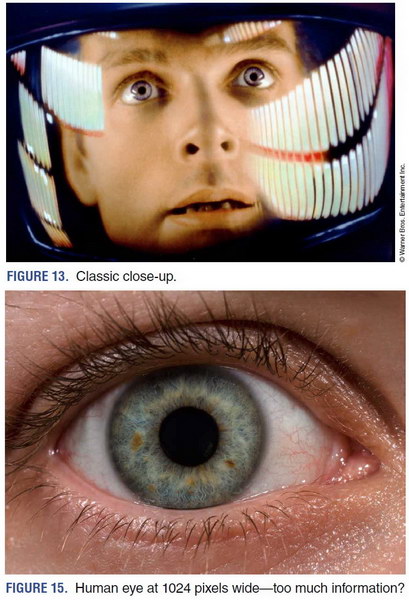

Rendering close-ups in film cinema (top) which has about 2K resolution and 8K. In 8K the eye in the top figure would be about 1024 pixels wide. The lower image shows a different eye with 1024 pixel width. (Credit: P. Routhier and Warner Brothers)

Rendering close-ups in film cinema (top) which has about 2K resolution and 8K. In 8K the eye in the top figure would be about 1024 pixels wide. The lower image shows a different eye with 1024 pixel width. (Credit: P. Routhier and Warner Brothers)

Routhier’s discussion of aesthetics and proxemics shows that 8K pixels are not just neutral but a positive detriment to story telling, especially when viewers sit closer to the screen than 4K pixels would allow. The question of aesthetics has been around for nearly a hundred years. Movie stars have written into their contracts that in close-up scenes, the director will reduce the resolution of the image in order to hide blemishes in their faces. We aren’t talking about disfiguring flaws, but the pores, nearly invisible hairs, microscopic wrinkles, tiny blood vessels and other features we all have, even beautiful movie stars. Movie stars have never wanted to admit they were merely human. Something like this happened with the transition from SDTV to HDTV when some sets had to be rebuilt when the HDTV camera revealed they were built out of wood-grained plywood and not real wood.

This was shown by Routhier in the figures above. The upper one shows a close-up of astronaut David Bowman (played by actor Keir Dullea) in 2001: A Space Odyssey as he dismantles the malicious AI computer HAL 9000. This image filled the screen and, assuming the film resolution was about 2K, made Dullea’s eye about 256 pixels wide. The same image at 8K would make the pupil about 1024 pixels wide. This 2001 closeup is compared to a modern image of an eye 1024 pixels wide. Is it really necessary or desirable to see every blood vessel in the white of his eye?

Proxemics

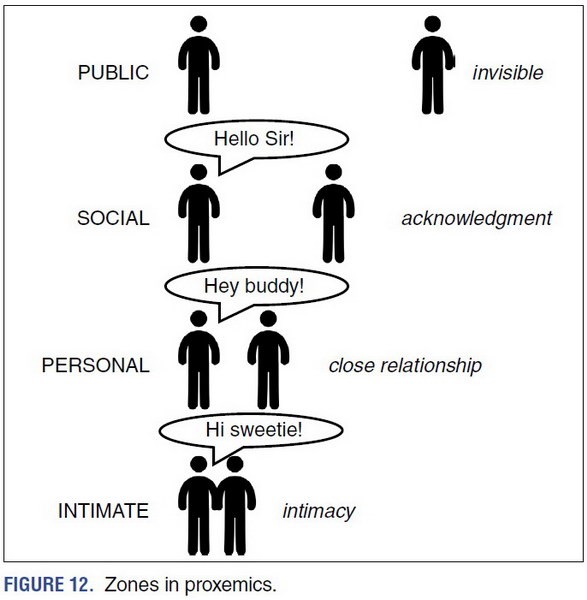

A simplified view of the zones in proxemics. (Credit: P. Routhier)

A simplified view of the zones in proxemics. (Credit: P. Routhier)

Proxemics is the study of “personal space,” or how close we will allow others to approach before we feel uncomfortable with their proximity. If a movie is made for a normal 4K cinema, close-up shots are designed to make you feel, well, close to the subject, in the intimate or near-personal zone. If you show the movie framed this way on an 8K screen and the viewers then sit at 8K instead of 4K distances, the image will appear to be too big and uncomfortably close to the viewer. Of course, you could frame the images to produce the desired sense of intimacy at 8K distances but then you could only show the movie in an 8K theater. Shown on a 4K screen with 4K viewing distances, the director’s desired sense of intimacy is lost. The problem is even worse when the movie is transferred to HD or UHD TV and viewed at normal TV distances.

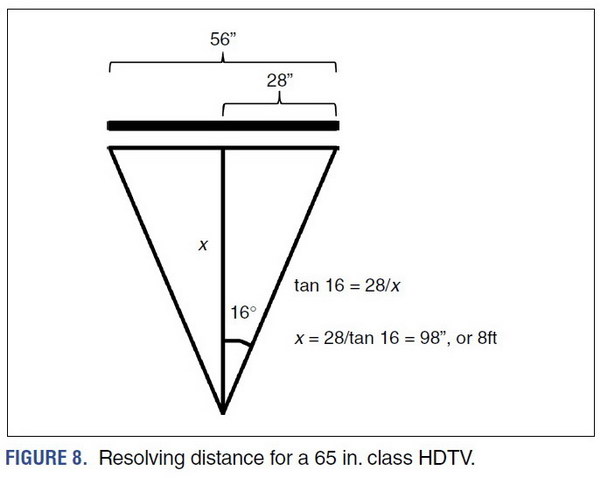

Face size with an 8K image (Credit: P. Routhier)

Continuing the 2001: A Space Odyssey example, Routhier said Dave’s face would need to be the size of the red rectangle in the image above to avoid excessively invading viewer’s personal space when they were sitting at the minimum screen distance for 8K images as determined by resolution. This has problems, however. First, the scene would lose much of its flavor with all the peripheral content around the face. Second, the viewer at that distance has trouble seeing the whole screen and might not even be looking at the face, let alone realize it is the key to the image. In either case, much of the impact of the story told by 2001: A Space Odyssey would be lost.

Getting back to the original question, “Can we tell stories with 8K?” The answer is clearly yes. A skilled storyteller can tell a story in virtually any medium but telling a story is not likely to be easier in 8K than it is in 4K, 2K or analog film. After all, one of the best stories ever told by the cinema, Casablanca, was told in black and white with about 1K resolution and about a 100:1 dynamic range. As IMax recognized in 1999, some of the cinematic storytelling techniques are lost in high-resolution, large screen imaging. No doubt cinematographers would develop new, 8K specific techniques, but would the story be any better? -Matthew Brennesholtz