Although I’m a committed technology geek and I have adopted or taken an interest in many of the new technologies over the years. However, one I really didn’t find compelling although intellectually I could see the importance and that was video conferencing. More than twenty years ago, I gave a talk about ‘The Next Ten Years in Technology’ and I remember saying that “In ten years, Intel will still be telling you that videoconferencing is the ‘next big thing'”. Why?

Well, there were two big factors, I think. One was that the communication infrastructure didn’t exist to deliver good quality video with low latency to many endpoints, although dedicated facilities could support the application. Of course, dedicated facilities do not allow mass roll-outs. “Metcalfe’s Law” says that a network’s value is proportional to the square of the number of nodes in the network, so if video conferencing was going to work in the mainstream, it needed nodes in the tens of millions in a single country. Video cameras were also expensive and the processors needed to support the codecs used quite a lot of power.

However, there was also a bigger problem for me and that was that I found that I simply did not find video conferencing engaging. I was famous in my family for the concentration that I could bring to what scientists called ‘ludic’ reading – that is when you ‘lose yourself’ in a book. If I was deep in a book, I just would not be aware of what was around me. There was a similar situation when I was on the phone, especially to friends. On the other hand, when I used video conferencing systems, not only did I not have that level of focus, but I also found it very easy to be distracted by things around the display. It was almost as if when using the phone, my visual perception was turned right down, but with video conferencing it was turned up but my focus was not retained.

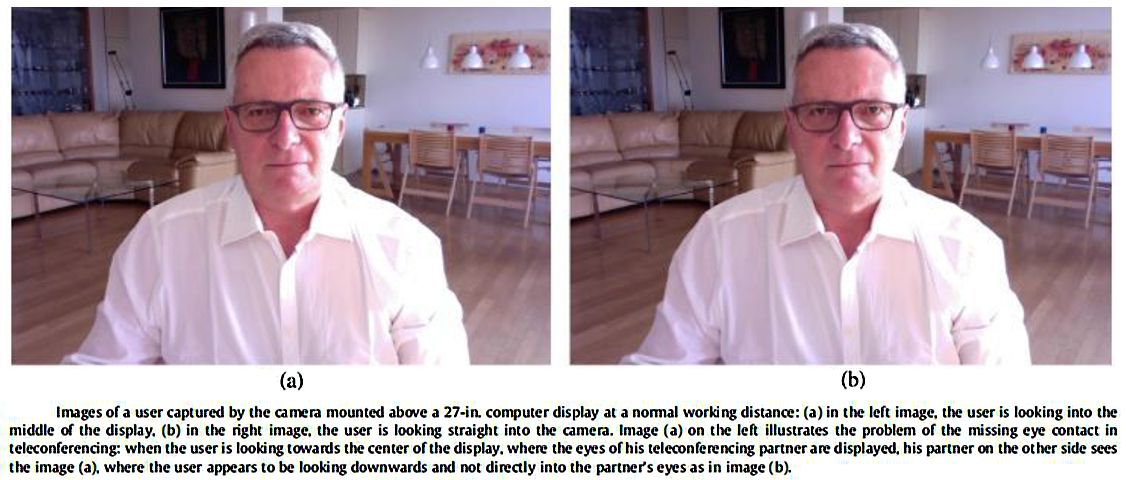

I liked the idea of video conferencing, so thought quite a lot about why it didn’t really work for me. Eventually, I decided that a possible factor in this lack of engagement was the lack of eye contact with the person at the other end. We humans are incredibly good at understanding where those we are talking to are looking. It’s irritating when you are talking to someone and you see them looking slightly over their shoulder for someone more interesting or more profitable to talk to (you could see this quite a lot at trade shows when there were such things!).

So the idea of getting good eye contact seemed an important one in developing the immersive feel of video conferencing, but the camera is placed around the edge of the display, so the eyes of the person you are connecting with are looking away from it.

Various groups saw this issue as a problem and there were various software solutions that could modify the image from a camera to make it look as though there is eye contact. (A New Way to Improve Eye Contact in Video Conferencing Systems, RealD Updates its Intelilight Technology – and More and I’m sure we reported on Intel doing it, although I couldn’t find it in the database!)

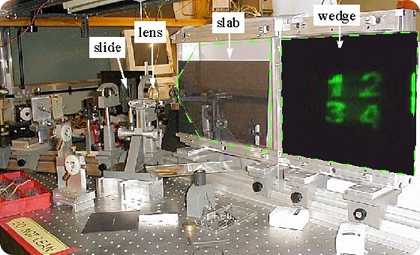

Years ago, I was talking to a scientist that was developing a concept called “The Wedge”, where TIR was used to direct light out of a wedge-shaped waveguide, with an image injected by a projector from the side to make a flat display. We had been monitoring the technology since we first saw it at EID in November 2020 (Display Monitor Vol 7 No 47). Although it was aimed at TV and monitor applications, and we thought it was ‘surprisingly good’, I commented that I thought that the image quality (especially contrast) was not good enough to compete with LCD and PDP.

An Early Wedge Display (https://tinyurl.com/yxuqreep)

An Early Wedge Display (https://tinyurl.com/yxuqreep)

“Presumably, though, the light can go both ways, so you could use it to capture the light into a camera, so that a video conferencing user could maintain eye contact?”, I asked (or words to that effect). The developer dismissed the idea, so I was quite surprised that in 2010 at SID, the Microsoft keynote speaker talked about the concept (still being promoted by the same scientist) being used with a camera (and also being used for steerable displays for 3D).

Anyway, after all that, the smartphone world is trying very hard to put a camera behind the display to get rid of notches and holes. This technology is just beginning to appear in the market and although I haven’t tried the first device on the market from ZTE (What Bob Saw on the Net 21 08 2020), I would expect some measure of compromise in performance. However, if OTI has its way, high end smartphones with OLED displays will not suffer too much. (Materials Remain Important for Under-Display Cameras).

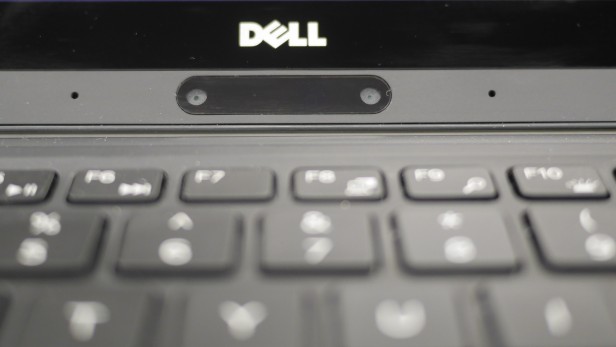

So to, finally, get to my point, the idea of putting the camera under the display is not likely to be limited to smartphones, which suffer less from the lack of eye contact simply because the displays are smaller, so there is a smaller distance between the image and the camera. On notebooks and desktop monitors, the camera is well away from the centre of the display, so there is a more compelling reason to move the camera into the centre of the display. On notebooks, there is a desire to get the camera away from the top of the display. Dell tried moving the camera to the bottom of the display, but found that users really disliked the ‘up the nose’ view that this produced and it had to revise the design. (Dell fixes its XPS 13 webcam, putting it on the top of the screen where it belongs)

Dell’s XPS 13 had a camera at the bottom of the display, but this was unpopular. (Image:Trusted Reviews)

Dell’s XPS 13 had a camera at the bottom of the display, but this was unpopular. (Image:Trusted Reviews)

The pixels on monitors and notebooks are that much bigger than on smartphones, so there should be plenty of glass to get the light through to the camera, but nearly all IT displays are LCD which adds complications. It may be that the initial developments will be in the OLED notebooks that are trying to penetrate the high end of the market. In that part of the market, further reducing the bezel size is also an attractive possibility and there is the possibility of using technology that has already been developed for smartphones.

In conclusion, Covid and widespread access to good broadband has solved one of the barriers to videoconferencing. It looks as though under-display cameras may solve the problem of the degree of immersion in the experience. (BR)