My second article from the HPA Tech Retreat is a little ‘down in the weeds’ of HDR and the talk I’m covering was given by Dr. Charles Poynton, whose book on digital video I read over twenty years ago and an independent expert on colour and video. His topic was ‘a definition of scene-referred’ video.

This is a phrase I came across several years ago, when HLG technology appeared as a method for handling HDR content. It was used to describe how HLG works – by, effectively, surveying the scene and mapping the range between the highest and lowest luminance to the grey levels in the HLG transfer function. The PQ system, in contrast, maps specific grey levels to specific levels of luminance.

This is a phrase I came across several years ago, when HLG technology appeared as a method for handling HDR content. It was used to describe how HLG works – by, effectively, surveying the scene and mapping the range between the highest and lowest luminance to the grey levels in the HLG transfer function. The PQ system, in contrast, maps specific grey levels to specific levels of luminance.

At least, that’s how I understood it, but Poynton disagrees. He explained this in his talk. His purpose to clearly define “Scene-referred” as he regards it as a vital concept in video production and without accurate definitions, things can go astray.

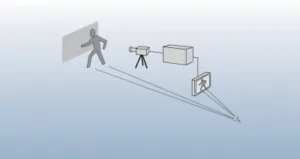

Digital imaging is usually shown by this simple diagram.

He started by explaining that for a lot of content, what you see is not a real scene. He talked about the movie ‘Pleasantville’ which has coloured characters on a monochrome background. Without colour, the movie doesn’t make sense. In that movie, the background was made monochrome in post-production, so there is no mathematical relationship between the original scene and what you see. Further, the difference can’t be described by metadata.

Another example of the way that images are presented that is not based on physics, but is an artistic device. He showed a still frame from ‘Romeo is Bleeding’ that uses the idea of a mask formed by two circles is ‘shorthand’ for ‘viewing by binoculars’. It’s not what you see if you use binoculars.

The finished movie may not even use a camera at all these days, so the first diagram is wrong. Current practice is best shown by this version.

Because of the amount of manipulation between the scene and what the creator sees on the mastering display after post-production, it becomes clear that what is critical is not the ‘scene’, but the master display where the content was viewed. He summarised this with his ‘Axiom Zero (A0)’.

“Faithful (authentic) presentation is achieved in video/HD/UHD/D-cinema when imagery is presented to the consumer in a manner that closely approximates its appearance on the display upon which final creative decisions were approved”

(in searching online for this, I found it in a thesis presented by Poynton as part of his 2018 PhD – available on his website)

Fundamentally, then, the scene is not important, in Poynton’s definition of faithful presentation. He defined a display-referred image as

“Image signal values having a documented mathematical mapping to absolute colorimetric light at the surface of a particular display viewed in a particular standard or specified viewing condition”

He extends that definition to a mastering-display-referred version that references BT.1886 for HD or ST2084 for HDR.

If you annotate the first diagram and add real light levels, which could easily be 100:1 in difference (his suggestion of 32K nits at the scene and 320 nits on a consumer TV), although 1,000:1 is not impossible. Mapping to cinema with diffuse white at 32 nits would meet this 1,000:1 ratio. That affects the way the human brain perceives the image. There are three named effects that change this.

-

Hunt Effect: colourfulness diminishes as overall luminance is reduced

-

Stevens Effect: Contrastiness diminishes as overall luminance is reduced

-

Bartleson/Breneman (surround) effect: for an image displays in a limited viewing angle, colourfulness and contrastiness diminish as the surround is made darker relative to the average luminance of the image

Basically, contrast and colourfulness are very different when seen at high and low levels of brightness. If you just process mathematically from high to low brightness, a daylight image looks like twilight. To make it look like daylight, you have to adjust the contrast and the chroma and it’s not yet a transformation that you can model.

After working a long time on this topic, he defined scene-referred this way:

“Image signal values having a documented mathematical mapping from estimated colorimetric light (e.g. absolute or relative luminance, or tristimuli) in a real or imagined scene to image signal value”

In other words, you should be able to calculate back from the light to the signal. Poynton said that if you look at the OETFs for cameras and the corresponding EOTFs for displays, there is a mis-match – they are not mathematical inverses. That is to compensate for the kinds of perception effects discussed above. What comes out of the camera is not scene-referred, but is display-referred – it’s what looks reasonable on the monitoring display.

Poynton then looked at an ‘absolute scene-referred’ definition which depends on a standard grey at 18% reflectance (or other diffuse reflector). A relative definition is also possible.

HLG is Unclear

While PQ is explicitly ‘display referred’, HLG is not clearly defined as such. In fact, the BBC says that “HLG is scene-referred, like conventional TV”, Poynton said. However, conventional TV has never been scene-referred but has always been display-referred. Further, you can’t bolt scene-referred at one end to display-referred at the other end as this ignores the manipulation between the scene and the display.

Poynton said that it’s reasonable to have an HLG curve in the camera, but that doesn’t make it scene-referred. It may also be sensible to have HLG at the back end, but that introduces questions about rendering.

Analyst Comments

Defining terms often seems like a dry and academic exercise, but as the Chinese saying “The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their right names”. If you ever get into market analysis and market research, be prepared for plenty of time spent defining your terms – at least that’s true if you do it properly! (BR)