I reported last week (Plenty to See from Technicolor in Rennes) on my visit to the Technicolor R&D Department in Rennes. The last item on the visit was on a topic that has intrigued me for some time and was one of the main reasons why I would have liked to have spent more time. My interest in lightfield cameras was really fired by what I saw from the Fraunhofer IIS at the IBC show in 2014 and was the most interesting glimpse of the future that I saw there.

One of the limitations of conventional photography (and displays) is that the technology is all about capturing an image that shows what is seen from a single point. That, of course, allows photographers to have complete control of what is seen, but capturing a flat image from one direction means little flexibility if a different artistic decision is made about an image.

For example, during my visit to Technicolor, one of the images I took very quickly. Unfortunately, I had forgotten that to try to capture a previous image, I had set my camera to manual focus, while it is normally set for auto focus. As a result, the image I took was out of focus and there was nothing I could do in post processing that could make it good enough for use.

A different approach to photography is to try to capture light from many different directions at the same time. There are special cameras that do this, such as the original one from Lytro (that we have been reporting on since 2011) and others from companies such as Raytrix (which has a nice section on its site about the limitations of the concept). Pelican Imaging is doing similar things for smartphones and Apple bought LinX, which is also working on multiple camera arrays. These, among other things, allow the capture of still images that afterwards can be manipulated to change the focal point and aperture etc.

At IBC, I interviewed Frederik Zilly of the Fraunhofer IIS about a virtual video camera array that he was showing at the event. His group was working on the idea of capturing content with multiple cameras (his system used a 5 x 3 array) and this has the potential to allow the changing of camera types, position, focus and field of view after capture. To me, this was really a potential enabler of 3D because it allows 2D and 3D final content to be created from the same capture, without compromise, as the camera settings can be independently chosen.

Chris wrote an article for our subscribers last year about the development and the Fraunhofer released a test movie Coming Home from the Fraunhofer showing the results from the system.

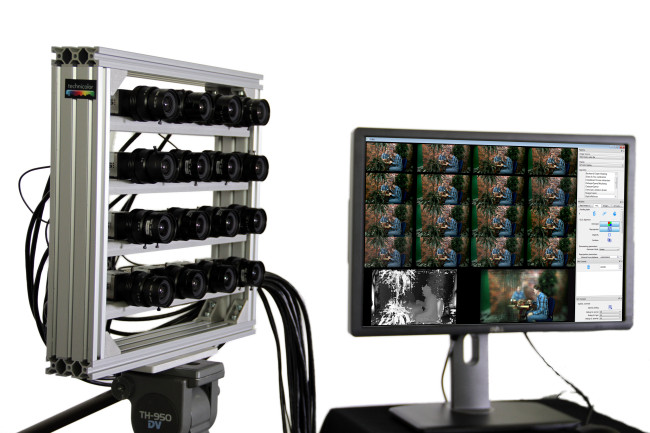

Technicolor is very interested in this area and in Rennes, we had a look at content that had been captured by a 4 x 4 camera array

Lightfield rig screen at Technicolor – Click for higher resolution

Lightfield rig screen at Technicolor – Click for higher resolution

Technicolor, as you can imagine, sees great potential for the use of light field cameras in the development of content for VR & AR applications. However, there are big challenges in how to store, compress and manipulate the huge amounts of data that are required. Another challenge is dealing with the computation load of combining the images and allowing, for example, real time re-focusing of content – a demonstration that we saw at the research centre in Rennes. That is likely to keep the team busy for a while! The demonstration we saw was not “production quality”, but we are still at the start of this technology, although after our visit, our team saw the new Lytro Cinema lightfield projector at NAB and that is a real product. (Lytro Wows with Cinema Light field Camera – subscription required)

However, light field cameras are only half of the story. The other half of the story is the display side. Just as light field cameras can allow for multiple ‘virtual’ optical viewpoints, the same is true for light field displays. That means a potential to overcome the disadvantages that come when the actual focus distance of a display doesn’t match the viewer’s focus (for example in augmented reality applications) or when flat images cause conflicts between apparent depth and convergence and accomodation. I’ll come back to that topic in my next article

– BR