There are a lot of good things happening with educational VR across the country, yet I find that many of the great stories about VR in classrooms somehow seem to fly under the radar. Yes, good things are in fact happening, but often no one knows about them.

That’s because educators rarely toot their own horn; it’s also because the education industry is highly isolated and successful programs are often geographically pigeonholed. Rarely do successes get the broad recognition they deserve. Here’s another VR-in-School Success Story.

While many companies fire away in a dogged rush to sell VR experiences and content to classrooms across the world, other educators are pursuing an entirely different pathway: the pathway of creating their own VR. Take as an example the work now being done at Tampa Preparatory School, which has rolled out its own “virtual reality creation lab” for students. The school began its “IDEA Lab” (Innovate, Design, Explore and Apply) by retrofitting a cluttered storage room in its school library, a space cluttered with archaic and unwanted paraphernalia from past decades. They outfitted the lab with VR laptop stations, which are connected to an Epson projector that displays a seven-foot image (2.1 m) from any of the laptop screens onto a Walltalker dry-erase wall.

VR ‘prosumers’ at Tampa Preparatory School

VR ‘prosumers’ at Tampa Preparatory School

Interestingly, their original ideations about creating this lab went far beyond the notion of simply creating virtual reality content and applications. According to Chad Lewis, the Technology Director at Tampa Preparatory School, the principal purpose is to empower students to “learn coding, 3D modeling, game development, collaboration, and design thinking.” Since the creation of the IDEA Lab was a student-driven initiative, it makes sense that the students’ own ideas drive the application development emerging from this lab. As an example, Lewis tells this story:

“One of the students was having difficulty visualizing molecule binding in chemistry. (Sometimes a molecule might be behind another, which is difficult to draw in 2-D space on paper.) Virtual reality became the perfect solution, because it’s a 360 environment where students can rotate, zoom and move around to see the entire structure.“

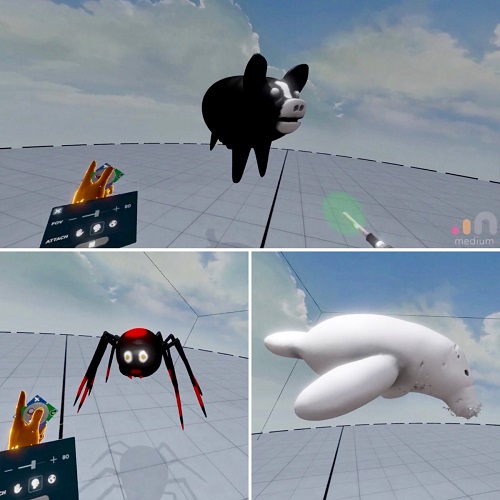

Examples of student-produced work

Examples of student-produced work

Chad LewisOverall, Chad Lewis describes their project this way: “It has been transformational.” Not only have they been able to “branch out beyond computer science, they have moved into areas like chemistry and physics.” According to Lewis, the “secret sauce” for the school’s success in the operationalizing their virtual reality efforts lies with their ability to “allow students the opportunity to pursue their passions.” He worried, “Many times educators’ egos get involved and we think that we must be the sole source of knowledge and experts in a particular subject. This can really hold learning back, especially when it comes to technology which changes so quickly.” He adds: “students need time, space and resources, as well as support and encouragement.” Their efforts have been contagious. Lewis exudes great pride in announcing:

Chad LewisOverall, Chad Lewis describes their project this way: “It has been transformational.” Not only have they been able to “branch out beyond computer science, they have moved into areas like chemistry and physics.” According to Lewis, the “secret sauce” for the school’s success in the operationalizing their virtual reality efforts lies with their ability to “allow students the opportunity to pursue their passions.” He worried, “Many times educators’ egos get involved and we think that we must be the sole source of knowledge and experts in a particular subject. This can really hold learning back, especially when it comes to technology which changes so quickly.” He adds: “students need time, space and resources, as well as support and encouragement.” Their efforts have been contagious. Lewis exudes great pride in announcing:

“Now we have a student VR Creation Club and next year will have a VR/AR creation class. In addition this lab has led to a new STEAM initiative. We have one of the art classes creating virtual sculptures with an app called Medium on the Oculus Rifts. They can save these sculptures as 3-D models and either print them out on the 3-D printers or send them to the computer science students to use as assets in their Unity projects. It’s a great way to expose art students to 3-D modeling technologies.”

Chad Lewis in his elementAs far as the cost issues of virtual reality, Lewis was not worried for long: “Actually, the entry point into VR creation was less expensive than many schools are paying for mobile virtual reality kits, but these are “one trick ponies”, primarily for solely immersive experiences with very little student interaction and no creation options.” “Creation is the highest level of learning”, argues Lewis. “Each virtual reality creation station cost us around $1800 all-in.” He adds: “Keep in mind that the lion’s share of the cost was the laptops, which are also used for other functions [and classes] like 3D modeling and AutoCAD”.

Chad Lewis in his elementAs far as the cost issues of virtual reality, Lewis was not worried for long: “Actually, the entry point into VR creation was less expensive than many schools are paying for mobile virtual reality kits, but these are “one trick ponies”, primarily for solely immersive experiences with very little student interaction and no creation options.” “Creation is the highest level of learning”, argues Lewis. “Each virtual reality creation station cost us around $1800 all-in.” He adds: “Keep in mind that the lion’s share of the cost was the laptops, which are also used for other functions [and classes] like 3D modeling and AutoCAD”.

Some Concluding Thoughts.

What you are seeing and reading here has been around for a long time, piggybacking onto numerous technologies over the decades: the emergence of the prosumer. The portmanteau prosumer first appeared in books around the year 1905, rising greatly in usage in the 1970s and 80s. At that time, McLuhan and Nevitt suggested that “the consumer would become a producer” and the futurist Alvin Toffler carefully re-cast the term “prosumer”, predicting that the function of producers and consumers would slowly “begin to blur and merge.”

The big takeaway here is that the educational arena may already be equal parts prosumer and consumer markets for virtual reality manufacturers. Chad Lewis of Tampa Preparatory School understands this well. When I first met him, he intently announced the creative tension between “consumer versus prosumer” of VR, laying down his stakes in his unique pursuit of the latter. –Len Scrogan