The first speaker was Stefan Peana of Dell who talked about Adobe-compliant display design, compliance and certification. Over the years, as the industry has developed from the early days, when legibility was the only criterion, the display has developed enormously. VESA compliance was important to ensure supply and development of displays as a commodity. Now resolutions and the ‘retina concept’ have become important. Front of screen performance is a key part of the user experience.

At the moment, notebook displays cannot typically cover the AdobeRGB gamut, but often the specification is, for example, 96%. However, the gamut triangles may not overlap, so there are Adobe colours that cannot be reproduced, and other colours that the display can show, but where there is no data. That means you can’t be sure of seeing what you want if you work in the Adobe environment. Calculating how the 4% applies to a colour volume is quite complex. If you meet AdobeRGB, then you broadly meet the UltraHD Alliance Premium requirement of 90% of DCI P3.

Professionals and advanced users are suffering from an inability to get accurate colours. There has to be an effort to re-map displays to the colour space and that can cause colour distortion. Many cameras (including smartphones) can be set to capture in Adobe colour space, but users may be dissatisfied if they have to spend time making adjustments and can’t get accurate colour.

There is currently no Adobe Display standard specifically for mobile products. Peana then explained the AdobeRGB gamut and how the green was changed compared to sRGB. Brightness should also be 160 cd/m² with a certain gamma (2.2) and controlled ambient lighting to ensure consistency. There really need be to improvements to this, as nobody uses the settings, Peana added. He said that there are now sensors that can detect colour temperature and brightness and you should be able to use this to optimise performance. He also said that 400 cd/m² was set as the target brightness for all media and that is a challenge in a notebook. There are issues with dimensions, power consumption and thermal management. You need a good aperture ratio, which means the panel needs to be based on IGZO or LTPS, but you also need, probably, a collimated backlight. You have to specify new colour filters and narrower bandwidth LEDs.

The company made several test displays and eventually got to be able to meet the AdobeRGB gamut. Getting the factory to ensure compliance is tricky, as you need to check if the triangles are accurately set and also the white point. The display is measured at the time of production and the data is stored as part of the EDID data in the display. Samples were sent for testing in Dell’s labs. The first notebook to meet the Adobe compliance was the XPS-15, which was shipped earlier this year and has been independently reviewed with success.

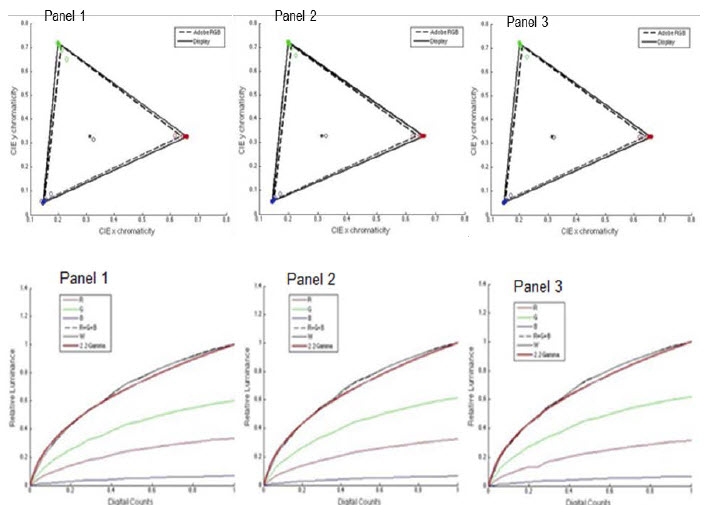

These are the results of the tests on the three samples.

These are the results of the tests on the three samples.

There is a certification process, but displays can be self-certified or externally-certified. Peana said that users should not have to go through a complex process to get accurate colour. He said that providing a good display means that photographers can use Adobe directly to edit images immediately, without waiting to have to go to their offices. The project needed the support of eColor, RIT and Sharp as well as Adobe and Dell.

In response to a question, Peana said that he would like to move to a perceptual colour space for measurement, but that the display industry is slow to change. He also said in questions that you should be able, these days, to accurately map between colour content and displays to take account of ambient illumination. It was pointed out during questions that Microsoft has said that it wants to move Windows from sRGB to Rec.2020 and then to ACES, which would mean that all the colours could be captured and mapped to a display.