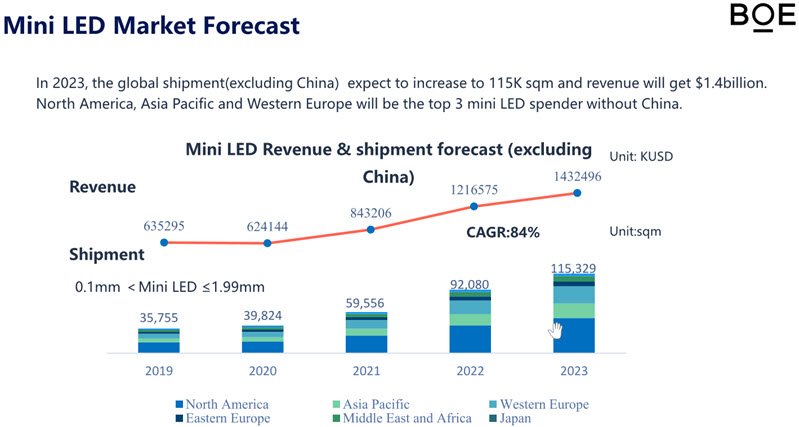

The company presented some interesting data on the size of the direct view LED display market and said that the overall value of the market was $5.7 billion in 2019, with around 31% of the value of the market being in the small pitch category of pitches <2mm (which BOE regards as miniLED).

The market in terms of area was 140K m² with China representing 74% of the area and with North America (15K m²) and Western Europe (6.6Km²) in second and third place. (No source was given for the data, but it looked credible to me). A quick calculation gives a value of around $13K per square metre. That’s an interesting contrast to LCDs for TV which sold a couple of years ago for anything between $115 to $200 per sq metre at the lowest point of the market and between around $200 and $250 recently.

The market outside China is growing fast, with CAGR of 84% over the next couple of years and that part of the market will, alone get to 115 k m2 with a value of $1.4 billion by 2023. BOE ranks Leyard and Absen neck and neck at the top of the market, with Unilumin in third, then Samsung and Liantronics. These five brands take 53.3% of the small pitch LED business.

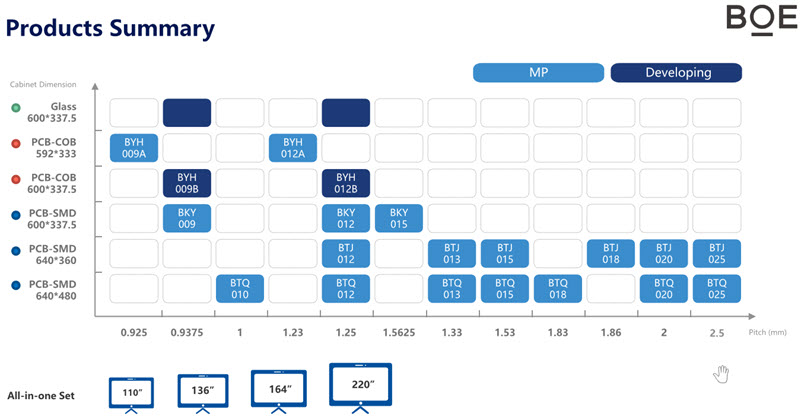

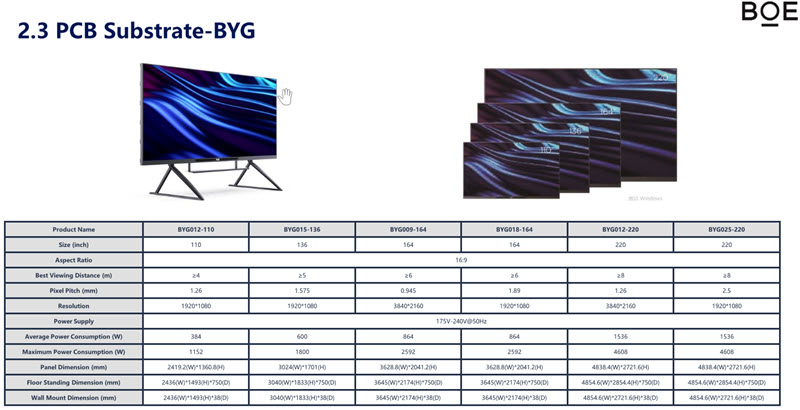

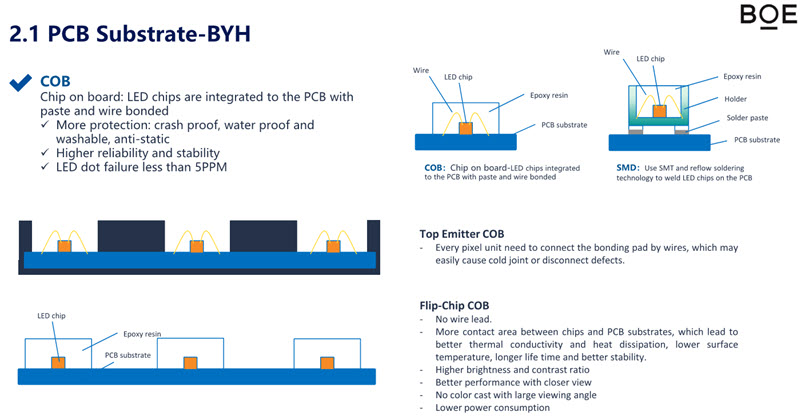

BOE wants to be a significant player in this market and has been developing a range of products starting with 4:3 and 16:9 modules of up to 2.5mm pitch, initially using surface-mounted (SMD) LEDs and developing into COB technologies as well at pitches of 0.925mm, 0.9375mm, 1.23mm and 1.25mm. These products have been based, as most LEDs have been for a long time, on devices mounted on printed circuit boards (PCBs).

As well as modular displays, BOE is developing All-in-One or monolithic sets at 110″, 136″, 164″ and 220″.

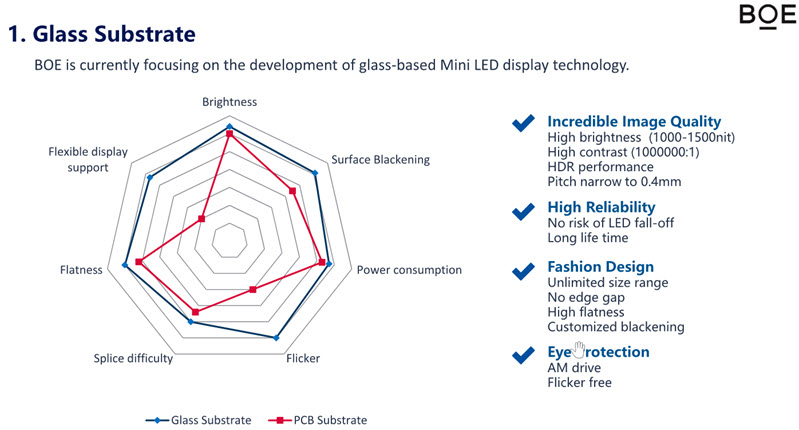

However, interesting though that all is, it’s not really new. What is new for BOE is the development of glass as a substrate for the LEDs, rather than a PCB. Now, the use of glass with an active matrix has a number of advantages. First, the use of active matrix addressing reduces flicker. Second, the LCD makers have huge investments and knowledge of how to make active matrices for LCDs and OLEDs so can exploit that by switching to glass. The glass would be better than the PCB at diffusing the heat from the LEDs- a significant issue that limits the brightness of LED displays.

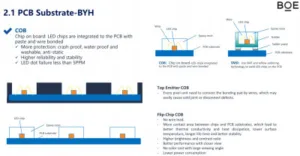

Traditional SMD LEDs are quite fragile and it is easy to damage them with impacts which can cause the LEDs to become detached. That was one of the reasons for a move to COB (which looked a big trend a couple of years ago, but which didn’t quite develop as much as forecast). BOE showed an interesting slide that shows the difference between SMD LEDs and top-emitter and flip-chip COBs.

BOE also said that the surface blackening is better with glass and makes flexible displays easier to support. It may also be a little easier to splice the modules. The advantages are shown in the graphic

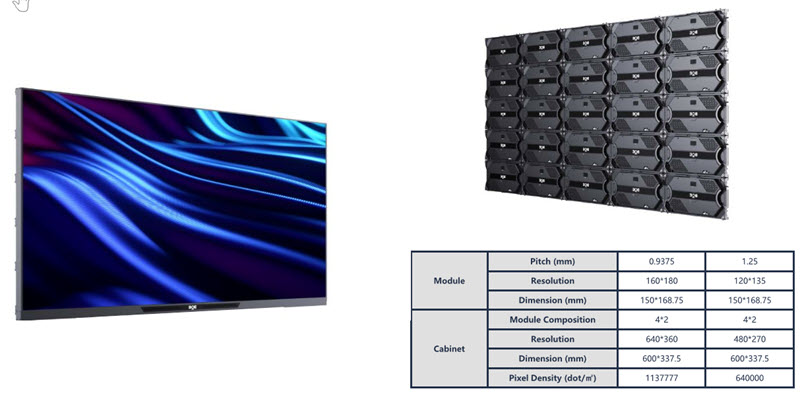

BOE will have two glass based systems with 0.9375 or 1.25mm pitch. The details are in the table, but note that the physical dimensions are the same, with eight modules per 16:9 cabinet (which are the same size as the BYH series PCB-based cabinets). Note that the individual modules are just 150 x 168.75mm, which means that they are in the range of LTPS (or later, LTPO) technology, so that the transistors on the substrate can be better than AM-LCDs. The move to flexible OLEDs has meant excess capacity in rigid glass LTPS making, which is an advantage in pushing costs down.

Clearly, as it does in LCD and OLED, BOE has big ambitions in LED and will use its technology and industrial power to promote the technology. We have reported on the deal between BOE and Rohinni, which makes systems for placing the LEDs much more efficiently than traditional ‘pick and place’ processes. As well as working on direct view LEDs, BOE and Rohinni have a joint venture to make miniLED backlights, BOE Pixey. (I Saw It, but I Didn’t Understand It) (BR)