There was a time when the number of aspect ratios on electronic displays was quite limited, but that has changed dramatically, now.

In the cinema, for many years (from 1932 to 1953 according to Wikipedia) the Academy aspect ratio of 1.375:1 was widely adopted, while for TVs, the standard for TVs was 4:3 (or 1.33:1). The cinema ratio was based on the availability of 35mm film and the technical constraints, while the TV shape was a result of the optimum cost of a CRT-based TV being 4:3.

In the 1950s, CinemaScope and Panavision came along which used optics to ‘stretch’ the width of the image from the basic shape of the film to 2.35:1 on the screen.

When the cinema industry went digital, with the DCI standard, the format was set at 1.85:1 – a bit wider than HDTV. (for a fuller look at all the different formats used, check https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aspect_ratio_(image)

TVs Were Standardised

In the 1990s, TV widescreen formats were adopted for the move to HDTV and they have standardised around 16:9 (1.77:1). There was no special reason for this choice of format, but it seemed to fit between the 4:3 format and the widescreen cinema formats. The TV industry loves standards and is good at implementing them, so TV widescreen formats have consistently remained at 16:9 format since and the development of UltraHD TV has not changed this. (I once spoke to someone who served on the committee that came up with 16:9 for TV. He said that there was no real reason for this particular value except that 16:9, being 4:3 squared had a certain mathematical elegance to it!).

Some TV makers have played with 21:9 formats for flat panel TVs. Although this matches closely to the 2.35 format, there is relatively little content that is broadcast in that format and so it really didn’t catch on. At the time of the launch of those panels, the makers of the panels were saying that the extra width of 21:9 panels could be used to show Facebook and Twitter content alongside 16:9 content. However, I argued that Twitter and Facebook are personal, while TV is mainly social in many homes, so I didn’t expect this catch on. I can just imagine my wife’s reaction if I started making Facebook posts while she was watching a programme! Personal communications will take place on personal devices.

IT Monitors Have Gone Wide

In IT, CRT monitors were 4:3 or 5:4 aspect ratio, but LCDs can be almost any shape. In the early days of LCD monitors, widescreen versions were made with a 16:10 format. A lot of corporations standardised on 16:10, which caused something of a problem when panel makers moved monitor panel production to fabs designed for TV, where 16:9 was more economic. Despite pressure from panel makers to move to 16:9, 5:4 and 16:10 panels remain in the market for IT monitors.

Whereas I didn’t think much of 21:9 for TV, in monitors, 21:9 makes a lot of sense, as having data too high above the eyeline is not good ergonomics. So, making screens bigger works by increasing the height and width, but once you get to around eye height, it’s best to just expand the width.

Notebooks and mobile devices originally followed the 4:3 aspect ratio, then 16:9 – I still remember the first Sharp ‘Widenote’ PC. The shape worked well. Most notebooks, these days are 16:9 but some portable devices such as Microsoft’s Surface Pro 3 have a squarer format at 3:2 and Apple’s iPad is 4:3 aspect ratio.

The most recent top-of-the-range phones have moved from 16:9 to 2:1 (or 18:9) aspect ratios as makers try to extend the area of the display surface to cover the whole front, without increasing the width of the handset, which would making holding the phone more uncomfortable.

LG’s G6 was one of the first smartphones to use a 2:1 aspect ratio

LG’s G6 was one of the first smartphones to use a 2:1 aspect ratio

Cinemas Can Mask

Now, of course, in the cinema business, you can always use curtains to mask to a particular format that will fit within the overall dimensions of the image. On the other hand, when you have a flat panel display, the person creating the content has the choice of cropping the image to fit the shape of the screen, or showing it at the right aspect ratio, but with black borders. These borders tend not to be popular, so usually the decision is to crop (or ‘pan and crop’) to make the best result overall.

At CEs in 2016, Samsung did show an intriguing ‘reconfigurable’ display made with motorised LED panels that could change from 16:9, by splitting the panel in two and rotating the halves before recombining them. Once recombined, the display has an aspect of 18:8 – 2.25:1 (2 off 9 x 8 halves) and close to the 21:9 format. This might be a feasible design concept for future TVs, if microLED can enter the TV industry as they should not need bezels. (Check out the video below at 4 minutes 20 seconds).

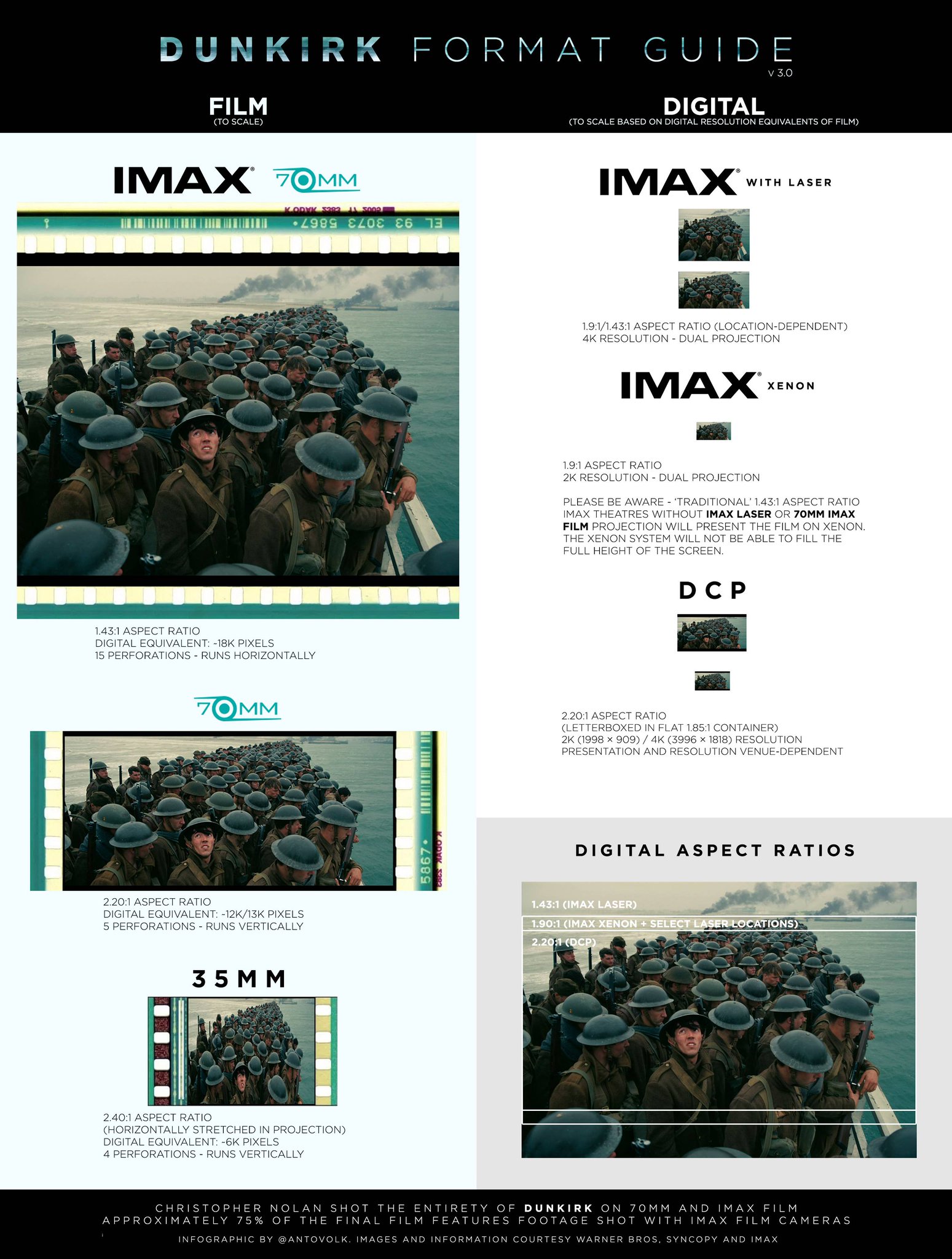

All of this was brought to mind by an excellent example of detective work by film buff and and president of the University College London film society, Anton Volkov, who put together a great infographic that shows all the different ways you might see the summer hit move, Dunkirk. Unusually, Dunkirk was shot on 65mm IMax and standard film and the IMax format is 1.43 to 1, so quite ‘square’.

Dunkirk aspect ratios – click for higher resolution.

Dunkirk aspect ratios – click for higher resolution.

Volkov points out that relatively few people will see the film with the full ‘creators intent’. Most of the viewing will lose some of the height of the images.

Creative Intent?

Display specialists often talk about the issue of creator’s intent, the idea that the creator has one image in mind and, arguably, the duty of those between the content and viewer’s eyes is to preserve that intent. Generally, this is about frame rates or colour gamuts. Arguably, though, the issue of aspect ratios has a potentially bigger impact, but it’s hard to see how the integrity of the artist’s vision can be preserved, given the range of devices being used to view content, now. Bob Raikes