As regular and long term readers will know, I’m keen on trying to spot inflection points in the development of the industry – moments after which the industry will never be quite the same. Occasionally, I spot one that others don’t, but this time, I’m covering one that anyone that watches the industry will have seen. Still, I think it’s worth looking at.

A few days ago, Samsung’s Display business announced that it would completely end the manufacture of LCD displays by the end of this calendar year. Like the deal between Sharp and NEC last week, I had a brief moment of surprise, but this moment has been signposted for a significant number of years.

I think it was at IFA in September 2010 that I met with Wonkie Chang, who was then head of the LCD business of Samsung to brief him on the European TV market and its developments. Even by that time, forecasts for LCD revenues were flattening or even declining as CRTs had broadly been replaced in new product sales for the key applications of monitors and TVs. However, forecasts for volumes were largely still growing as flat panel technology moved out from the relatively rich regions in the developed world into developing markets, where ASPs had to be a lot lower.

I asked Chang how, given the lack of revenue growth in the markets even that long ago, he could persuade his finance department to find the huge investments needed for new LCD fabs when there was no additional revenue? He really didn’t have an answer (there really wasn’t one!). Even though the logic of the LCD business was always that a fab of a new generation typically costs around 40% more than the previous generation, the factory will produce double the output. That allows companies that keep investing to stay ahead of competition by reducing the capital cost element.

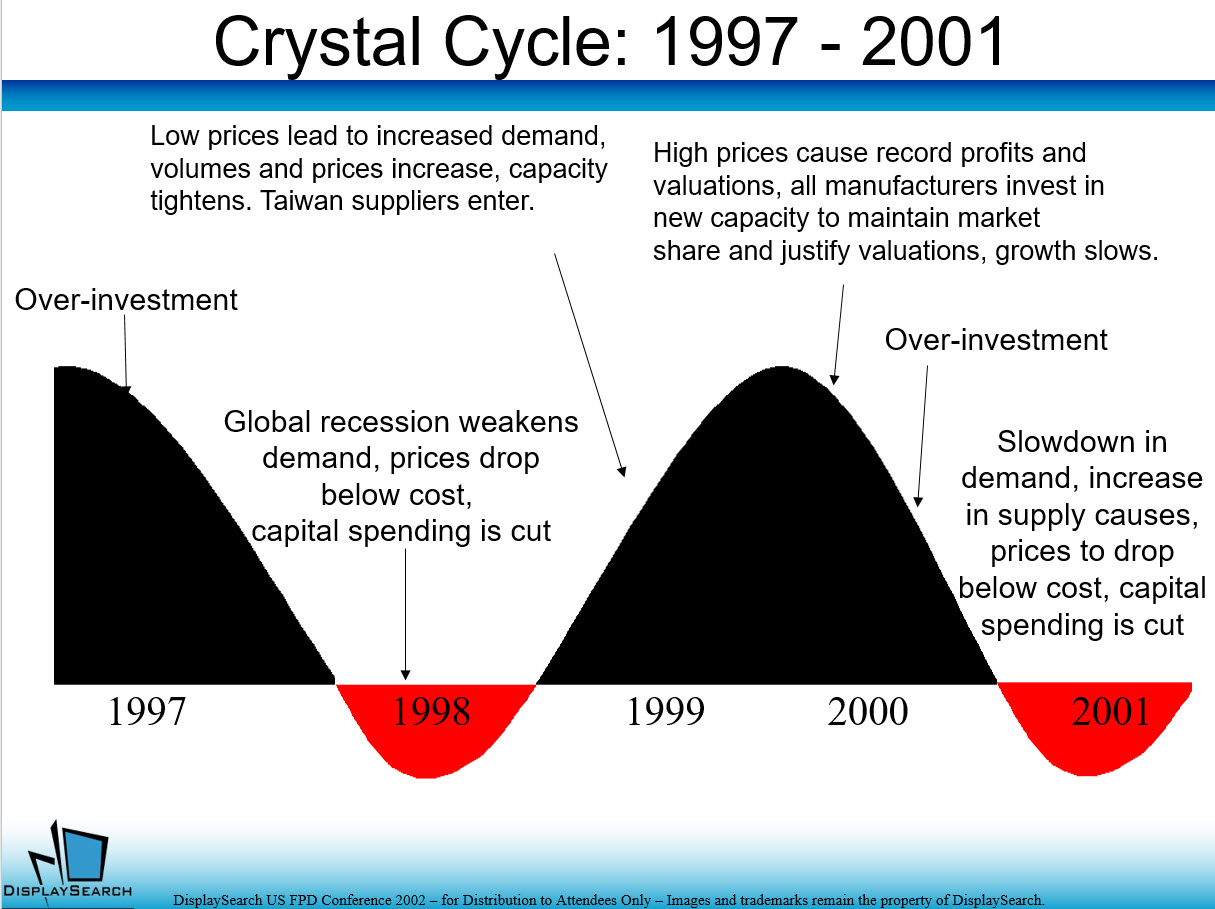

Samsung had a particular advantage over others. Ross Young, then of DisplaySearch and now of DSCC, was the first (in 2002!) that I heard talking about an important advantage that Samsung had. The size of the overall company and the cash from businesses including semiconductors allowed it to invest at the down point of the crystal. For most of the companies (AUO, Innolux/CMO and LGD in particular), finance from the stock markets to invest were only really available when the LCD price was at the high point of the cycle, so their profits looked good. By the time that investment was put into factories, the cycle had turned, so it arrived at the negative point of the cycle, when prices were low.

The crystal cycle in 2002 – it’s still basically the same!

The crystal cycle in 2002 – it’s still basically the same!

Samsung had enough money available from its other businesses that it could invest when things were bad so that its capacity came on stream just as the prices were rising, so it was able to really reap the benefit. Ross explained this at a talk at his (much missed) US FPD conference in San Diego and I remember going up to him afterwards and saying

“Ross, you have to stop saying this, if everyone invests at the wrong time, maybe the cycle will never turn positive!”

Anyway, the key dynamic of industry development was moving to new generations. In the summer of 2007, Sharp confirmed that it would build a G10 fab at Sakai, when others, including Samsung, were at G8 or G8.X. Previously, we would have seen Samsung doing the same but although Samsung talked quite a lot about building a G10 fab, it never did. Sharp’s fab came on stream in 2010 and gave Sharp a cost advantage in the 60″ to 70″ size range. However, a ‘perfect storm’ of the Fukushima disaster, the end of Japanese subsidies for TV purchase and the completion of the switch to digital in Sharp’s home TV market in 2011 combined to put Sharp into financial trouble before it could makes its money from its new fab.

Samsung did continue to invest in G8 capacity, but the writing was on the wall and David Barnes gave a great talk at SID 2012 (I miss his talks which were always entertaining as well as educational!) when he talked about the “OLED island”. He said that Samsung’s quest to build OLEDs for smartphones and (abortively) for TVs might work if only they developed the technology – i.e. they had an ‘island’, but that if the others, especially the Chinese, found the island, there would be no profit. That remains the case, really, except that it was LG that got to the OLED TV island, while Samsung made it to the smartphone island. (BR)