There’s a topic that I have been looking at for a long time, without making much real progress – but which finally became clearer after a webinar that I attended last week. That topic is ‘the problems of blue light from displays’ and more specifically, what the TÜV Rheinland ‘low blue light’ mark means.

It all started three years ago, nearly (my file records a creation date of 1st December 2016) when I saw a release about the launch of an ‘Eye Comfort Mark’ with Lenovo. That was when I started the process of trying to find out more. I checked the website, but couldn’t find out what the TÜV Eye Comfort label meant. In its release, TÜV said that “The use of the keywords “Eye Comfort” confirms that the product satisfies TÜV Rheinland’s test criteria.”. I sent several emails to TÜV, and, if I remember correctly, filled in an enquiry form. I also spoke to TÜV representatives at several trade shows, including MWC in Barcelona. However, I got no nearer finding out what the test criteria were.

I got to the stage of describing TÜV as a ‘secret society’. It’s amazing that a company that depends on people recognising its labelling should prove so poor at communicating with those interested in those labels. I suspect that the firm is more interested, really, in the clients that provide the money, than in spending time and money to communicate its ideas. (so, if you are one of those clients, it might be worth asking TÜV what it is actually doing to raise awareness of its labelling schemes).

Anyway, a few weeks ago, I got an invitation to a webinar that, at least, covered the blue light requirements that TÜV is promoting. I couldn’t attend the live presentation, but there was a ‘catch up’ session that you can see here. http://www.bluelightsummit.com/ The presentation is quite a long one, and I found what I was looking for around 37 minutes into the video and explained by Stanley Liu of TÜV.

The presentation was part of a push about the blue light issue that explains how TÜV is working with Eyesafe, a commercial organisation that is trying to own the issue of blue light ‘toxicity’. It also announced that EyeMed – a major insurer – would be recommending Eyesafe-approved products and offering certified solutions, although it was acknowledged in the webinar that the science behind the issue is still under investigation.

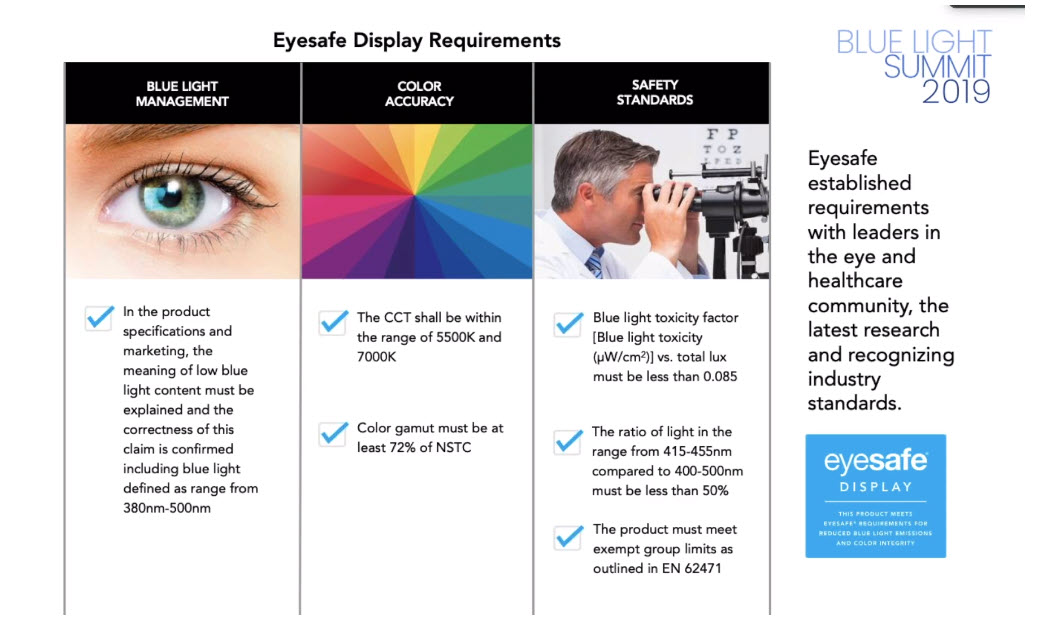

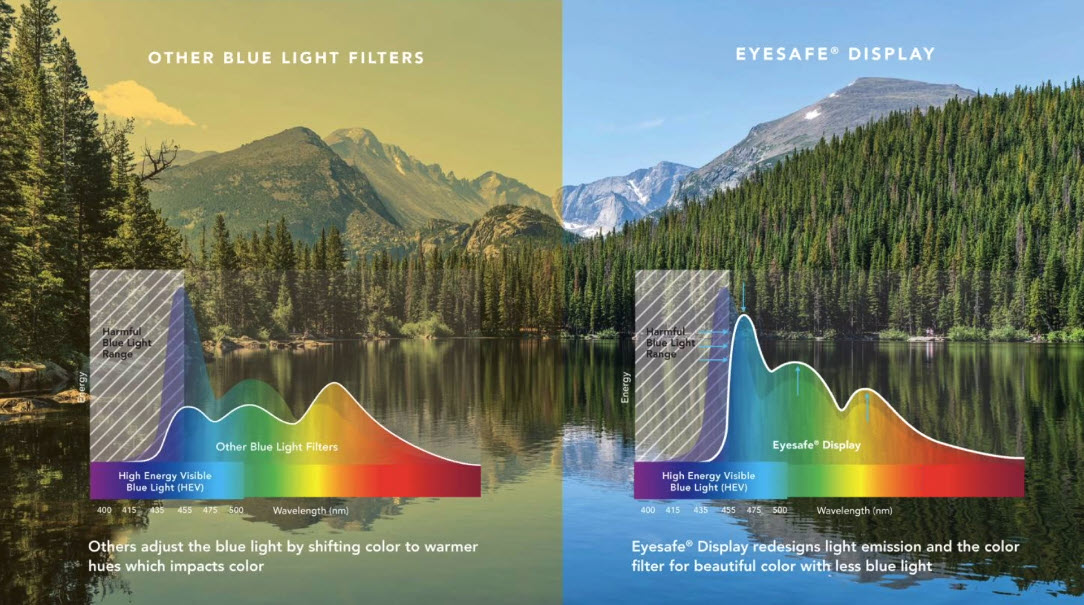

Eyesafe announced its first requirements in May 2019 (with Dell) and updated them to V1.1 by last month, with a V2.0 already under development. Eyesafe says that it is trying to maintain colour accuracy as well as reducing blue light

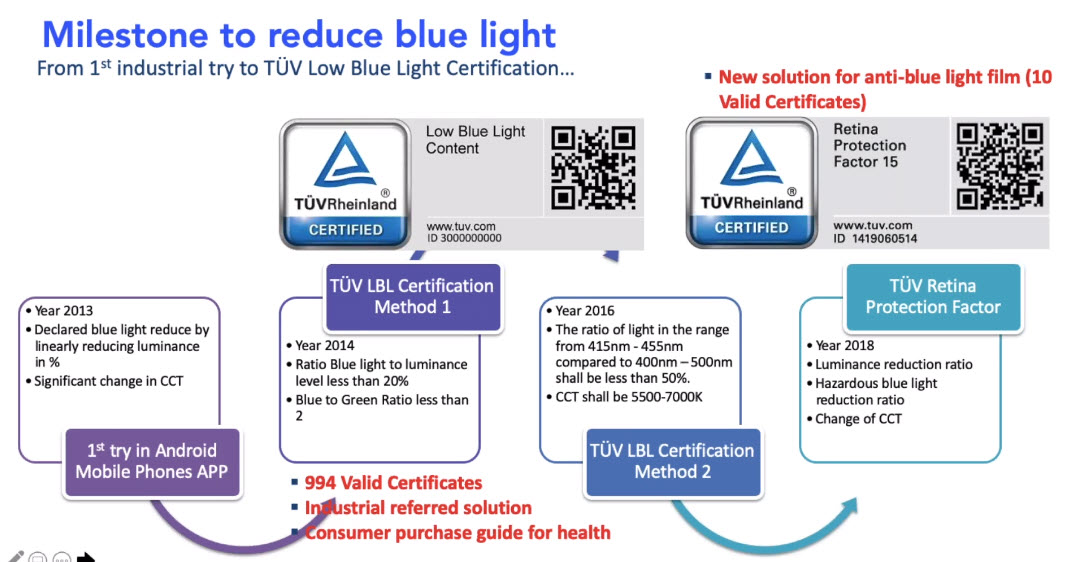

In the presentation, TÜV presented a time line of what it has been doing in the ‘blue light’ area since 2013.

TÜV has found that many of the software solutions to reduce blue light have a negative impact on colour performance and accuracy by simply reducing the blue level.

TÜV has issued almost 1,000 certificates to valid products for its 2016 label.

In 2018, the firm introduced a ‘Retina Protection Factor 15/20/30’ label which was developed with Eyesafe for accessory films and for which there are now ‘more than ten’ products, mainly in smartphone. They do change the colour temperature, but less than other approaches. At the moment only RPF 15 films are in the market.

Now, there is another new label for displays, the ‘Eyesafe Display’ label.

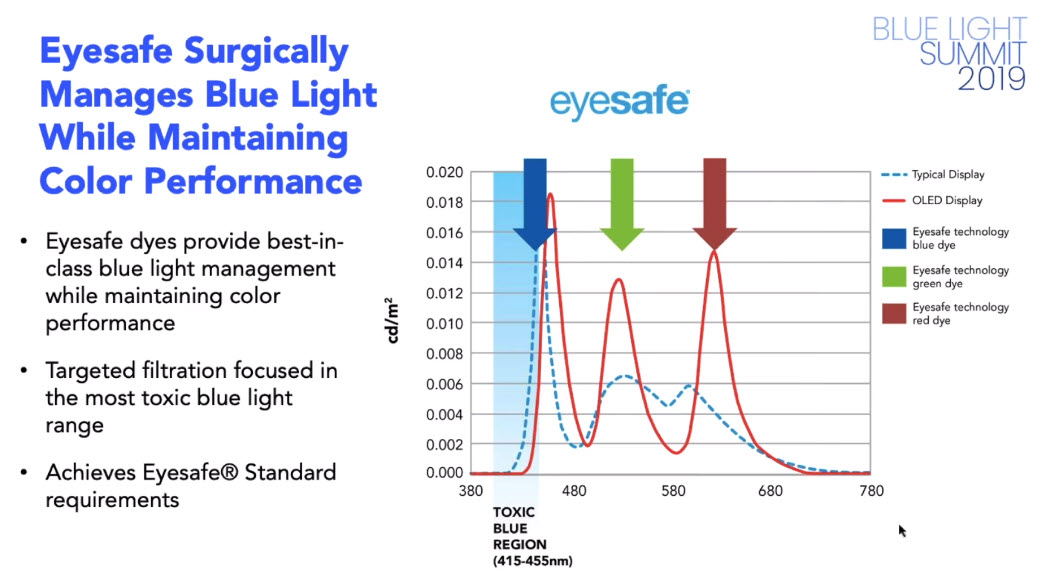

Eyesafe’s CTO explained in the webinar that OLEDs typically emit less of the ‘toxic’ blue frequencies than LCDs, although I was slightly surprised to hear him claim that OLEDs provide more brightness than LCDs (although he may have just been thinking of smartphones).

In questions, Eyesafe said that its methods do allow the use of displays with P3 gamut.

Conclusion

Perhaps the deal between Eyesafe and TÜV represents the understanding by TÜV that it is really not up to the job of promoting its blue light activities, as I have found. That’s probably good news for the display industry. Certainly, it would be good to see carefully considered and scientifically-based communication around this topic. Much of what I have seen from less sophisticated marketeers runs the risk of raising the question ‘if blue light is so dangerous, why don’t you adopt this technology for all your products?’.

Of course, one of the challenges of all of this kind of research is that if you believe that some damage may be caused to human eyes, it’s hard to set up a double-blind test of damage on humans, so much of the research is carried out on animals and may, or may not apply in the same way to humans. (BR)