On Wednesday, January 16th, the SMPTE NY Chapter had a meeting on high dynamic range (HDR) capture, content and display.

This was held at the Microsoft Training Center in New York and was titled “HDR Workflows: Beyond the Technical Silos.” This meeting was described as being “a debate on integration, relative importance and relationships between HDR lenses, cameras, infrastructure and screens.”

Panelists at the SMPTE Meeting. Left to Right: Larry Thorpe, John Humphrey, John Mailhot and Mark Schubin. (Credit: M. Brennesholtz)

Panelists at the SMPTE Meeting. Left to Right: Larry Thorpe, John Humphrey, John Mailhot and Mark Schubin. (Credit: M. Brennesholtz)

There were four panelists at the meeting:

- Larry Thorpe, Sr. Fellow at Canon USA and one of the worlds experts on lenses. He was awarded an 2014 Engineering Emmy Award for lifetime achievement and in 2015 he received Honorary Membership in SMPTE – the highest award the society offers.

- John Humphrey, VP Business Development at Hitachi Kokusai. As Chief Engineer, he built and operated multiple mobile trucks, is a life-certified SBE CPBE and a former SMPTE Section Manager.

- John Mailhot, CTO of Networking and Infrastructure at Imagine Communications. He began in 1990 as part of the AT&T-Zenith team, responsible for system architecture and integration of the digital spectrum compatible high-definition television (DSC-HDTV) system prototype. Later, at Lucent Technologies, he had a variety of roles, starting with the technical lead for the Grand Alliance encoder. More recently, he was the editor of the SMPTE ST 2110 media over IP standard.

- Mark Schubin, Engineer, Archivist, Evangelist – defies description. He is a winner of multiple Emmy awards and a SMPTE Life Fellow. His earliest work on HDR was in 1975.

- Josh Gordon was the moderator of the panel session. While he is currently a Marketing Consultant, he has deep roots in the broadcast industry, including 20 years as a journalist at Broadcast Engineering. His four books have been translated for publication in Germany, China, Korea, and Taiwan.

As can be seen, these men are all respected experts in their fields. This was not a panel of marketing people with product to sell who learned the HDR buzzwords the week before the meeting. Instead, it was a group that when they talk, you should listen.

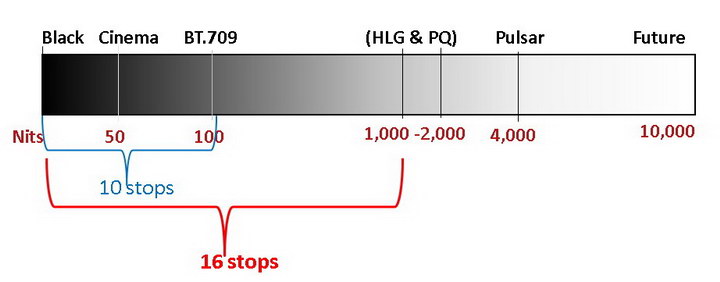

Light Level range of HDR systems (red) and SDR (Blue). “Pulsar” refers to the 4000 nit Dolby Pulsar reference monitor. (Credit: SMPTE)

Light Level range of HDR systems (red) and SDR (Blue). “Pulsar” refers to the 4000 nit Dolby Pulsar reference monitor. (Credit: SMPTE)

The meeting began with a very brief overview of HDR by John Humphrey which covered issues like the definition of Electro-optical transfer function (EOTF), Opto-electronic transfer function (OETF), opto-optical transfer function (OOTF), the light level ranges associated with HDR and the various HDR formats and profiles. This part of the session could be brief because not only was the panel full of experts but most of the audience was familiar with HDR technology, standards and terminology.

After the introduction, Larry Thorpe was the first speaker in the main session. He discussed the lenses and the lens properties needed to acquire HDR content. I had realized that different lenses with higher resolution were required to acquire 8K, UHD-2, 4K or UHD cinema and television content, compared to the lenses needed to acquire 2K or FHD (1080p) content. I hadn’t thought about the fact that different lenses were also needed to acquire HDR content as well, and the lenses designed for 8K or 4K are not necessarily optimized for acquiring HDR content at these resolutions. Lens-related HDR problems are particularly likely to happen in the dark regions of scenes that also have strong highlights.

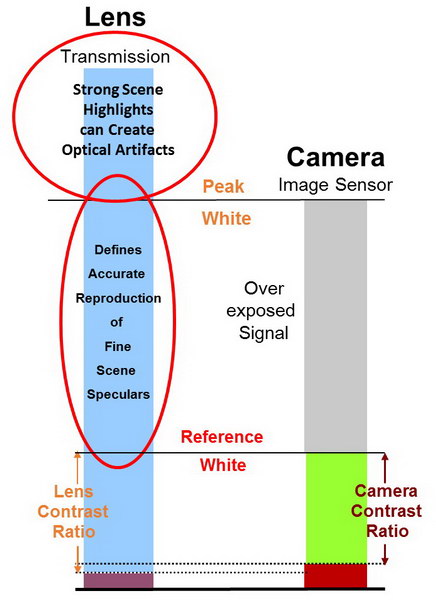

Light level comparisons for lenses and camera image sensors. (Credit: Larry Thorpe via SMPTE)

Light level comparisons for lenses and camera image sensors. (Credit: Larry Thorpe via SMPTE)

No lens is “perfect” and all lenses produce some illumination at the image sensor where there should not be any illumination. Flare and veiling glare are two problems that can be encountered. In fact, with the additional lens elements needed to produce 8K or 4K resolution compared to 2K resolution, these problems can be made worse, unless extraordinary care is taken during the design and manufacturing of the lens.

Thorpe said every camera, HDR or SDR, has a noise floor and the HDR noise floor must correspond to very low light levels. The goal of a lens designer is to ensure that the veiling glare and other problems of the lens are below the noise floor of the HDR camera. In other words, when the lens and camera contrast are based on the reference white, the lens contrast should be higher than the sensor contrast. This ensures that the range of the camera, e.g. 16 stops for a modern HDR camera, is not compromised by the camera lens.

One issue not discussed by Thorpe is that high-end lenses, especially zoom lenses, can be extraordinarily expensive, even compared to a high resolution, HDR image sensor, so it is not always possible to have the sensor as the limiting factor in dark scenes rather than the lens. Since fixed focal length lenses are easier to make and have fewer optical problems than zoom lenses, I wonder if HDR may lead to the return of “Prime Lenses” with fixed focal lengths for HDR rather than the zoom lenses that have recently come to dominate content acquisition.

Even the task of correctly shading three cameras for a SDR production can be frustrating. (Credit: Tektronix)

Even the task of correctly shading three cameras for a SDR production can be frustrating. (Credit: Tektronix)

The next speaker was John Humphrey again, talking about cameras and HDR. He talked about the problems of camera video shading, which is the alignment of multiple cameras in a production to the same video performance.

“Multiple Cameras” understates the problem: there was an article in the New York Times saying over 50 cameras had been used at Sunday’s NFC championship football game. Presumably the upcoming Super Bowl will use even more. Not only are a lot of cameras used, but multiple camera types are used in any production like this, from large, fixed mount cameras with quarter-million dollar lenses to shoulder-mounted and hand-held portable systems with built in zoom lenses. For HDR to work, the black level, reference white, peak white and OETF for all cameras in a production must be set to be the same. Otherwise, the director in the control truck will have problems smoothly cutting between the different cameras in a production.

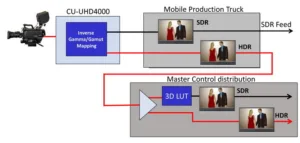

A live HDR program will typically generate two SDR feeds and these feeds may differ from each other. (Credit: John Mailhot via SMPTE)

The next speaker was John Mailhot who spoke on what happens to the pristine HDR master you have made and are so proud of after you turn it over to the distribution chain. One of the problems is that converting from one EOTF to another is normally not much of a problem. However, if there are multiple EOTF conversions, the small changes introduced by each of the multiple conversions can degrade the image quality. This is similar to the degraded resolution after multiple copies of analog media such as film.

This problem begins before you even have your master because the OETF of the input signal from the camera, proprietary to each camera maker and normally some form of Log OETF, must be converted into the EOTF used in post-production, which may not be the same as the EOTF used for distribution. In live productions, there are normally two SDR signals – one derived directly from the camera and the second derived from the HDR master.

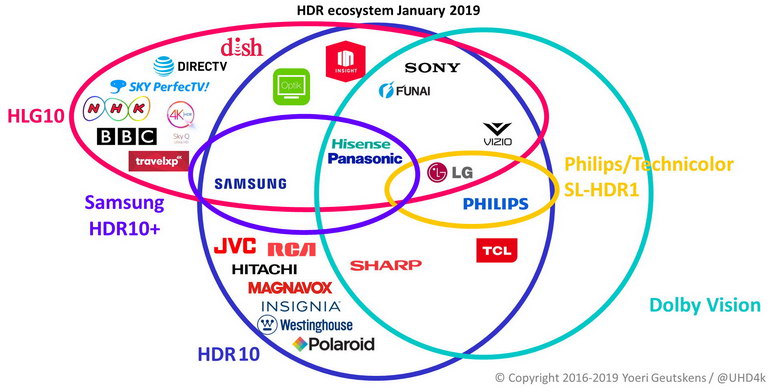

HDR support by TV brands and broadcasters/operators (Credit: Yoeri Geutskens via SMPTE)

HDR support by TV brands and broadcasters/operators (Credit: Yoeri Geutskens via SMPTE)

When the master is then delivered for distribution, the EOTF may be changed again by the network or other distribution channel. This is normally done automatically, out of the watchful eye of anyone concerned with the artistic content of the signal. All the speakers expressed special concern for the situation shown in the Venn diagram showing support for various HDR formats by broadcasters and TV set manufacturers. There was special concern because some broadcasters, most notably NHK, BBC, Sky, DirecTV and Dish, broadcast HDR in the HLG10 format using the HLG EOTF.

On the other hand, many television set makers, including JVC, RCA, Hitachi, Magnavox, Insignia, Westinghouse, Polaroid, Sharp, TCL and Philips support only HDR10 or Dolby Vision and the PQ EOTF. What happens when a HGL signal reaches a PQ TV? It’s not pretty (literally). TV brands that support both HLG and PQ, like Samsung, Hisense, Panasonic, LG, Vizio, Funai and Sony, will have fewer problems with HDR.

The final speaker was Mark Schubin, the perennial iconoclast. Since, in general, I agree with him, I especially appreciated his talk. One of his points was a point he has made many times before: TV set makers, broadcasters, SMPTE and content creators are focusing on human factors issues that are hardly visible to the average viewer. These include HDR, wide color gamut (WCG) and higher resolution like 8K and 4K. HDR, in particular, is only really visible under carefully controlled viewing conditions like Dolby Cinema or a high-end home cinema installation in a dedicated and well-darkened room. Don’t expect to see any benefits of HDR when watching TV on your smartphone or laptop on the way home from work.

These groups are ignoring human factors issues that are clearly visible to even average viewers, especially high frame rate. The reason for this is clear: HDR, WCG, 8K and 4K are relatively easy and cheap to implement at the standards, content creation and display levels and do not significantly increase the bit rate if done correctly. On the other hand, it is much more difficult to go to higher frame rates without significantly increasing both the bit rates and the cost of everything from content creation through the TV display.

Higher resolution such as 8K or 4K in fact goes the wrong way by effectively reducing the frame rate in order to keep the bit rate under control as I discussed in my earlier DD “Can We Tell Stories With 8K?” This frame-rate issue leads to the problem that 8K resolution at 24 or 30 frames per second is really only visible when there is virtually no motion in the image. One of the comments on my 8K DD was that even 120Hz isn’t a high enough frame rate for 8K: at least 240Hz was needed to avoid motion blur.

When was the last time you saw lots of motion in a 4K or 8K demonstration signal provided by a TV set manufacturer? The most common demo content I’ve seen is very, very slowly panned scenes of absolutely gorgeous, colorful and detailed landscapes.

In general, the speakers agreed that HDR is (or could be) a good thing for the viewers. What they all emphasized was the practical (but solvable) problems on the road to widespread adoption of HDR. –Matthew Brennesholtz