I see three significant problems with virtual reality (VR) in today’s world: creation of VR content, distribution of VR content and display of VR content. My previous Display Daily dealt primarily with distribution of VR content and this one will look at the production of the VR content.

On September 21, SMPTE hosted a webcast presented by Richard Mills, Technical Director, of the Sky VR Studios. He says he has been shooting VR content for three to four years now, representing several hundred VR shoots. I suspect this puts him in the top tier, in terms of experience, of VR content producers.

Sky VR’s Technical Director Richard Mills (Credit: Sky VR)

Sky VR’s Technical Director Richard Mills (Credit: Sky VR)

Sky VR launched its VR app in 2016 and it’s currently available on both Google Play and in the Apple Store. If you’re using a Gear VR or Oculus Rift headset, you should download the app from the Oculus store. When Sky launched the VR app, they had 26 pieces of content available and they now typically have about 40 pieces on-line at any given time. Of these 40, typically about 20 were created in-house at Sky VR, 3 or 4 were commissioned and 16 were acquired from independent content creators. About 70% of these content pieces are 2D while 30% are 3D. According to Mills, Sky is creating two new pieces of VR content per month, typically one major piece and one more modest piece. These pieces are all 3DOF VR, that is the viewer can control which direction he can look (360° video) but the content producer controls the motion of the center of the field of view.

Mills said Sky is producing VR content for five Sky UK genres: Sky Sports, Sky Arts HD, Sky News, Sky [Entertainment], and Sky Cinema. All these genres will be available through the Sky VR app. Virtual Sky will also be providing 5 – 30 second VR advertisements to accompany VR content both on the Sky app and other VR platforms.

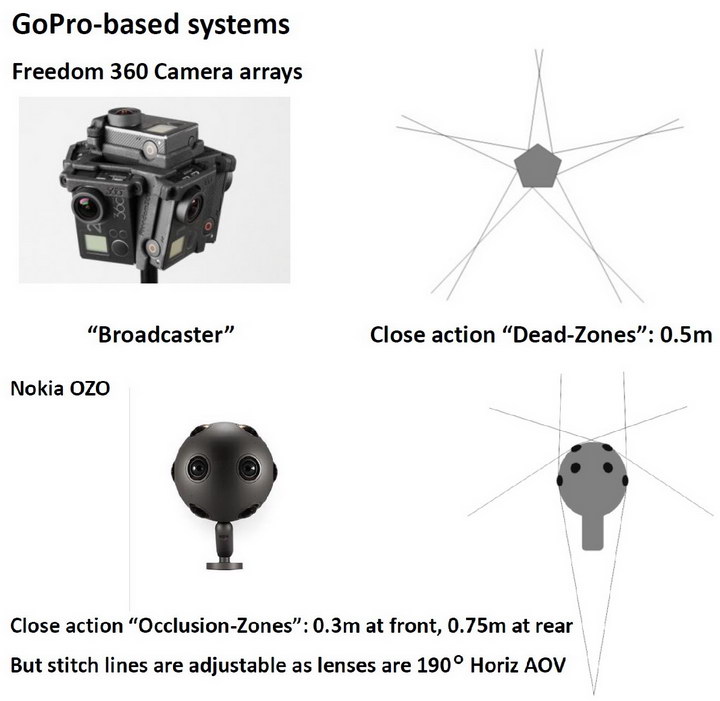

Mills started his talk with a discussion of 360° VR cameras, with caveats for those new to VR content production. Many starting VR producers use arrays of compact cameras, most commonly from GoPro. These arrays can have anywhere from 3 to 14 cameras in them and can be either 2D or 3D. He warned that overheating can be a problem in these arrays, especially during battery charging. Low temperatures can also be a problem since this can dramatically reduce battery life.

Camera dead zones. Top: a six-camera array of GoPro cameras. Bottom: A bespoke VR Nokia Ozo camera that is asymmetric front to rear to match human perception. This provides different front and rear dead zones. The Ozo camera mount is below and to the rear, putting it inside the dead zone so it is not imaged. Note: Citing “slower-than-expected development of the VR market,” Nokia has announced a sudden stop on its Ozo 360° VR camera development although existing customers will continued to be supported. (Images: Sky VR)

Camera dead zones. Top: a six-camera array of GoPro cameras. Bottom: A bespoke VR Nokia Ozo camera that is asymmetric front to rear to match human perception. This provides different front and rear dead zones. The Ozo camera mount is below and to the rear, putting it inside the dead zone so it is not imaged. Note: Citing “slower-than-expected development of the VR market,” Nokia has announced a sudden stop on its Ozo 360° VR camera development although existing customers will continued to be supported. (Images: Sky VR)

Other camera types he discussed included arrays of professional cameras, twin lens cameras for low end and amateur applications and bespoke camera arrays for 360° video acquisition. Issues with all camera systems include topics familiar to creators of normal content such as gen-locking multiple cameras, recharging, camera control, which OETF to use, etc. One factor not normally an issue in conventional content is that every camera array design has a minimum distance between the camera and the subject. This occurs because there are dead zones between cameras close to the camera array. If the subject ventures into this zone, the image is simply not captured and if it is close to the dead zone, stitching the multiple images together into a single 360° image can be difficult.

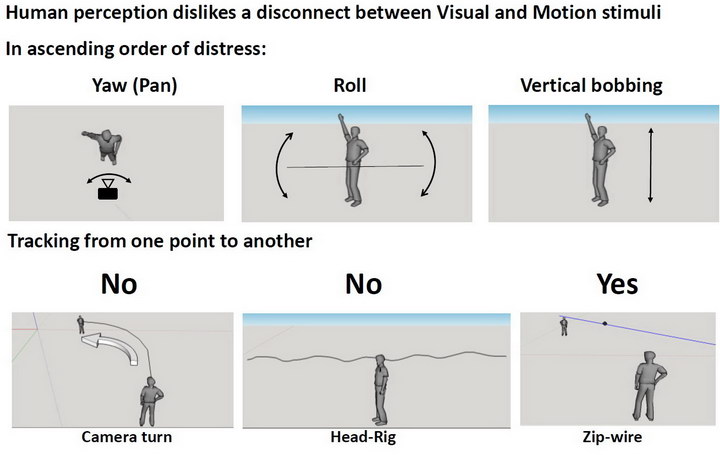

Camera motions Mills did and did not recommend for 3DOF VR content (Credit: Sky VR)

Camera motions Mills did and did not recommend for 3DOF VR content (Credit: Sky VR)

VR sickness is a major problem for the VR industry. One good way to minimize it is to have no motion of the camera at all. To tell the desired story, this isn’t always possible and Mills gave camera motions that were more likely to cause VR sickness than others. While panning the VR camera is possible, it rarely is necessary. Instead, the VR experience should provide the needed cues via audio or peripheral vision to the viewer to make him turn his head in the desired direction.

Rolling the camera is undesirable because it tilts the horizon. Again, this is best done by the viewer, not the camera man. If there is roll or tilt in the content, as there often is in VR content shot from drones, it should be removed in post production. Vertical bobbing is just a no-no: don’t do it. If camera motion is necessary, it should be in a straight line, e.g. via zip line, and the motion should not be combined with a pan or camera turn.

After discussing VR cameras and VR camera operation, Mills went on to discuss two VR videos he has created for Sky The first was for Sky Sports and involved David Beckham, football (soccer) legend and Sky Sports spokesman, introducing a variety of sports in VR format. The second was a portion of the ballet Giselle, then the talk of London society, with dancer Tamara Roja. The funny thing is that after his long discussion of VR cameras and VR camera operation, VR cameras did not play a major role in either of these productions. Instead, the subject was shot using more conventional cameras and then composited into the 360° VR background in post-production. David Beckham was shot in 2D against a green screen using a Sony F55 camera in portrait mode, making this compositing relatively easy.

David Beckham was shot against a green screen. Since he had to move among real objects in the final VR video (e.g. a pit stop for a F1 Grand Prix car), his motions needed to be very carefully scripted. (Image: Sky VR)

For Giselle VR, which was done in 3D, a green screen could not be used because this hid all the visual cues Tamara Roja needed to do her dance. She was captured not with a VR camera but with a conventional mirrored 3D cinema rig. The only concession to VR was the camera rig mount – it was mounted so any pan or tilt of the camera rig rotated the camera about the center of the image generated. This eliminated parallax problems as the camera followed the dancer.

3D camera rig and production crew used to acquire the dancer’s image for Giselle VR (Credit: Sky Arts)

3D camera rig and production crew used to acquire the dancer’s image for Giselle VR (Credit: Sky Arts)

During the video shoot of Roja, it was not necessary to clear the set of all personnel since the camera was only acquiring the image of the dancer and the walls directly behind her. Since they couldn’t use a green screen background, they recorded all the camera motion pans and tilts and then, after clearing the set (an old industrial building) acquired the background empty of Roja and production personnel alike. For the background acquisition, the VR camera was on a motion base programmed to match all the pans and tilts used to acquire Roja. This greatly simplified the compositing of the dancer with the background. Of course, then the pans and tilts in the 360° image were all removed in post-production. One advantage of this process is it was never necessary for a stitch line to pass through Roja or the background directly behind her.

Post production is of critical importance to VR, especially professional-grade VR of the sort Sky wants to provide for its VR app. Mills said post production was similar to post production for other video forms and it has additional steps of its own. For example, VR rushes for on-set use are made with automatic image stitching but for the final product stitching was redone in post with a semi-automatic process. This not only provides a better stitch but also allows the person in post to move the stitch line so it doesn’t pass through critical objects such as actors.

Mills also discussed quality control used on VR content, whether it was in-house, commissioned or acquired. The content was typically 4096 x 2048 resolution with a 2:1 aspect ratio (when shown flat), 10-bit, 4:2:2, progressive 25 to 120fps. Sky would accept VR content in MXF, IMF, DnxHR HQ or ProRes 422 HQ format. Audio was preferably Spatial WXYZ 3D audio but Sky would also accept 5.1 or stereo audio as well. The first QC step was to examine the files digitally to ensure they matched all the required video standards, in a process similar to the standards-conformance checks done on non-VR content. In addition, both computers and humans watched the content, looking in particular for parts of the content likely to induce VR sickness. He said that (so far) Sky has not rejected content based on its ability to induce VR sickness. Instead, they rate the potential from mild to severe and warn the viewer about this potential.

Audio, especially 3D audio provides a new problem for VR content. Like all audio, of course, it must be synchronized correctly to the video. 3D audio in a VR application must also come from the correct direction. For example, when a viewer turns his head to look at a singer to his left side, not only the video but the audio must change so the sound is coming from directly in front of his turned head.

Mills’ complete 1 hour 41 minute webcast is streaming on-line to SMPTE members Here. The PDF of the slides he used is also available. –Matthew Brennesholtz

Analyst Comment

As can be seen, making good VR content is not easy. The alternative, I guess, is making bad VR content that quickly bores viewers, induces VR sickness, or both. MSB