Why Am I Writing about Sound in Display Daily? – The quick answer is: Sound keeps coming up in a display context.

Of course, sound has accompanied moving images in developmental systems since the early 20th century, and the Bell Labs/Western Electric Vitaphone sound-on-disc system gave Al Jolson a voice in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature-length talkie. That system was quickly replaced by sound-on-film, in which the sound was encoded as an optical signal which exposed a separate track on the motion-picture film, guaranteeing a sound track that stayed synchronized with the moving picture. And even with digital video and audio replacing optically exposed tracks on film, and even with the number of audio tracks increasing, the concept remained roughly the same: Audio channels synchronized with the video were amplified and directed to separate speakers, with each channel always playing through its dedicated speaker (or speakers).

About 20 years ago the British company New Transducers Ltd (NXT) introduced the Distributed Mode Loundspeaker (DML)*. Initially, the idea was to place a small transducer or transducers on a flat panel and drive it in such a way that different vibration modes were distributed across the panel. The technique could be used to produce a wide frequency range with a simple structure, and different sound channels could emanate from different portions of the flat panel– stereo from one physical speaker. Clever. But if any planar material could be used to make a DML, why couldn’t that material be the front glass of a display? By integrating the physical structures of display and speaker in a laptop PC, for instance, designers could solve the problem of not having room in a PC for decently sized (and decent sounding) speakers, and could reduce weight and complexity.

Alas, “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley.” (Robert Burns)

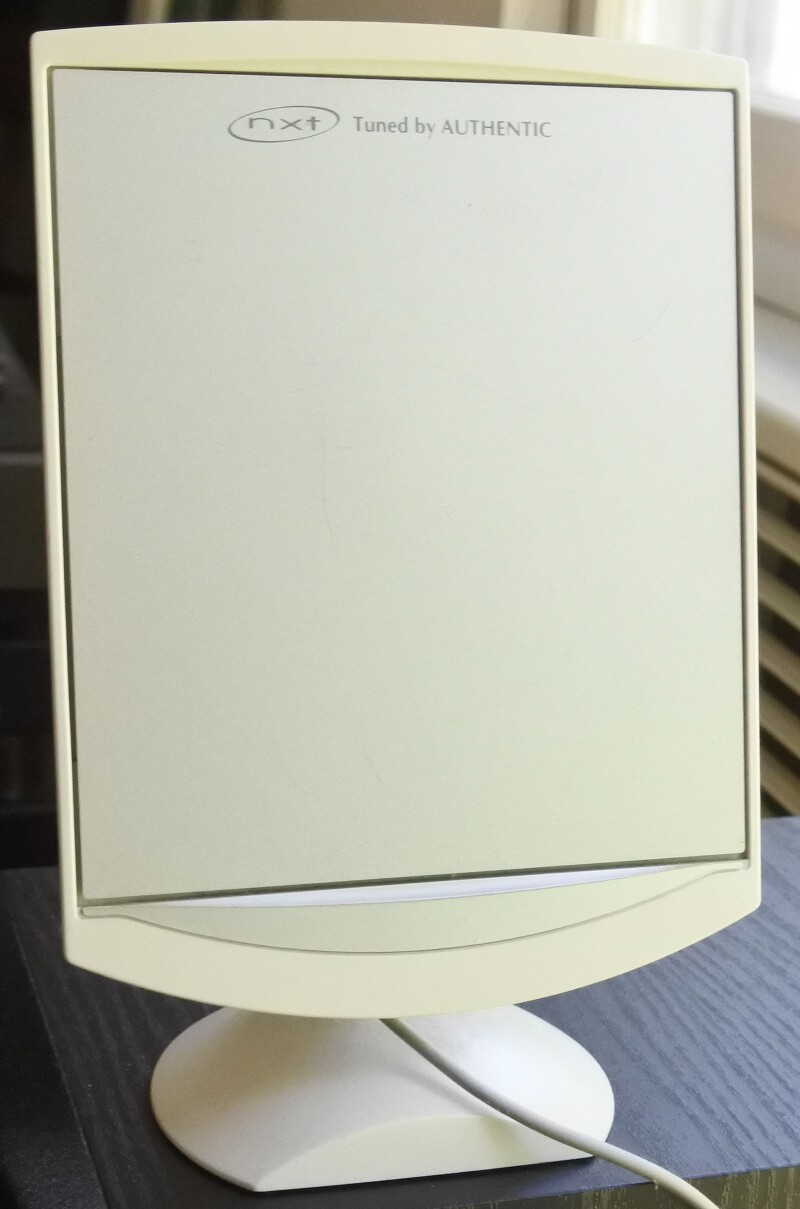

It turned out that when the panel was vibrating a lower acoustic frequency, it created visible interference artifacts with the panel’s optical structure. NXT solved the problem by blocking audio frequencies below 150 Hz (if memory serves), but that required the addition of a woofer, and the overall attractiveness of the DML system for displays was significantly reduced. Still during the company’s lifetime, it produced quite a few NXT speakers. Sitting on my desk right now is a 2.1 system that was originally packaged with an NEC desktop computer. It has a conventional little powered woofer and two smallish NXT speakers. Sounds pretty good.

A DML-like technology has made a recent and heavily promoted appearance as LGD’s Crystal Sound OLED panels. In the best implementations, the sound emanates from close to the point on the screen as the image that produces it. (Sony also has a similar system – Man. Ed.)

More Dimensions is Better

Even better is doing that in three dimensions, which is the point of object-based surround sound sytems such as Dolby Atmos. Here, two or four height speakers are added to the typical 5.0 (left, right, center, and surround left and right speakers) or 5.1 (as above, but with a powered sub-woofer added. Adding the height speakers makes it a 5.0.2 or 5.0.4. (or 5.1.2 or 5.1.4) system. A 5.1.4 system requires 9 channels of ampliication and nine speakers, plus the self-powered woofer. But in addition, the system places a limited number of sonic objects in your viewing room’s three-dimensional space, and moves them around as the Atmos sound encoding instructs it to do. So, a helicopter can approach from the horizon at front right, fly overy your head, and drop supplies right behind you with a thud. The sound is, of course, coming from your seven or nine speakers, but the sonic objects are positioned independently of what the audio channels are doing otherwise. So, we have a closer spatial coupling between the video and audio than we have ever had before in a consumer product.

At this point, I’m reminded of the old TV salesman’s saying from the CRT days: “The way to make a TV picture look better is to hook the set up to a big speaker.”

It was recently announced that the keynote speaker at this autumn’s SID Vehicle Displays and Interfaces Conference (Sept. 25-26, Livonia, Michigan), will be Kristin Kolodge, Executive Director of Driver Interaction and HJMI at J.D. Power. Her topic is “Voice of the Customer: Displays as Trust Enabler.” One point she will make is what is important is not only what the interface displays and says, but also the voice in which it says what it says. Makes sense of course. It would be hard for an owner to trust his or her car if it spoke with an accent that did not inspire trust and even affection.

Smart TVs and set-top boxes increasingly accept voice commands, while Google Assistant and its less capable competitors have been using AI-based voice recognition for some time.

So, increasingly, the human-machine interface is multi-modal. The Vehicle Displays Conference has embraced that reality with enthusiasm, and automotive OEMs and tier-one suppliers have responded in kind, giving Vehicle Displays and its exhibition impressive growth. It is not in our best interest to artificially separate the technologies of the senses and say we only want to think about the technologies that deliver images.

It’s the system, baby! Anyone for smell-o-vision? – Ken Werner

* Display Monitor has been reporting on this technology since it was discovered by V-Labs in 1996 (Display Monitor Vol 3 #40) and by 1998, the company had 50 licencees including NEC’s speakers that Ken has at IFA (Display Monitor Vol 5 #39). It is also being developed for smartphones by Redux which has added haptics to the NXT concept. Ken also reported on an electrostatic approach shown by Turtle Bay in SID’s Display Week Innovation Zone in 2017. (BR)

Ken Werner is Principal of Nutmeg Consultants, specializing in the display industry, manufacturing, technology, and applications, including mobile devices, automotive, and television. He consults for attorneys, investment analysts, and companies re-positioning themselves within the display industry or using displays in their products. He is the 2017 recipient of the Society for Information Display’s Lewis and Beatrice Winner Award. You can reach him at [email protected].