I just got time to decompress after Display Week and an extended tour of the tech companies of the USA and EU and think about how different things are for companies that are not yet in the heart of AR innovation.

A year ago, smart glasses still felt like a curiosity, cool in theory, clunky in practice. Now they’re being talked about as the interface for the next wave of AI.

Think of a use-case, let’s say you just got Smart Glasses, and you’re packing for an overseas trip, and your smart glasses pipe-up –

“Hey Peter, you forgot to put your passport into the bag”.

But the taxi is coming in 10 minutes, so you say,

“Hey Glasses, where the f*** is my passport”, forgive the bad language, but there is real pressure… and the Glasses say,

“Peter, you put the passport down on the desk two days ago, then you put an envelope on top”.

That is the sort of use case that you’d tell the taxi driver about, tell the person at airport check-in, tell the person in the next seat. They will be wanting them too, believe me.

And it’s not just hype from startups. Meta, Google, Qualcomm, Snap, and Sony are all aligned: smart glasses aren’t just getting a second wind, they will be essential.

There’s a growing recognition that to make generative AI useful in real life, it needs to see the world around you. Not just respond to prompts, but understand what you’re doing, where you are, what’s about to happen. That level of contextual awareness needs eyes and ears, in other words, a camera and microphone, assuming we aren’t yet ready to be followed around by AI drones, Iain M. Banks style.

Your phone’s in your pocket. Your watch can’t see. Smart glasses, by contrast, offer ambient input, spatial awareness, and, critically, on-device AI. Qualcomm already has demos running multiple models entirely on the glasses: full speech recognition, AI-driven search, and speech synthesis. No cloud required.

In the example above of the passport and the bad language, the Glasses are literally a save, but to make it work needs that AI device that can see.

The form factor still matters, though. Meta’s partnership with Luxottica gave them a head start by making smart glasses that look like actual glasses. That includes prescription lenses, which quietly turns optometry into a high-value retail channel for tech. Google seems to realize they missed a trick there.

It’s not just fashion. For mass adoption, smart glasses need to blend into life. When they look, feel, and function like your regular specs—but add a layer of intelligence—they start solving real problems. Helping you pack, translating speech, nudging you before you walk into traffic, reminding you where your wallet is. These aren’t moonshots. They’re being worked on today.

The industry view is converging: Gen 1 glasses use audio, Gen 2 add a display, Gen 3 builds immersion. Android XR is emerging as the OS standard, and the hardware stack is lining up behind it.

The phone isn’t going anywhere, but something deeper is shifting. If even 20% of people start skipping phone upgrades in favor of smart glasses on a subscription model, it changes the economics for companies like Apple and Samsung in a very real way.

This isn’t about novelty. It’s about a new interface for ambient computing, one that finally makes generative AI truly personal and useful.

What’s more is that the big-tech companies need training data for their AI, they can’t mine the internet for text (like with LLMs) they need live-use case data (so it can learn what a passport is, why it matters if it is lost, and learn to forgive the bad-language.

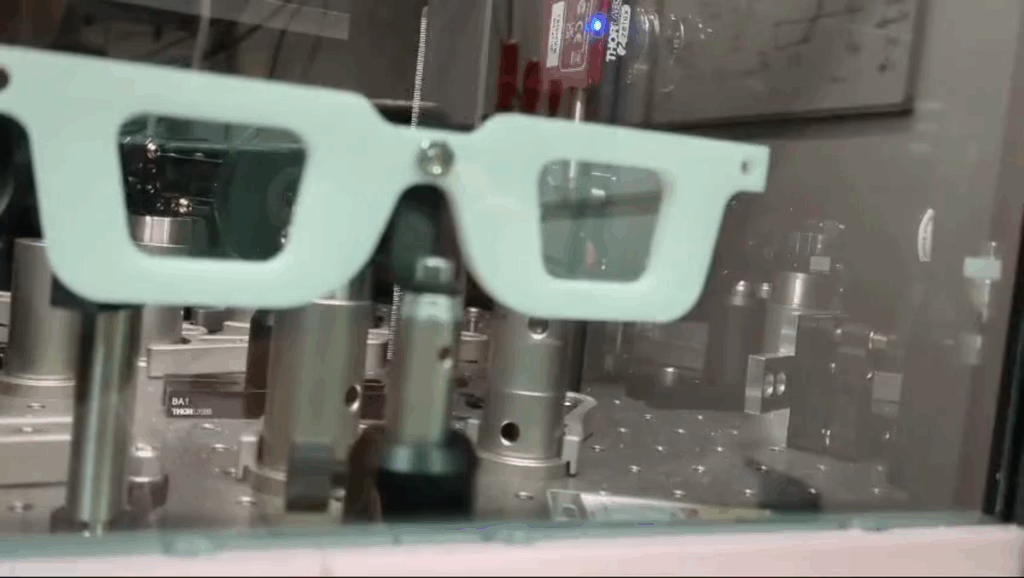

Peter G.R. Smith is a Professor in the Optoelectronics Research Centre and in Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Southampton. He graduated from Oxford University with a BA in Physics in 1990 and D.Phil in Nonlinear Optics in 1993. After a year spent as a management consultant he joined the University of Southampton. He is the co-founder of Smith Optical, an emerging startup from the University of Southampton that is developing a revolutionary new type of mixed reality glasses.