In late September CB Research published a report entitled “The Top 20 Reasons Startups Fail.” The top reason is shocking, but if you’re familiar with start-up creation, and particularly with the creation of technology-based start-ups, it’s not surprising.

So, let’s start off with a selection of the CB Research reasons for failure, look at the Statista infographic, and then cut a couple of display-related start-up founders some slack by acknowledging the significant extent to which success depends on dumb luck, even for the minority of entrepreneurs who actually do all the things right that are aren’t in their control.

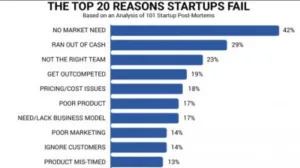

CB Research based its survey on 101 start-up post-mortems. The top reason for failure, cited by 42% of the failed companies, was “no market need.” What!? Do they mean entrepreneurs mortgage their homes, borrow from friends, redirect their kids’ college funds, and devote substantial talent and energy to develop technology and/or products for which there is no demand? Yes. Sadly, that is exactly what they mean. And those of use who have anlalyzed or consulted with start-ups cannot be surprised.

As many readers of Display Daily know, start-ups are often started to continue a founder’s university research or pursue an interesting technological problem or application. These quixotic endeavors are often justified with a generous dose of “If you build it, they will come.” But they don’t come.

The accompanying infographic supplies all of the top 20 reasons for failure, but let’s focus on just few of them. Being undercapitalized is #2, and that’s no surprise to anybody who has been through the process. But “not the right team” (#3), pricing/cost issues (#5), need/lack business model (#7), poor marketing (#8), and ignore customers (#9) are very much of a piece with #1. On these axes (and others), the failed start-ups did not take account of essential business requirements.

But even if you actually think of these requirements, success is not at all assured. Let us, very briefly, look at two display-related companies whose creators were not inept. One company had initial success and then failed because of a change in television architecture that would have been very hard to predict when the company was created. The second company developed an innovative technology that seemed like a “no brainer” (my assessment at the time) for for cost-reducing LCD displays. The market did not materialize, and the company almost folded, but an unanticipated application appeared ten years later, and just in time.

Example #1

The first company was the early quantum-dot innovator QD Vision, whose approach was to encapsulate their quantum dots in a thin cylinder that was placed in front of the blue LED’s in the LCD panel’s edge-light. At a time when edge-lighting was ascendent this seemed like a recipe for success. But the dominant TV set architecture quickly turned to full-matrix backlighting, and even the makers of most edge-lit sets favored the competing quntum-dot-enhancement-film (QDEF) approach. QD Vision had no sufficiently large place to go with its then current product and its development of electroluminescent quantum dots was not sufficiently advanced to save the day. The company’s technology was acquired by Samsung Display, whose primary interest seemed then and seems now to be in that electroluminescent QLED technology.

Example #2

The second company was Clairvoyante, Inc., whose founder Candice Brown Elliott invented the PentTle Display subpixel architecture. This architecute and its many successors permitted the fabrication of full-color displays with less than 3 subpixels per pixel. This increased luminance and resolution, while reducing power requirements. At a time when applications were pushing LCDs to higher resolution, PenTile indeed looked like that “no brainer.” I was so convinced that I helped institute the initial development agreement between Clairvoyante and Samsung, working only for stock options.

But the LCD industry took the “brute force” approach to higher resolution with the remarkable and sustained development of many more and much smaller pixels. The company survived on consulting and development work until Samsung, then in the midst of energetic development of small OLED displays, found it had an intractable problem for which a version of PenTile was the solution. Early OLED displays had a lifetime problem, but PenTile produced larger subpixels and reduced density for longer life. Samsung acquired the technology.

QD Vision had a reasonable solution until TV architecture changed, which was not readily predictable. Clairvoyante had a literally brilliant solution to a problem that the industry decided by brute force. A completely unanticipated application arose just in time to reward the original investors. My stock options were worthless, but I learned a valuable lesson and I made some very good friends. KW.

Ken Werner is Principal of Nutmeg Consultants, specializing in the display industry, manufacturing, technology, and applications, including mobile devices, automotive, and television. He consults for attorneys, investment analysts, and companies re-positioning themselves within the display industry or using displays in their products. He is the 2017 recipient of the Society for Information Display’s Lewis and Beatrice Winner Award. You can reach him at [email protected].