Although the SID’s DisplayWeek is slowly beginning to drift away to the past, there is still quite a lot to learn from the speakers at the DSCC/SID Business Conference. I always enjoy the talks by NPD’s Stephen Baker, who brings a great sense of reality to these events, based on NPD’s tracking of consumer electronics in the US.

While analysts, home cinema fans and technology companies get very ‘hyped up’ about the latest technologies and new trends, Baker’s experience and NPD data shows that for most people, TV is very much a commodity and what they expect to pay doesn’t change very much over time, even if there are exciting technologies around.

An Early Lesson Learned

That was a lesson I learned very early in my days as an analyst. After around 12 years in the monitor industry, I thought I had a good understanding of it when I founded Meko back in the mid-90s. Around 2000, we started a market research service that looked forward rather than just tracking history and once we had a few quarters, I was chatting with my business partner and another monitor veteran, Pete Gamby, about the data we were supplying. “Pete”, I asked. “Have we done an ASP chart for monitors over time?”. It turned out we hadn’t so we did one.

But there was something wrong. We had ‘known’ that the ASPs for monitors were continually going down. After years in the industry, we understood the huge pressure to drive down the prices for CRT monitors. Yet the chart that we created showed a flat line. We spent a couple of days going through all the data to see what had gone wrong, but nothing was wrong. We had good street pricing data collected by a fantastic team who took huge pride in their accuracy. It was all well categorised and we applied that data by brand, segment and country across Europe. We were getting reported data from 75% to 80% of the market, so there was a huge amount of input data.

So we thought about it. What did it mean? In the end we realised the importance of price positioning for buyers. Once a buyer has an idea of ‘what a product should cost’ or ‘what is reasonable to spend on this kind of product’ it can be very hard to change that. I thought back about my own experience as a buyer.

How Much is a Computer?

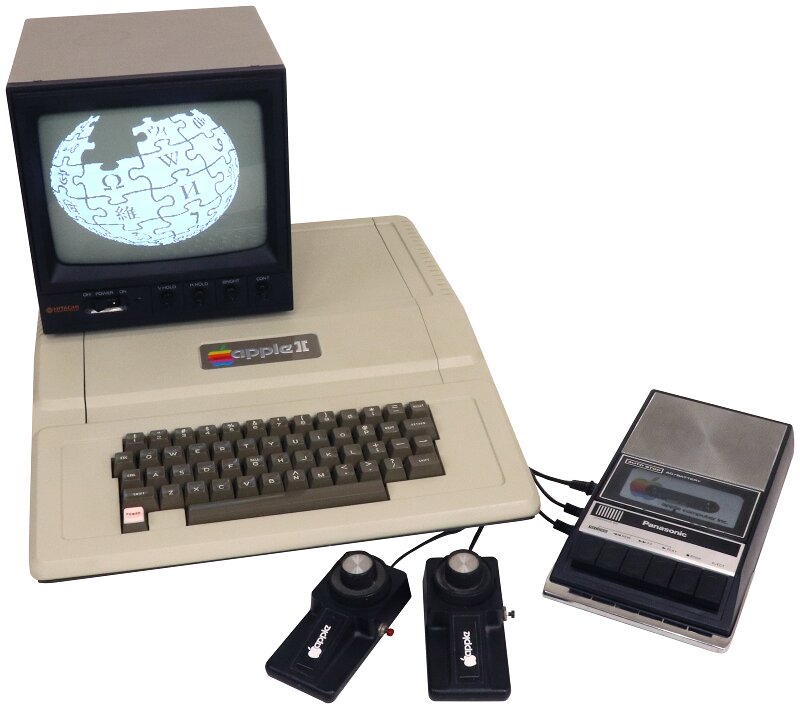

I had been buying computers since around 1980 (I must check – I’m sure I still have the invoice for my Apple ][ somewhere!). It cost somewhere around $1,500, a lot of money to me at the time. It turns out that 40 years on, $1,500 still seems a reasonable price to pay, to me, for a good computer. Of course, what you get for the money doesn’t bear comparison with what you got then. My precious Apple had a 1MHz clock, 8 bit CPU, 16K of RAM, no hard disk, only monochrome low resolution graphics and was mains powered. I added new ROMs, some wire and a clip to enable lower case text! My latest 2019 ThinkPad is a different beast, altogther.

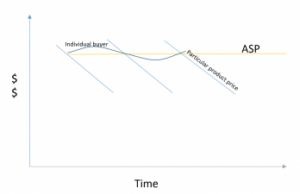

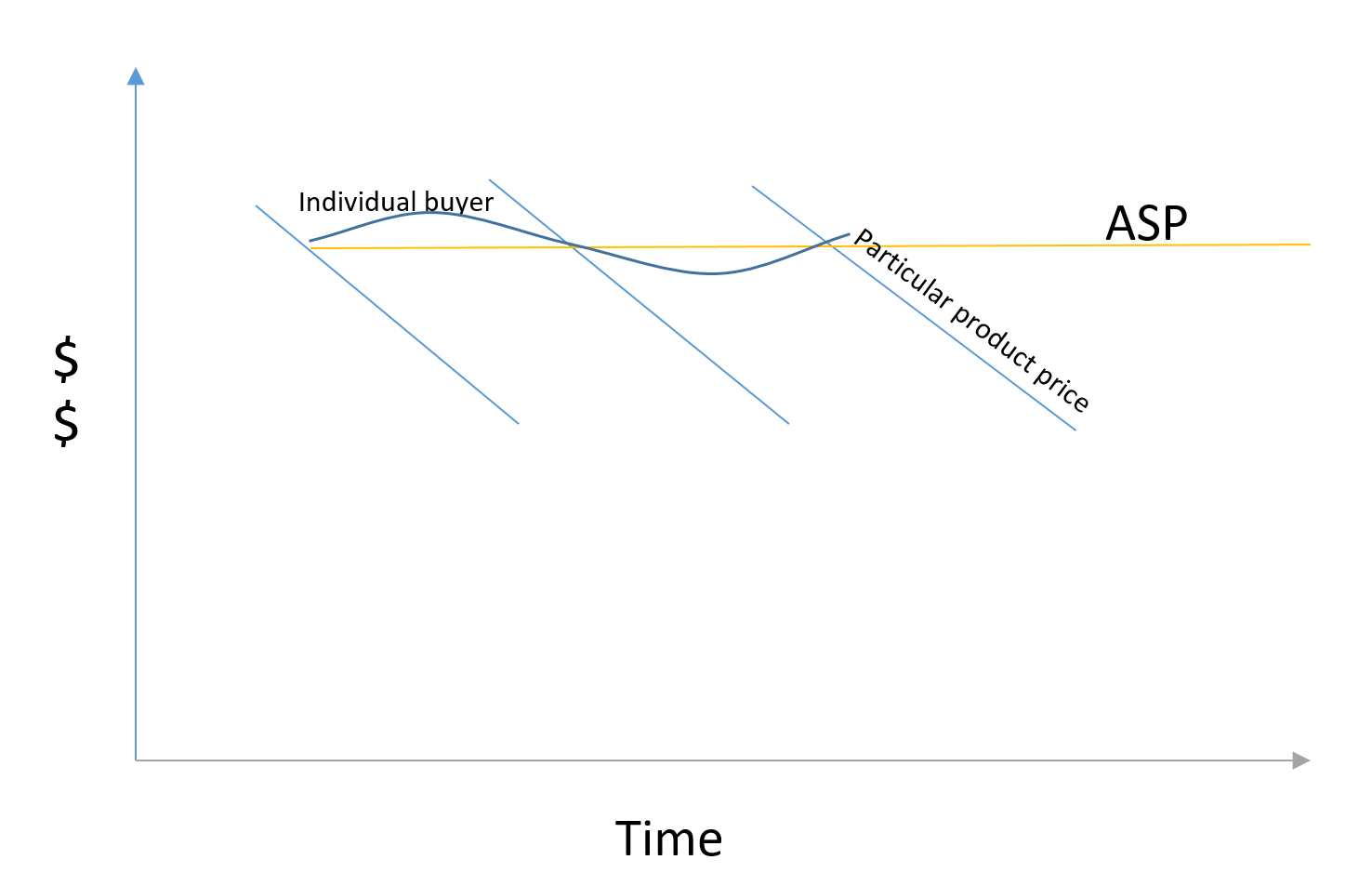

So what I realised is that buyers often have a price in mind that is reasonable to them for a class of product. Providing you keep delivering better value, buyers, whether consumers or commercial, will usually have an idea of what they feel it reasonable to spend. So while the price of a particular product might fall, the ASP is much more stable.

Although the price on each generation of product might fall, buyers will jump to the next product if they are sure of the value, maintaining ASPs.

Although the price on each generation of product might fall, buyers will jump to the next product if they are sure of the value, maintaining ASPs.

That understanding really helped me develop a good forecasting methodology for the LCD market. I would listen to the forecasts from panel makers, which were always aggressively tipped towards moving more and more buyers to larger and larger panels. The reality was that, in the short term, there are a limited number of buyers at a particular price point, so there is a limited pot of money available to pay for new products.

I used to feed the numbers into my models. These always showed that if the panel makers were correct, the value of the market was going to rise, and ASPs would rise. The panel makers were optimistic about this because they were investing heavily in new factories. However, I knew that ASPs would not rise, if the patterns of the past were going to continue.

Supply-Side Driving

The panel industry has always been very supply-side driven. Once a panel maker decides to build a fab, the key thing for them to do is to get costs down. To do this, they have to get yield up, and the only way to do that is to go up the learning curve and make panels. So, once a panel fab arrived, it was going to supply making the supply ‘inelastic’ – it was going to happen regardless of demand. On the other hand, we had established that at a particular price point, demand was pretty inelastic. That meant only one variable – price.

This understanding allowed me to forecast that panel prices were going to have to fall if the panel makers were to supply what they intended to. However, the real value was in knowing when they would fall. So we started tracking inventory of monitors with a simple monthly report from the brands in the market. At that time, Europe was a big market for monitors, and that was a key application for absorbing panel supply. When inventories started to rise, we knew that brands would reduce their ordering, but panel makers would want to boost supply, so prices had to fall.

We actually got our forecast right a couple of times, although the level of price drop was always more than we forecast. I had a couple of clients who understood what we were doing and paid attention. They did very well out of it, by clearing their inventories and then buying new products once the price had fallen, while other clients, that didn’t believe we could forecast it, were left with inventory that they had bought at the high price. One client said to me once “You know, I’d be happy to give our purchasing department an order that says ‘give Bob the money he wants, some years he tells us something really important'”. Of course, that never happened – we always had to provide a lot of reports, data, services etc to earn our money.

I remember one phone conversation with a big and irritated panel maker

“How can you couple of people in Europe forecast this? The other analysts [no names] are not forecasting it. You must be wrong!”.

My answer was not complicated,

“Simply, there is not enough money in budgets for people to buy the products you want to sell at the price you want to sell them”

I learned later that the bigger analysts really couldn’t be so aggressive in their forecasts. I was at SID one day when Barry Young, then working with DisplaySearch, was asked “If TV demand and monitor demand really slackened, would panel prices fall?”. Barry carefully gave an answer that in those conditions, which, he explained, were not the current conditions, that would indeed be the result. However, in translation to the headlines in the financial press his answer became “Panel Prices to fall according to analyst”. As a result, a huge amount was wiped off the market valuations of some panel makers, which were key clients and collaborators for his firm. That was another lesson learned.

Anyway, back to pricing. the other side of the same coin was that panel makers often drove down prices faster than they needed to, and that’s a topic that I’ll return to in another Display Daily, shortly.

Oh! I seem to have not written about what Stephen Baker said about the TV market, so I’ll continue with that later this week. (BR)