Over the last couple of weeks, there have been a couple of articles in our press releases that highlighted the use of Pixelworks technology in smartphones from TCL and OnePlus. Just before the first of those releases, I had the chance to catch up with the firm to get some background to its latest technology.

When the press agent contacted me, the plan was to start with an ‘introduction to Pixelworks’. I had to point out that I first reported on the firm not long after it was founded (by execs of In Focus) in 1997 when it was the distributor of Fujitsu plasma displays in the US. I first interviewed the company the next year at SID (I vaguely remembered that the firm was in a caravan in the car park of SID, but that may have been another firm). By then, the company was positioning itself as a fabless chip company that was solving some display interface and format issues for projector makers, in particular.

By 1999, it was offering chips optimised for monitors as well and it had a good name for quality. In 2001, Display Daily’s friend, Dr Ray Soneira of DisplayMate Technologies gave the Pixelworks chips an award for being the best image processor. TV was added to the target markets. It was due to merge with Genesis in 2003, but it was called off. Over the years, the firm bought a number of other chip companies including Vixs which had a great reputation for format transcoding and other processing, in 2017. However, profits were often difficult to come by in TV and in 2006, the company suffered major financial discomfort after writing off a lot of goodwill from these purchases.

At CES 2010, I reported on the firm’s ME/MC technology, a key technology for the firm over the years. At CES in 2013, I saw the latest 4K chips, which were said to be in a number of TVs at the event, but they weren’t named and the company was struggling to compete with the biggest TV chip vendors and losing money again.

A Pivot To Mobile

That caused a pivot and by 2014, at CES the emphasis was on how the firm’s video technology could be used in low power applications such as smartphones. The company highlighted how clever colour and contrast management could maintain image quality without increasing power consumption. In 2015, Ken wrote a Display Daily (Pixelworks Improves Mobile Display Quality While Reducing System Cost) about the firm’s Iris mobile processors. We also reported that the firm had software as well as hardware solutions for smartphones. By 2016, it had some wins with Asus and others, but losses were still an issue.

In 2017, we announced the Iris third generation mobile processing chip. In 2018, we reported wins with Xiaomi and ZTE.

Now the company has wins with TCL and OnePlus. Overall, we’ve reported on the firm almost 400 times! So, we skipped the company introduction….

(although, in discussions, we heard that technologies for content creation are now a significant technology area for the firm, now, so that’s a topic I’ll return to another time!).

Iris Technology

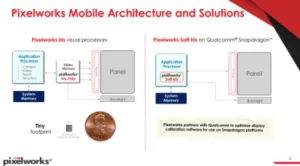

The Iris technology is available in a dedicated processor (with its own memory for ME/MC) or as software, and the Iris technology is used in a partnership with Qualcomm on SnapDragon processors. While the technology can optimise things for the maker in terms of performance, power and cost, for the smartphone user, there are visible advantages in motion, colour performance and image clarity. The technology reduces the visual artefacts that are often seen in video sent to smartphones, but without destroying the artistic intent.

HDR is gradually becoming more and more important and the company can upconvert SDR content to HDR both for video and gaming (there is little native HDR content available, yet). That means that users can enjoy an ‘Always HDR’ experience. Dual MIPI channels can be used to support 4K video and also 120Hz frame rates. OnePlus is using the Iris chip.

Ray Soneira has been very impressed with the performance of OnePlus smartphones (e.g. The Beginning of the End – or Just the End of the Beginning?) and his review of the OnePlus 8 Pro. One feature of the performance that stands out is the colour accuracy and grey scaling and Pixelworks told us that one reason for this is that every phone is individually calibrated during production. Typically, this can take three or four minutes using most technologies, making the process uneconomic, so it is not done. However, using the Pixelworks technology, this can be reduced to 30 seconds, making it feasible.

A second area that the firm highlighted is that after the years of development, the company can be very sophisticated in its ME/MC. A critical point is that the firm’s algorithms can distinguish between video and graphics and can process each separately, significantly reducing the artefacts in each type of content. This can be done on sections of the image, not just the whole image, a feature that becomes more important as time goes on and content on smartphones gets more sophisticated and video-based.

The processor is said to be especially good at dealing with differences in frame rates between content and displays and this technology is a key element of its content creation Truecut technology.

Finally, Pixelworks highlighted how its processing can optimise content to look good regardless of ambient conditions when it has access to data on ambient lighting conditions. (It also told us about its current management for PWM backlighting to avoid flicker – but this DD is long enough!) (BR)