Compression has become an integral part of our world. We compress video and audio. We compress color resolution to save luminance detail. We compress photos to send over the Internet. We compress digital cinema files for distribution to movie theaters. Our editors compress deadlines on us constantly. (Okay, maybe that last one doesn’t belong…)

If you look at the complete production chain from camera to display, the only thing that hasn’t been compressed is the display interface signal. That is; until 2014, when the Video Electronics Standards Association (VESA) announced Display Stream Compression.

DSC, which is an entropy-based codec, is considered to be “light” compression. (Like when you board a crowded bus, tram, or subway car, and everyone scoots just a bit closer so the door doesn’t close on your arm.) DSC can compress a digital display signal (think DisplayPort1.2/1.3/1.4 and HDMI 2.1) by a factor of at least 2:1 and as much as 3:1.

That may not sound like much, but if you are trying to sample and encode a 4K DisplayPort signal – say, 2160p/60 with 10-bit RGB color, or 21.6 Gb/s uncompressed – 3:1 compression will lower the bit rate to the point where you can easily slide through a 10 Gb/s network switch, and with near-zero latency of just a few picture lines.

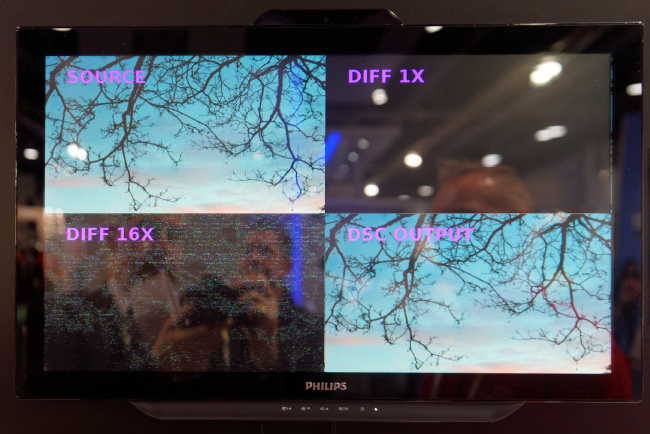

Hardent showed this demo at CES in 2016 – with compression differences multiplied by 16 to make them visible! Image:Meko

Hardent showed this demo at CES in 2016 – with compression differences multiplied by 16 to make them visible! Image:Meko

DSC works so well that it’s now the basis of the Blue River NT technology for AV/IT signal distribution that is being promoted by Aptovision (now part of Semtech) and the Software-Defined Video over Ethernet (SDVOE) Alliance. You’ll see plenty of their member companies at InfoComm in Las Vegas next month.

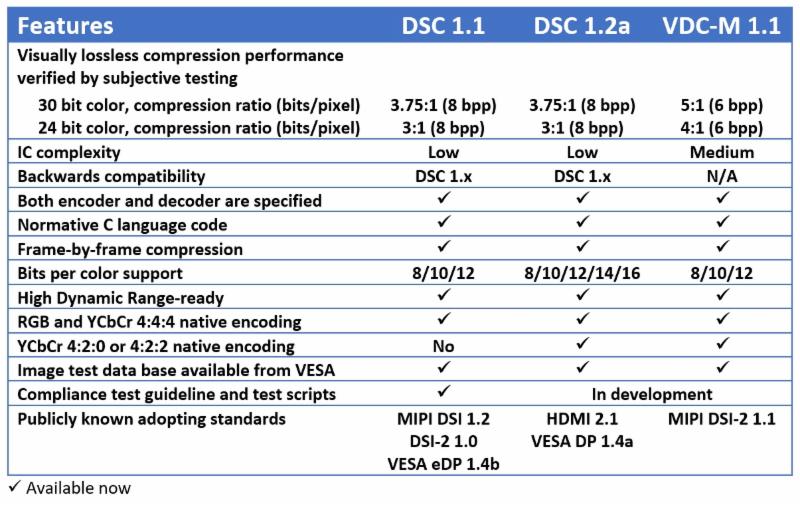

To date, I haven’t seen any other manufacturers pick up on DSC (although V1.2 is part of DisplayPort V1.4 HBR3 and – whisper it quietly – DSC 1.2 is part of HDMI 2.1 – Man. Ed.). But VESA isn’t sitting on its hands: Yesterday, they announced the VESA Display Compression-M (VDC-M) standard, which is intended to be used with embedded mobile display applications only. Unlike DSC, VDC-M has a maximum compression ratio of 5:1 for “visually lossless quality,” according to their press release. The trade-off? “Higher circuit complexity.”

This chart shows the differences between DSC 1.1, DSC 1.2, and VDC-M.

Note – table was corrected by VESA after publication. This is the correct version.

Note – table was corrected by VESA after publication. This is the correct version.

VESA claims that, starting with a 30-bit image, VDC-M can “enable compression down to 6 bits per pixel using a compression ratio of up to 5:1 while maintaining visually lossless viewing with no attendant loss of bandwidth.” But that requires a more complex driver IC.

The press release, (VESA Publishes Display Compression Standard for Mobile Applications), says that VDC-M will give mobile device designers a lot more flexibility in working with displayed images. They could increase resolution and/or color bit depth using the same display interface or reduce power consumption by lowering the clock rate. VDC-M could also reduce the size of frame buffers for video memory and simplify wiring and connectors.

Not surprisingly, Aptovision’s next-door neighbor in Montreal, Hardent, has already announced they will make available VDC-M encoder and decoder IP cores at some point in the near future, complementing their existing offerings of DSC IP cores.

If you haven’t yet seen a demo of DSC but are planning to attend Display Week, you might want to check out a presentation by York University on Friday May 25 in Session 85 (Image Quality), titled “Visually Lossless Compression of High-Dynamic Range Images: A Large-Scale Evaluation,” which evaluates the VDC-M and DSC standards at several compression levels for HDR image compression.

Now, all we need is a way to compress the physical display (fold-up OLEDs, anyone?). That could be handy when traveling on those crowded subway cars….

Analyst Comment

Subscribers to our newsletters will have seen our report on the development of this version of DSC from our MWC report and can see all our extensive coverage of DSC over recent years here. The topic of light compression has been a subject of interest here – whether DSC, the Tico version from Intopix that is now spreading in content creation and broadcast and the Lici technology that both form part of the JPEG-XS Mezzanine compression technology or the VC-2 codec (based on the Dirac research by the BBC) that was adopted as a set of SMPTE standards and implemented by Silex Inside (recently spun out of Barco).

If I remember correctly, both Tico and Lici were considered for proposal to VESA when DSC was developed, but after the decision to go a different way, they have been refined for video rather than display use. (BR)