This week past, marked the 50th (golden) anniversary of humanity’s first venture beyond our home planet with the successful landing of Apollo 11 on the surface of the moon, and the safe return of its precious human cargo – (along with a sack of rocks.) For many, that single human achievement defines the 20th century for all its good and ill, with lasting and deep effects that touches practically every living human on the planet today.

We’ve all heard of the fractional computing power those “right stuff” fly-boys took to the moon, (and reckoned by one writer Charles Fishman in his “One Giant Leap” book as 0.000002 of one per-cent of the computing power in today’s smartphone – yikes!) OK, here are the specs: 1MHz clock, four 16-bits registers, 4K RAM, and 32K ROM—using 1960s components.

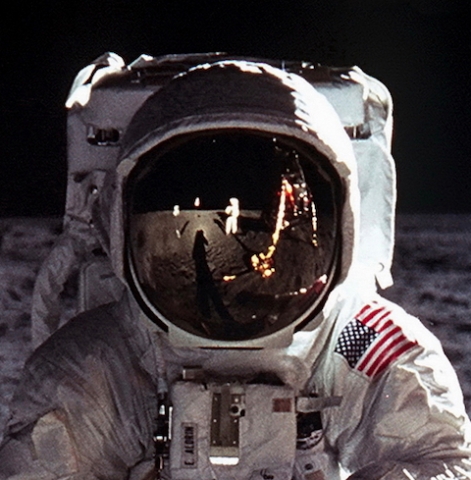

Apollo astronaut Buz Aldren on the surface of the Moon 1969, source NASA

Apollo astronaut Buz Aldren on the surface of the Moon 1969, source NASA

The feat required flying the space craft faster than a speeding bullet (roughly 24K miles per hour) and in the right direction. Integrated circuits, (at the time, very expensive computer chips) were a must, and by the end of the decade, were indeed being produced by Fairchild and Texas Instruments (others?) for literally penny’s per unit.

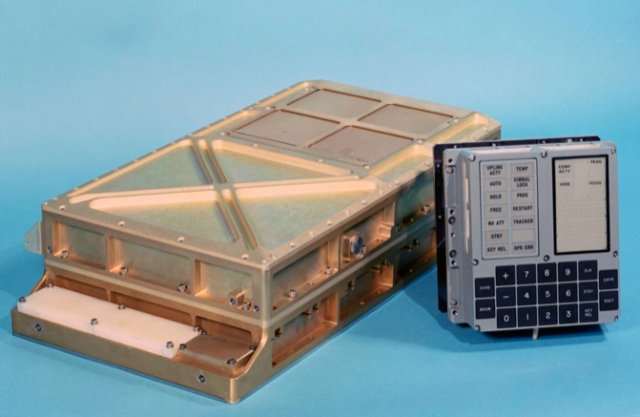

AGC (Apollo guidance computer) from MIT one of two portable computers taken to the moon, Source NASA

AGC (Apollo guidance computer) from MIT one of two portable computers taken to the moon, Source NASA

To get there, real time computing had to be accomplished. In short, a portable (OK, small enough to take to the moon. portable) complex guidance and navigation unit used to process real-time trajectory equations and translate them into guidance commands was essential. In that vein, the AGC (short for Apollo Guidance Computer) was conceived and created at an MIT lab in Massachusetts. (Go Beavers!)

The moonshot consumed massive scientific resources and human imagination and a whopping (4.5- to 5.5% of our national budget (roughly $160B in today’s currency). All this was brought to bear on a host of complex and unknown problems that ranged from human survivability in zero G’s to spacecraft telemetry to guide the way.

And it’s that later problem, that required the development of sophisticated and miniaturized electronics that served to push the foundational research of Jack Kilby (Texas Instruments integrated circuit) and Robert Noice (Fairchild and later Intel – monolithic circuit – or microchip) into mass production that eventually created today’s digital culture.

Most readers (OK I’m assuming) were around that half century ago, to witness firsthand the remarkable televised event. Its significance defined the next generation of children born as having come after man first stepping on the surface of the moon. Remarkably, just ? of American’s living today are old enough to make that claim.

The accomplishment consumed massive scientific resources and human imagination and a whopping share of our national budget and 400K mostly white, mostly male, contractors and support personnel. The challenges were so tough that the term ‘Moonshot’ has entered today’s lexicon as

“…a complex, large-scale objective that can be accomplished only when teams abandon “business as usual.” Moonshots require significant breakthroughs in attitude, innovation, leadership, processes, management, and technology. They demand extraordinary execution and are often marked by seemingly unrealistic time lines. […] My first real moonshot was in the 1990s with the creation of the PalmPilot—the precursor to the smartphone. Lisa’s most memorable moonshot was Nokia’s MOSH, the first big mobile social sharing platform, which swelled to 13 million users in its debut year.” – From wiktionary.com

The achievement was characterized in hindsight by historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. as an event that will be remembered five centuries into the future. Well beyond Pearl Harbor, 911 twin towers or even (yes-the Trump era or even Brexit)

So take a look at that lonely satellite circling our beloved home planet, with fresh eyes some evening soon, and imagine what it would be like if we never had decided to go. How different things may have been and just how wonderful a feat we (OK ? of us) were privileged to have witnessed. – Stephen Sechrist