Did you know there is a Thank God It’s Monday Day? It was January 3. Blue Monday? January 17. No Brainer Day? February 27. National Awkward Moments Day? For many of us, that is nearly every day. Officially, it is March 18—which seems fitting as it comes the day after St. Patrick’s Day, when the Irish celebrate big, and those who aren’t Irish celebrate with them. There are a lot of obscure holidays: Tell a Lie Day (April 4), National Dance Like a Chicken Day (May 14), which follows National Frog Jumping Day (May 13). There’s more, so many more—and for some reason they did not make Hallmark’s list.

One holiday that this industry should be celebrating is National 3D Day. It’s easy to remember: It is held each year on the third day of the third week of the third month. For easy reference, this year it is March 22. (oops – we should have organised to publish this yesterday – Editor) It’s legit—it is listed on the National Day calendar, and this year it shares the designation with National West Virginia Day, World Water Day, National Bavarian Crepes Day, and National Goof Off Day. While some of those “holidays” are to be taken lightly, others, such as National 3D Day, are intended to be taken seriously.

3D is a designated holiday and worth celebrating. (Source: National Day Calendar)

3D is a designated holiday and worth celebrating. (Source: National Day Calendar)

National 3D Day celebrates the art, science, and history of stereoscopic 3D (S3D) imagery. It was established two years ago by 3-D Space, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the stereoscopic imaging through The Center for Stereoscopic Photography, Art, Cinema, and Education, with the goal of recognizing the history and resurgence of the technology.

How much do you really know about stereo 3D, aside from seeing it in films such as Life of Pi, Hugo, Avatar, Gravity, and others? Stereo technology spans many industries and applications, not just filmmaking. It is an important tool in the oil and gas industry, the medical field, industrial design, and so much more. It encompasses cameras and projectors, screens, and displays, glasses and head-mounted displays, and even sound.

The intention of S3D is realism; in simple terms, it is achieved by displaying a pair of slightly offset images that are blended into one, giving it the illusion of depth. Just how well this works depends on the technology and devices being used, as well as the content using it.

First, a history lesson

If you think that stereo 3D is a contemporary invention, think again. Sir Charles Wheatstone invented the stereoscope in the late 1830s to give depth to 2D drawings. The device, which used mirrors, was primitive by today’s standards, but the premise was the same: two slightly offset images could be used to trick the brain into seeing perceived depth. About a decade later, Sir David Brewster built on that setup with a stereoscope, building a device that was lens-based and portable. As the newfangled invention of photography caught on, many became enthralled at looking at 2D photos in stereo.

Wheatstone’s mirror stereoscope. (Source: Wheatstone, 1838)

Wheatstone’s mirror stereoscope. (Source: Wheatstone, 1838)

As the process evolved, photographers were sent to the ends of the earth to capture intriguing images that could be viewed in stereo. There were even companies set up for this particular purpose, among them was The London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company. By the 1870s, however, the novelty began to wane but the pursuit of perfecting the methodology and applications continued.

Eventually, the entertainment value of stereo 3D moved from still images to film at the turn of the century. At this time, audiences viewed a pair of films projected on separate screens though a handheld stereoscope device. In 1903, the Lumiere brothers created a stereo version of their short film “L’Arrivée d’un Train,” showing a train pulling into a station in France. To this day, it still carries the story that the experience sent some in the audience scrambling to escape the “oncoming” locomotive, although this is more likely urban legend than fact.

Antique stereoscope viewer circa 1890s. (Source: Harp Gallery)

Antique stereoscope viewer circa 1890s. (Source: Harp Gallery)

In the early 1920s, audiences no longer had to hold stereoscopes to view 3D films and could use anaglyph-style glasses instead. This process entailed printing overlapping red and cyan images onto a single film reel, and when audiences used a corresponding viewing device, it generated a 3D effect—though at the time, the films themselves ironically were in black and white, not color. A big step forward for stereo 3D films occurred in 1952 with the first 3D color film Bwana Devil, billed as the “first feature-length motion picture in Natural Vision 3 Dimension.”

Interest further picked up in the 1960s, increasing more in the early 1970s with the invent of various technologies and processes, including Space-Vision 3D and Stereovision. The first movie using Stereovision was a softcore porn comedy (go figure) called The Stewardesses.

Once IMAX entered the picture, it became successful in putting seats in its theaters, and still does today. While IMAX continued to popularize 3D films, technologies such as RealD, Dolby 3D, and others also helped fill theater seats with audiences who were now wearing polarized or LCD shutter glasses. Filmmakers were producing 3D content, both actual 3D content and 2D content that had been converted to 3D.

This, of course, is just a brief jaunt through history.

Living life in stereo 3D

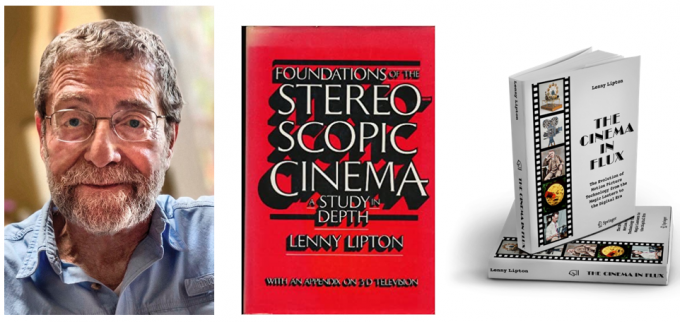

One person whose work has had a lasting impact on various aspects of stereo 3D is filmmaker/inventor/author-lyricist Lenny Lipton, starting in the early 1980s with the founding of StereoGraphics Corp. In 1989, StereoGraphics introduced CrystalEyes for stereo visualization, which was used for medical imaging, aerial mapping, molecular modeling, and so forth; NASA even used it to remotely drive the Mars Rover.

Lipton also was the lead developer of the ZScreen polarization modulator, which enabled a projector to display both the left and right halves of a stereo pair. Introduced in 1988, this technology was used for molecular modeling and aerial mapping visualization. StereoGraphics was later acquired by RealD, and in mid-2000, as CTO, he worked to adapt the ZScreen for use in theatrical projection.

Lenny Lipton (left) has written a number of books, including “Foundations of the Stereoscopic Cinema” and “The Cinema in Flux.”

Lenny Lipton (left) has written a number of books, including “Foundations of the Stereoscopic Cinema” and “The Cinema in Flux.”

A graduate of Cornell with a degree in physics, Lipton has always loved the cinema, and has recently written a book called “The Cinema in Flux,” chronicling the history of cinema technology. At an early age, he developed an appreciation for stereoscopic images, comic books, and movies, especially in the early 1950s when there was a strong commercial push to create stereoscopic cinema. “I lived in New York and had a chance to see a lot of 3D movies then. They made maybe 50 3D movies, but it became swept away by CinemaScope,” he says, noting that 20th Century Fox’s wide-format (2.55:1 aspect ratio) CinemaScope was much easier to project compared to using dual projectors in the booth to achieve stereo 3D.

Thanks to royalties from the song lyrics Lipton wrote to Peter, Paul, and Mary’s “Puff the Magic Dragon” during his early years in college, and later the book “Independent Filmmaking,” Lipton had the freedom to experiment with stereo displays and founded StereoGraphics, whose inventions were geared to engineers and scientists. His system doubled the display rate, allowing the viewer to see all the imagery, not just half of what was available to see. “Our major customers were Lockheed and Pfizer, but we couldn’t find a market beyond [these areas],” he said. This led to the deal with RealD to improve the system to work in theaters. “It was a slick system that combined itself with digital projection and used very inexpensive polarized glasses. The [projected] colors were good, and it was comfortable [for viewing].”

Lipton estimates that to date approximately 35,000 movie theaters worldwide use 3D systems based on his technology. (Source: RealD)

Lipton estimates that to date approximately 35,000 movie theaters worldwide use 3D systems based on his technology. (Source: RealD)

Over the years, there has been a lot of criticism surrounding S3D films, and that rankles Lipton, who points out that stereo 3D films have garnered billions of dollars over the years, especially with the upcharge theaters generally charged for a 3D movie. According to Statista, box office revenue generated by 3D films in the US and Canada from 2006 to 2017 totaled $15.1 billion (USD). “And yet, people laugh at it, they call it a catastrophe, a failure, but that’s not true,” he says.

Moreover, Lipton disagrees with the notion that the public has gone through a rocky, almost love–hate relationship with the genre. “It’s not true,” he says emphatically. “Since my invention was introduced, it has made money steadily—billions of dollars and hundreds of movies made.” Statista’s findings show that in 2006 to 2008, S3D box-office revenue was in $0.1 billion to $0.2 billion, but then shot up to $1.1 billion (all USD) in 2009. The following year saw a huge increase, to $2.2 billion (USD), which led to a peak in the number of S3D films that were released in 2011. While box-office intake remained fairly steady thereafter in the $1.8 billion (USD) range, the number of 3D films being released has been on the decline.

Numbers, though, can be deceiving. According to the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) Theatrical Market Statistics Report for 2020, the US and Canadian box office revenue was $2.2 billion, down 80% from the previous year. Of course, getting seats filled in theaters was rough during the pandemic, even downright impossible as many theaters closed their doors, whether temporarily or permanently, opting for VOD or streaming from their homes. Yet, US box-office revenue was down in 2019, which was pre-pandemic, according to statistics and M&E media headlines. Lipton reasons that if S3D is not making money right now, look no further than the long reach of the pandemic, which kept all movie-goers home. “It’s not that 3D can’t survive,” he says. “The question is, can theaters survive? Now we have a major cinema catastrophe caused by the pandemic.”

While streaming and VOD has satisfied many, S3D at home is not that simple. Whether or not there is a market for S3D in the home has yet to be seen, at least for now. Not long ago, manufacturers were selling stereo 3D televisions—LG, Sony, Samsung—with some products having better results than others. Today, there isn’t as big of a push to manufacture these products.

Back in 2005 or so, Lipton and a colleague had tackled one of the bigger hurdles to S3D by figuring out how to make the system twice as bright. “All the pieces are there; people just need to return to the theater. There is not much that needs to be improved upon [for a good stereo experience],” he says. However, theater owners need to do their part by maintaining the equipment and not pushing lamps past their shelf life, which along with other factors, results in darker images. Content creators likewise have a role to play by generating exciting and compelling stereo images, so audiences are much more willing to pay a few dollars more for an S3D film experience.

History supports Lipton’s view. Avatar, released in 2009, generated substantial buzz for S3D. According to Box Office Mojo, domestically, over 80% of the film’s gross was generated from 3D ticket sales—64% from typical 3D, and 16% from IMAX—two months following its release. Not only is Avatar considered a prime example of 3D filmmaking, but it is also the highest grossing film of all time. With Avatar 2 scheduled for release later this year, and more Avatar sequels to come, it could yet again provide S3D with a big push.

James Cameron’s original Avatar feature film brought audiences to 3D theaters and is considered to be one of the better 3D films in terms of its use of stereo. (Source: 20th Century Fox)

James Cameron’s original Avatar feature film brought audiences to 3D theaters and is considered to be one of the better 3D films in terms of its use of stereo. (Source: 20th Century Fox)

Fun and games

Most people automatically think of films when they hear “stereo 3D.” In fact, many would say movies helped popularize stereo 3D and drive awareness of the genre. “However, from the point of view of interesting content that would make people say, ‘Wow, that’s cool!’ it was 3D gaming,” says Neil Schneider, who has been following S3D in games for many years as executive director of The International Future Computer Association (TIFCA) and founder/CEO of the website Meant to be Seen (MTBS3D.com) since 2008.

Schneider became passionate about the technology after setting up an elaborate stereo 3D gaming system at home many years ago. “Stereo 3D just added a lot more to the whole experience. You put the glasses on in those days and a relatively simple graphics scene suddenly looked visually interesting,” he says. “It added a lot more to the experience. It still adds a lot more to it.”

The rise of 3D in gaming began before the turn of the last century, but in the late 2000s, it was really gaining steam. Schneider says that back in 2008 or so, 3D, at least for gamers, tended to be more technical, and the people were sharing their home brew solutions.

Unreal Tournament 3 using iZ3D 1.08 drivers scratched the early itch for playing games in stereoscopic 3D. (Source: Meant to be Seen)

Unreal Tournament 3 using iZ3D 1.08 drivers scratched the early itch for playing games in stereoscopic 3D. (Source: Meant to be Seen)

During this time, 3D gaming was very much PC-driven. Schneider recalls working with Epic Games VP Mark Rein on a demonstration of 3D gaming using iZ3D drivers to play Unreal Tournament. Afterward, Schneider says, Rein was asked his thoughts on 3D gaming on consoles, to which he replied that he saw it more of a PC thing, especially due to the limited processing power of consoles at the time. Andrew Oliver, CTO of Blitz Games Studios, was in attendance and disagreed. He told Schneider that his studio was developing for the PS3 and Xbox 360 and thought his studio could develop games that could work in 3D on the modern game consoles. Subsequently in 2009, Blitz released the title Invincible Tiger: The Legend of Han Tao, which became the first stereoscopic 3D console game on Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3; it could be played on the 3D televisions at the time. Back then, Oliver had stated that the game was more of a proof of concept and making the game compatible with all the various 3D formats from each TV manufacturer was difficult.

It didn’t take long for SD3 to migrate to gaming consoles. Here, Blitz Games’ Andrew Oliver (left) and Neil Schneider test out a prototype. (Source: Schneider and Meant to be Seen)

It didn’t take long for SD3 to migrate to gaming consoles. Here, Blitz Games’ Andrew Oliver (left) and Neil Schneider test out a prototype. (Source: Schneider and Meant to be Seen)

After this breakthrough, 3D gaming did not take hold as some expected it would. In Schneider’s opinion, in these early days, people were very interested in 3D in films and in gaming. However, he believes content didn’t go far enough in their use of S3D. “There was growing pressure to create 3D content, but it is more demanding to do that, and it requires 30% to 50% more processing power to render a 3D image versus a traditional 2D image,” he says. “So, we started seeing shortcuts like 2D-plus-Depth [a video coding format for 3D displays whereby each 2D image frame is supplemented with a grayscale depth map]. With 2D-plus-Depth, you’re keeping the performance but are getting a pseudo 3D image instead of the full stereoscopic 3D experience that games are excited about.

“Remember, what makes 3D interesting are the unique details and differences between the left and right view; technologies like 2D-plus-Depth lose a lot of this magic,” he adds. “Even with some native stereoscopic 3D solutions, we saw restrictions preventing gamers from doing fun, out-of-screen effects with their games. Users wanted more.”

Possibly a byproduct of the rush to generate 3D content, the conservative methods for creating stereoscopic 3D games and films may have inadvertently soured some user opinions of the format, notes Schneider. 3D films generally were very modest when it came to incorporating S3D, with Avatar being the exception. “If you looked at the early experiences that got people excited about 3D, and then compared to the later stages, there is a marked difference between the two,” he said. “In the gaming world, it was very important to have the full 3D, no-hands-barred experience.”

S3D films have been around for decades, long before Avatar. As long as 30-plus years ago, scientists, developers, and device manufacturers were injecting 3D into games, though many results are not worth discussing.

Does anyone remember Nintendo’s Famicon 3D System (1987) for its Family Computer game console, which comprised a pair of LCD shutter glasses and an interface box? Few do. What about Nintendo’s Virtual Boy console in 1995? You very well may have missed it; it was pulled from the market a year after release due to lack of sales. Its high price tag, ho-hum 3D effects, and lack of 3D games undoubtedly led to its downfall, as was concern that products like this could interfere with stereopsis development in young children.

Nintendo tried to redeem itself in 2011 with the Nintendo 3DS handheld console, which offered stereo effects without the use of glasses, but the road to success was slow going—at least initially. Pricing was slashed by about a third after only six months due to low sales, but to appease those who purchased the device at the original price, Nintendo threw in a bunch of free games to those buyers. This appeared to satisfy the retail gods well into the future, as the Nintendo 3DS family of systems purportedly have sold nearly 76 million units, and 387 games as of September 2021.

Nintendo’s Virtual Boy (left) was released in 1995 and marketed as the first console capable of displaying stereo 3D graphics. It was short-lived. The Nintendo 3DS, released in 2011, could display stereo 3D effects without the use of 3D glasses or other accessories. Although it had a slow start, it eventually became one of the company’s most successful handheld consoles. (Source: Wikipedia)

Nintendo’s Virtual Boy (left) was released in 1995 and marketed as the first console capable of displaying stereo 3D graphics. It was short-lived. The Nintendo 3DS, released in 2011, could display stereo 3D effects without the use of 3D glasses or other accessories. Although it had a slow start, it eventually became one of the company’s most successful handheld consoles. (Source: Wikipedia)

As expected, Sega, Atari, Sony, and others got into the act during that time, too, all with rather dismal results. That is, until the dawn of the console wars.

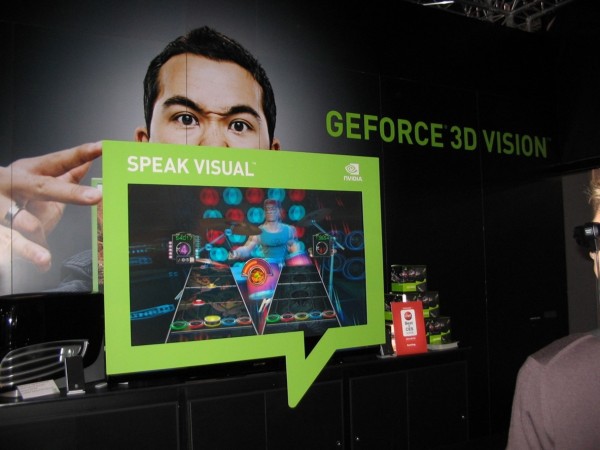

On the PC side, however, it was a different story. GPU maker Nvidia came to play early in this realm and began offering 3D drivers that made it possible to play existing 2D games in 3D. Then, in 2008, Nvidia offered the now-discontinued (after 11 years) Nvidia 3D Vision stereoscopic gaming kit, which comprised shutter glasses and GeForce driver software that enabled stereo for any Direct3D game. Offering users a choice of Dynamic Digital Depth’s Tridef drivers and iZ3D’s software solution, AMD also entered the field a few years after 3D Vision’s hold on the market with the open-platform HD3D supporting its Radeon series cards. As a result of these two giants’ efforts, along with LCD monitors that could refresh at the rate of 120 Hz and support stereo viewing, the number of 3D-supported games rose significantly.

Nvidia’s focus on the PC gaming market led to the sale of its Nvidia 3D Vision stereo gaming kit. (Source: Neil Schneider and Meant to be Seen)

Nvidia’s focus on the PC gaming market led to the sale of its Nvidia 3D Vision stereo gaming kit. (Source: Neil Schneider and Meant to be Seen)

A lot has occurred over the past decade to promote the 3D experience in games, especially since today VR, AR, and XR have entered the picture—but that’s an entirely different and lengthy topic. Meanwhile, Nvidia especially continues to focus on the game market with a range of offerings, including GeForce NOW cloud gaming for streaming up to 4K resolution with HDR. Meanwhile, the company’s GeForce RTX continues to bring unprecedented realism to games like Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege with support for ray tracing and Deep Learning Super-Sampling (DLSS), which applies deep learning and AI to rendering for crisper imagery. One of the most played games on Steam is Dying Light 2 Stay Human, in which players with a GeForce RTX GPU can explore the massive virtual world, with its ray-traced effects and DLSS-accelerated performance.

Meanwhile, AMD cards have set new standards in console gaming. The Sony PlayStation 5, which is at the high end of console gaming, contains an AMD Oberon GPU; the Microsoft Xbox Series X uses a customized AMD GPU based on the RDNA 2 architecture.

“There’s a group of people who, once they experience 3D, love it from the get-go and can’t let it go. They’ll come up with all kinds of hacks and try to get software that’s not designed for [S3D] to work with it—they’ll do anything and everything to get some kind of 3D experience,” says Schneider.

As Schneider points out, today we are in the era of virtual reality, so S3D did not disappear. It’s still very much present in modern VR, and he sees a future ripe with lifestyle-based applications—online experiences that have a solid beginning and an interesting middle, with no ending, as opposed to a game that has a beginning, middle, and end. “Creators have to be careful though. If a virtual reality gamer is expected to invest a lot of time in VR, it can’t feel like work!” he says.

“What got people really excited about stereo 3D was the real stereo 3D, not conversions or 2D-plus-Depth in gaming. While there have been amazing advances with these technologies, if you’re going to do conversions, you’re going to get a conversion result. Conversions weren’t invented because creators wanted better 3D—they just wanted more 3D products. I’d rather see more amazing native 3D pieces of content than lots of pseudo 3D content. Quality over quantity,” Schneider says.

3D on Display(s)

S3D was on a roll more than a decade ago, and this applied to film and TV, as well as games. TV channels were featuring 3D broadcasts of sporting events, which helped the sale of 3D televisions. Manufacturers such as Sony and Samsung introduced 3DTVs that required shutter glasses, but without standards, one company’s glasses were incompatible with another’s product. And these glasses were not cheap, nor were they very comfortable and were relatively heavy, notes Bob Raikes, writer/editor at Display Daily newsletter and managing director of market research consultancy Meko. Unlike its competitors, LG took a different approach, using spatial separation, “and that worked well,” contends Raikes.

Yet, due to the lack of standards, competing systems that were very expensive and not well marketed, and a small amount of 3D content available, 3DTV did not win customers. “With 3D broadcast, ideally you need to send twice as much data, and that costs money,” says Raikes. Perception also plays a part. “The brain looks at a 3DTV soccer match, for example, and it wonders, why are those tiny men playing soccer in that fish tank, instead of imagining what you’re seeing is the real world through a window. Issues like that must be resolved.”

Philips is among the manufacturers that entered the 3DTV market. (Source: Philips)

Philips is among the manufacturers that entered the 3DTV market. (Source: Philips)

As a result, manufacturers began moving away from producing 3DTVs and instead focused their efforts on 4K TVs.

As for monitors, as far back as 2008, 3D monitors were being made by companies like iZ3D and Zalman for playing DirectX 9 games. But it was a lawless time, and without any APIs and standards, the drivers had to be hand-tweaked for each game since game developers were not involved in making their games work on these 3D screens.

There are three types of 3D displays: active and passive, which require 3D glasses, and glasses-free (autostereo).

Autostereoscopic display technology can use lenticular lenses, a parallax barrier, holography, light fields, and volumetrics. Volumetric displays form a visual representation of an object in three physical dimensions, as opposed to the planar image of traditional screens that simulate depth through visual effects. With a volumetric display, a person can view an object from any direction. They are used mostly in the professional realm, such as medical imaging, simulation, and geophysical visualization, albeit in small numbers; they are not intended for the consumer space, Raikes notes.

With Looking Glass Factory’s holographic display, users can see images in stereo without the use of glasses. (Source: Looking Glass Factory)

With Looking Glass Factory’s holographic display, users can see images in stereo without the use of glasses. (Source: Looking Glass Factory)

Shawn Frayne is CEO of Looking Glass Factory, which builds desktop and personal holographic displays. He believes that as more content is created in 3D by individuals and businesses, as is happening at an accelerating pace now, there will be more demand for new ways to share and consume that content. Displays that have advanced stereo 3D capabilities (without glasses) will have a growing role to play as this shift from 2D to 3D rolls on, he says.

Frayne obviously is a proponent of being glasses-free. “I could say the same thing about 3D glasses that Steve Jobs said about smartphone styluses 15 years ago: ‘You have to get ’em, put ’em away, you lose ’em.’ No one wants 3D glasses.”

He further contends that those industries that create in 3D today will be the first to adopt glasses-free 3D holographic light field displays. “They already have the content in a native 3D format, and that’s a prerequisite for being an early adopter of displays with 3D output and interaction capabilities,” says Frayne. That includes experiential agencies working with 3D engines like Unity and Unreal, engineering firms working with various CAD platforms, and animation studios and individuals drawing and sculpting in 3D today. Medical and scientific visualization companies are also in that mix but will be a bit slower to adopt due to regulatory reasons, he adds.

Where is 3D headed when it comes to displays? Raikes admits initially he was skeptical about the adoption of S3D because of its impracticalities. “I’ve been in this space for close to 40 years, and about three years in, I came up with Bob’s law, which says that everything that increases visual bandwidth wins in the end. And 3D will increase the visual bandwidth, so it will happen. I am absolutely convinced of that, but I’m not sure if I’ll be alive to see it happen commercially,” he says. “Everyone always thinks whatever we have at that time—high frame rate, HDR, wide color gamma—is good enough.” But then, it isn’t. “In the end, 3D is going to be there because if we throw away depth information, we are throwing away information, and the human visual system is a communication [mechanism] that gives us information, and if we don’t capture all the information that’s possible, we are not having the maximum experience. On that basis, everything must go through in the end.”

To get there, Raikes contends we need massive amounts of pixels. And then there is the chicken-and-egg problem: If you do not have content, then what’s the point in having S3D screens? And if you do not have good displays, how do you get the content? One thing that could change that is VR, he says, as people become more comfortable with viewing two separate images, one for each eye. “Once people have a compelling experience they cannot get on their flat screens, that could drive production,” he says. Yet, the issue remains of the sheer amount of pixel data and bandwidth that is necessary.

Frayne sees a bright future for stereo 3D displays. Nothing, he says, is standing in the way. Costs are no longer prohibitive, glasses are no longer needed, and quality has passed the critical threshold. That said, 3D “stuff” (media, programs, models) comes in so many different formats, and “we as an industry do need to make a concerted effort to get all that content to play nice with any device. I’m talking truly multi-platform standards. Until that happens, the pace of adoption will be slower than it would otherwise be,” he points out.

Those who wear glasses…

As far back as the early 1920s, stereo 3D was achieved with anaglyph glasses, then came polarized glasses. Around 1940, the plastic View-Master toy for stereo picture viewing was released, giving many their first entry into S3D.

Anaglyph glasses, those cheap paper glasses with one blue and one red lens, create the perception of depth when used to view an anaglyph image (the combination of two images: one with a red filter and the other with a blue filter). Even today, this technology is used for 3D viewing of comic books and other materials in the print medium. Polarization, however, upstaged anaglyph in film, as the glasses provided more accurate color viewing and made stereo 3D viewing more comfortable. They work by restricting light that reaches each eye using different polarized filters. Polarization is the choice du jour at theaters.

In 1989, StereoGraphics introduced CrystalEyes for stereo visualization.

In 1989, StereoGraphics introduced CrystalEyes for stereo visualization.

It’s important, too, to recognize shutter glasses. There are two types of glasses: active and passive. Active shutter glasses are made of LCD shutter lenses that run on a power source and use a timing signal to alternately block one eye and then the other in quick succession and in sync with the refresh rate of the screen. More expensive, these glasses are commonly used with most consumer 3DTVs, projectors, and PCs/workstations; they are also used in theaters and with some visualization systems. (Lipton, in fact, developed wireless active shutter glasses for StereoGraphics in the late 1980s.) Passive glasses are made of polarizing lenses similar to those often used in movie theaters and amusement park rides. Each image is polarized to match one passive eyeglass lens, and each image is then shown to each eye at the same time—no power source needed.

According to Neal Weinstock, an experienced player in stereo devices and screens, the RealD system uses a polarized switching liquid crystal in front of the projector, allowing viewers to wear passive polarized glasses. The shutter glass system does not use a filter in front of the projectors, but rather an active liquid crystal shutter in front of each eye. The effect, he notes, is basically the same; it just involves placing the active LC switch in a different location. “The difference is really between passive (cheap) glasses plus an expensive shutter system in front of the projector, and active (more expensive) glasses with no expense in front of the projector,” he explains.

The recent rise of AR, VR, and XR has resulted in head-mounted displays and headsets such as the HTC VIVE and Oculus Quest and Rift. There are also options that utilize an attached smartphone to achieve VR viewing.

The Oculus/Meta Quest 2 is a popular device for 3D gaming. (Source: Oculus/Meta)

The Oculus/Meta Quest 2 is a popular device for 3D gaming. (Source: Oculus/Meta)

Weinstock entered the 3D market in the mid-2000s and started Soliddd, an optical technology company introducing an autostereo display system they are marketing for printed advertising posters. The company continues to innovate with AR and VR monitors and eyewear; it is working with licensee Orga FPV and soon will be releasing a single-element lens, focus-free AR/VR system with a pair of glasses similar in thickness and comfort to everyday glasses and will be in focus no matter the wearer’s visual acuity.

“Soliddd does AR and VR displays and sensors. Our optics fit anyone’s eyes without adjustment, with broad eye-box and eye relief, and are very comfortable. If you normally need corrective eyeglasses, you don’t need to wear them for our system,” Weinstock says. “We use our lenses to improve both the display and for 3D positioning capture in cameras, and we’re using them first in cameras together with displays and headsets for strongly improved gaze tracking and much more efficient foveated rendering. It’s an integral imaging system for both capture and display. We have optics that fit close to the eye, and we do a combined system with this tracking as well as our integral imaging lenses that fit over the display.” Integral imaging captures and/or reproduces a light field using a 2D array of micro-lenses.

Looking ahead, Weinstock expects to soon see 3D displays for the naked eye—meaning no glasses—being used at airports and shopping malls as advertising and informational vehicles. Meanwhile, users of S3D today can be found mostly in the science and technology realms. In terms of home use, Weinstock believes that 3D consumption in the home will take some time. How much value will someone get from a high-end 3D display for normal entertainment is the question right now. Perhaps gamers, itching to play the latest 3D title, will change that dynamic.

Many people assume that S3D is on the decline, a notion disputed by some experts. Stereo 3D is popular in movies and gaming, and is an important tool in the professional realm.

Many people assume that S3D is on the decline, a notion disputed by some experts. Stereo 3D is popular in movies and gaming, and is an important tool in the professional realm.

Did ya know?

Many people think stereo 3D is relatively new. They are wrong. It has been around for well over a century. Another misperception: The public’s interest in S3D has come in peaks and valleys. Again, not so, contends longtime stereo 3D inventor Lipton, although there have been times of greater growth. Are 3D glasses holding S3D back? While some glasses offer a better experience than others, this is hardly the case.

As Jon Peddie, president of Jon Peddie Research, points out in his book “The History of Visual Magic in Computers,” for applications such as CAD and medical analysis, S3D is an important and necessary capability. For commercial applications such as signage, it can be helpful. In entertainment systems—cinema, TV, PCs, and mobile devices—it can enhance the user experience.

So, what can be done to push S3D into the next realm? The experts I talked with agree that good stereo content is needed. And by that, they mean well thought out stereo and meaningful 3D that enhances the story, not the gimmicky moments of having an object pointing at your eyeball, although some, like Schneider and his army of 3D glasses-holding gamers, love that stuff.

We have been on a 3D trajectory for quite some time both commercially and personally, and no doubt that will continue. Meanwhile, let’s celebrate how far S3D has come as we look to its next chapter.

S3D is no longer a singular subject. Today, it has many branches, and those branches have grown branches and leaves. The subject matter of S3D is extremely large, and to cover it all in one article meant just scratching the surface. Hopefully, it has piqued your interest in this growing medium and will encourage you to dive deeper into the various aspects of S3D. So, go celebrate this amazing technology. Eat a piece of cake. Drink a glass of champagne. See a 3D movie. And, have a happy 3D Day! (KM)

To celebrate 3D Day, we moved this article outs

Karen Moltenbrey, Jon Peddie Research

603.432.7568

[email protected]