Today, I’m going to talk about something that’s not directly a display topic, but is a potentially significant display use case. That is to say, autonomous vehicles, and, in particular, cars. If your interest in Display Daily is just in display geekdom, skip this one. The topic came to the top of my idea list after an interesting UK development.

Technology forecasters love to talk about drivers (not car drivers, but drivers of behaviour or demand) and enablers. For any market or technology to develop you need drivers that will make people or corporations want or need to buy the product and there are lots of things that either need to be in place to allow the market to grow. Those are the enablers. For example, in electric cars, there are a number of drivers including a desire to be ‘green’. An enabler is the charging infrastructure to allow a car to be a practical proposition.

For autonomous vehicles, there are plenty of drivers – who hasn’t bemoaned the time wasted in traffic queues? It would be a much better use of time to be looking at a great OLED or miniLED LCD display (or microLED etc) at some great entertainment or educational content.

However, there are also a lot of enablers of autonomy. Many of those are technological, including giving vehicles the ‘senses’ and ‘intelligence’ to be able to work out what is happening around them and how to respond to their environment. But there are also non-technical enablers including the difficult ethical question of what an autonomous vehicle should do if it foresees injury to someone, inside or outside the car, and more particularly, if it can foresee both.

That’s beyond this article, but one of the enablers is the legal framework for autonomous driving. If there’s a crash, and there will be crashes, who should bear the responsibility? This is not a trivial question as the liabilities for injuries can run into millions of whatever currency you can think of.

The UK is Thinking of a Legal Structure

What triggered this article at this time is a recent decision by the UK law commissions (which are advisory to government, but don’t make the laws) to recommend that there are a number of important principles that need to be followed. The first is that the driver, or ‘user-in-charge’, (UIC) as they won’t be driving, should not have responsibility for legal offences such as dangerous driving, speeding or running a red light. The UIC will be responsible for issues such as insurance and ensuring that passengers are using seatbelts.

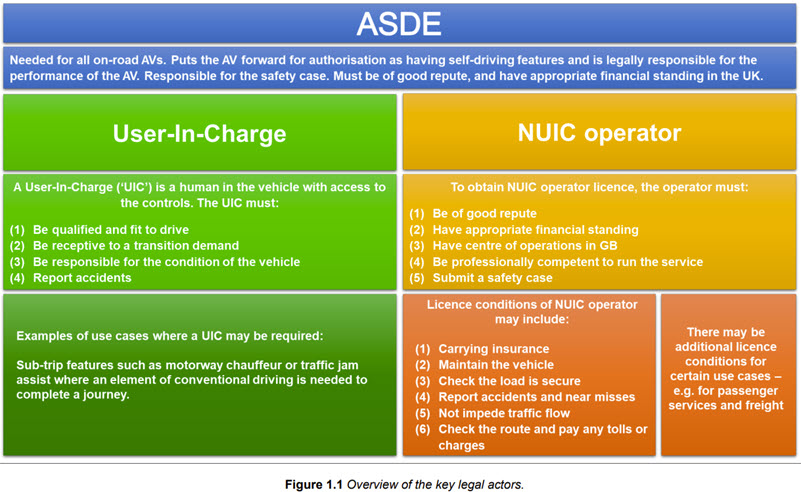

So who would be responsible under this kind of regime? According to the report (which can be downloaded freely here), a new kind of legal entity would be created, an Authorised Self-Driving Entity (or ASDE) that would have to take responsibility. An ASDE would have to put the vehicle forward for authorisation and take responsibility for its actions. This gets around issues of authorities having to arbitrate between the multiple actors involved in designing and developing the vehicle and its components. (although I can imagine a good living for a class of lawyers acting behind the ASDE to try to allocate liability!).

The UIC would have some liability if, after being given a ‘transition demand’ by the vehicle to take over manually, they did not take over. For example, if the vehicle decided it needed to hand over in a ‘no stop zone’, if there was no response from the UIC. An offence might be committed if the vehicle decided that the safest thing to do was to slow and stop – and it will be legally obliged to take the safest action – and if the UIC did not take over.

What About Empty Vehicles?

For vehicles that have no driver, a “no user-in-charge” (NUIC) operator would be required to be responsible for overseeing the journey. The report highlights the challenges in working out how this is best done and the human factors challenges of remote operation in, for example, accurately assessing speed and distance via a display as well as dealing with operator boredom. (It occurs to me that this kind of application could be a great one for displays that showed depth such as autostereo 3D displays).

The UK already has an ‘Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018’ that specifies that victims who suffer injury or damage will not need to prove that anyone was at fault. Instead, the insurer will compensate the victim directly.

Data and Accident Investigation

Another interesting aspect is that there will be a ‘duty of candour’ intended to promote a ‘no-blame safety culture that can learn from mistakes. There would be legal obligations to provide data and system information in the event of accidents, with a view to developing the kind of system used in air accidents. (my words).

In December, following the release of a Mercedes with level 3 automation (for hands-off automated driving in traffic at speeds up to 60 km/h on German motorways), the European Transport Safety Council called for an EU-wide authority to conduct forensic analysis of crashes involving automated vehicles on EU roads. The UK and US are also looking at this kind of authority and in the US, the National Transport Safety Board (NTSB) has investigated several collisions involving Level 2 assisted driving systems, and provided useful recommendations to manufacturers. The Netherlands has taken a leading role in investigating collisions involving automated systems and researchers recently found a method for accessing in-vehicle data without the manufacturer’s involvement.

You have to have a lot of imagination in this kind of legal discussion to minimise ‘unintended consequences’. The report points out, as an example, that

‘where a group of people picked up an automated pizza delivery vehicle and put it in a ludicrous place, such as the top of a bus shelter, where it could no longer function. Under the current law, this would not appear to be a criminal offence.’!

So, progress is slowly being made in dealing with some of the enablers of autonomous driving. However, there are a lot more to go and we’re now getting to the kind of time scales that the automotive industry generally thinks are likely to allow the roll out of the full ‘level 5’ vehicle automation, rather than the kind of speed expected by the technology companies and forecast in the past. (BR)

(Outside Europe, developments continue and in January, Caixin reported that in Shenzen, all main roads would be opened for city-wide testing of autonomous vehicles after an earlier opening of a smaller area.)