Following the return of schools to semi-normalcy as Covid shifts from a pandemic to an endemic, I’ve been wondering what the impact will soon be on the return of virtual reality to its previously favored position as a technology darling in education. To get a sense of what’s happening, I’ve had my feelers out to schools, and have been watching what has been emerging from recent national ed-tech conferences. I recently reported on a slight surge of interest in VR in terms of conference session offerings at FETC in my previous article, but now is the time to lay my thinking out. And, unfortunately, it’s not all good.

Although virtual reality learning and physical learning centers will continue to persist in university medical schools (medicine, nursing, dentistry, etc.), the outlook for VR in K-16 settings appears much more dispiriting. Although VR hardware and display technologies continue to evolve and improve at the margins, the true reckoning for VR in the education market lies with its supportive ecosystems and customer perceptions.

The first ecosystem that portends either dayspring or dusklight for VR is content. I offer five reasons why the content landscape continues to molest a positive VR trajectory in the education market:

No Killer App. What we need is the ChatGPT of virtual reality. There just isn’t any. I just cannot see any content that makes virtual reality a “must-have” in the minds of mercurial and crisis-challenged educators.

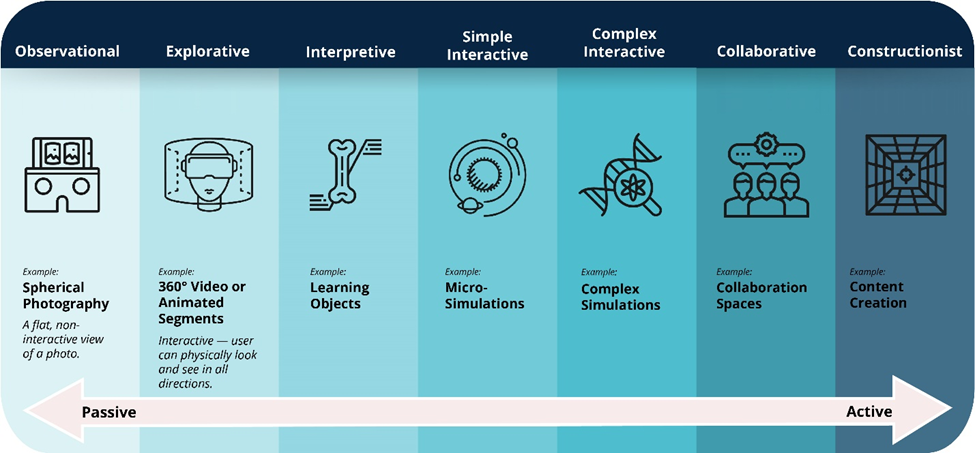

Low-Level Content. Most commercial content for K-16 VR finds itself at the lowest (passive) tiers of my taxonomy of active versus passive uses of VR shown below.

To appeal to front-line educators, and to guarantee sustainability over the long haul, most content needs to transition towards more active student learning. It’s just not there yet.

Lack of Curricular Span. Most VR content touches on the subjects of science, social studies, and some of the arts. Other subjects have little or no footprint. Although science content seems to lead the way in VR content, most non-educators fail to recognize that the available VR content that does exist for science education covers less than 1–2% of the taught science curriculum in schools. With a curricular footprint so small, it is unreasonable to imagine big things for VR in schools. Currently, VR is still a gimmick.

High Prices. With new innovations, there is always a danger that impatient companies will race to the highest price point before the industry has a chance to get its legs. Currently, VR content is priced way beyond the resource level of most schools. On top of that, annual subscriptions worsen the situation. This is called a “pricing failure” in economic terms. Pricing matters in education.

Which Comes First: Chicken or the Egg? Of course, the chicken-or-egg causality dilemma has become cliché for our field. But in the emergence of new technology, content does matter. If you build it (hardware), they (content) will not always come. This attitude puts the whole industry on its back foot in terms of fortuitous development.

In my next article in this series, we will identify more ecosystem challenges—some environmental and structural impediments—slowing the expansion of VR in education.