The lifetime of OLEDs based on thermally-activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) has been ‘greatly’ increased via a ‘small tweak’, say researchers at Japan’s Kyushu University. The modifications, which are easily implemented, can also potentially raise the lifetime of existing OLEDs in smartphones and TVs.

Typical OLEDs are based around an organic molecule, which emits light when a negatively-charged electron and positively-charged hole meet on it. Until recently, all OLEDs were fluorescent (low-cost but with only around 25% efficiency), or phosphorescent (100% efficiency but using expensive materials such as platinum or iridium).

Kyushu researchers demonstrated new emitters, based on TADF, in 2012. TADF materials can convert ‘nearly all’ of the electrical charges into light, without using rare metals. However, there is still the issue that OLEDs under constant operation degrade and become dimmer over time.

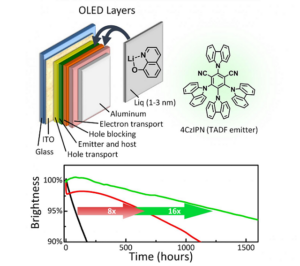

Kyushu’s first TADF devices lost around 5% of their brightness after just 85 hours. However, the new change to the device structure has raised that life by more than eight times.

Kyushu placed two thin (between 1nm and 3nm) layers of the lithium-containing molecule Liq on each side of the hole-blocking layer. The layers bring electrons to the TADF material (the green emitter 4CzIPN, in this case) while also preventing holes from exiting the device before contributing to emission.

The devices will last even longer under real-world conditions, as tests were performed at extreme brightness levels to accelerate the degradation. Additional optimisations, which were not detailed, lengthened the time to reach the 5% brightness drop to more than 1,300 hours.

Researchers found that improvements could also be made using a similar device structure with a phosphorescent emitter.

Liq layers contain a much lower number of ‘traps’: a type of defect that can capture and hold a charge, preventing it from moving freely within the device. These defects were observed by measuring the small electrical currents – created when charges were frozen in the traps at very low temperatures – escape, by receiving a ‘jolt’ of thermal energy as the device is heated. This process is called thermally-stimulated current.

Having charges stuck in traps ‘may’ increase the chance for interaction with other charges and electrical excitations that can destroy the molecules, and lead to degradation.

The next major challenge facing TADF is the creation of stable and efficient blue-emitting materials.

Analyst Comment

This is the second OLED development from Kyushu University in the same week; the first was OLED Emits RGB From Same Materials. Both deal with the layers of an OLED device and are aimed at increasing efficiency, but accomplish this in different ways. (TA)