The “Creatives” in the motion picture industry have always taken technology, sometimes reluctantly, and used it to tell stories. Some of the technologies incorporated over the last 100 years into the cinema include sound, color, digital special effects, digital production and post-production, electronic projection, 4K resolution, High Dynamic Range (HDR), etc. Other technologies embraced by the cinema industry include distribution not just in the theater but also on TV, VHS/Beta tape, DVD, Blu Ray and streaming to a wide variety of display types. Sometimes, Creatives need to be dragged into the modern world.

For example, Harry M. Warner, President of Warner Brothers Pictures, is said to have said about sound films in 1927, “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?” The fact that he may never have said it and, if he did, he wasn’t a creative anyway, need not bother us here.

Yet one technology, now almost 100 years old, is stubbornly retained: 24 frame per second acquisition and display. The Film Look was vigorously defended by Creatives after the 1999 demonstration of digital cinema. To someone brought up television and who worked on high resolution (720p and 1080i), high frame rate (60Hz) displays and content since 1992, the film look always looked like a collection of fairly severe artifacts. These included film weave, film grain, dust and scratches on the film, dim images, low contrast, motion blur and judder. Digital acquisition, digital post production, digital distribution and digital projection have made most of these artifacts go away by 2020. The last major artifacts left over from film days now practically defines “The Film Look” are motion blur and judder. There is a well know solution to these artifacts: high frame rate (HFR).

One of the arguments against HFR is its cost. To go from 24 frames per second (fps) to, for example, 60fps would increase the amount of data in a motion picture by a factor of 2.5x. This would affect the entire content creation and distribution chain including acquisition, post-production, storage, bandwidth for distribution, etc. This increase is actually a non-issue: studios see no particular problem with 4K with its 4X increase in the amount of data or even with 8K with its 16X increase in the amount of data. Storage is cheap – my laptop has a 250G SSD and a 1T Hard drive internally plus a 4T external drive for backup. Another common solution, especially for distribution, is spatial compression and temporal compression is equally possible. In fact, temporal compression is not only possible, it is used for virtually every means of distribution of motion images, except distribution to digital cinemas.

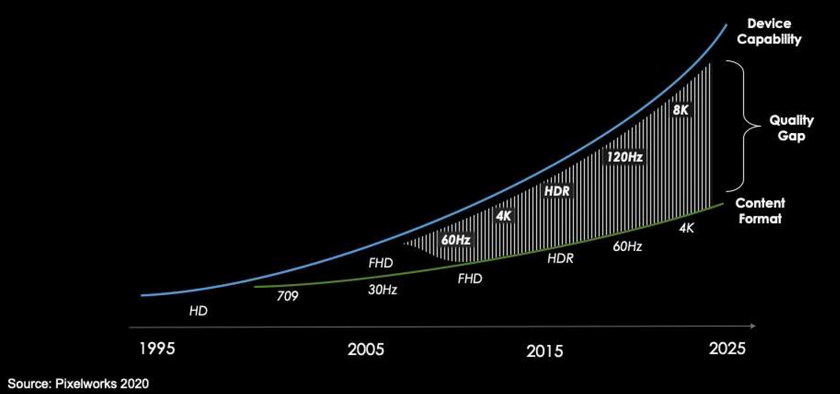

Quality Gap between content formats and display capabilities (Credit: Pixelworks)

Quality Gap between content formats and display capabilities (Credit: Pixelworks)

Pixelworks has pointed out there is an increasing gap between the image quality of motion picture content format as distributed to theaters and, especially, to consumers, and the quality of the image the display device can show. Consumers now have 8K displays with 120fps display rates but cinema content is received at 24fps as SD (DVD) 1080p (Blu Ray) or sometimes 4K resolution. This, not surprisingly, produces judder at the TV screen. TV makers have introduced temporal upscaling to increase the frame rate to 60fps for display, virtually eliminating judder. Film creatives and aficionados have a derisive term for this lack of judder: the Soap Opera Effect.

The UHD Alliance has created a special “Filmmaker Mode” to turn off this motion processing and show the content as the Creatives had intended it: 24p with serious judder. Of course, an alternative if your TV is not equipped with Filmmaker Mode is to go into your TV’s setup menu and turn off motion processing. This motion processing cannot be eliminated from the TVs by the set makers because others, especially sports fans and gamers, really like the smooth motion it can provide. Some people even appreciate the smooth motion in motion pictures as well.

![]() Judder acceptability as a function of pan speed and peak white brightness (Credit: Pixelworks)

Judder acceptability as a function of pan speed and peak white brightness (Credit: Pixelworks)

High Dynamic Range (HDR) content is bringing the judder issue to a head, as shown in the image. At 48 nits brightness, the standard for normal motion picture theaters, judder is judged as acceptable at a 7 second pan rate. This means if the camera is panned so an object in the background crosses the screen in 7 seconds, or if a moving object crosses in front of a stationary background in 7 seconds, the judder is judged acceptable. For extended dynamic range with 108 nit brightness, used in some theaters, the pan rate must be slower than 10.5 seconds to have acceptable judder. For an HDR TV with 1000nits peak brightness, the pan rate must be slower than 21 seconds to produce acceptable judder. If the content creators stick to this limit, 8K HDR viewers wind up watching content with virtually no motion in it.

One of the issues with judder and other motion artifacts is it is different, depending on how the content was acquired. An expert can tell if 24fps content was originally acquired on 24fps film, a 24fps 4K camera or a 60fps 4K camera, or if it was originally created inside a computer. The motion artifacts for these are all slightly different. This can be jarring to the Creative, an expert or a film aficionado with a good eye watching the movie.

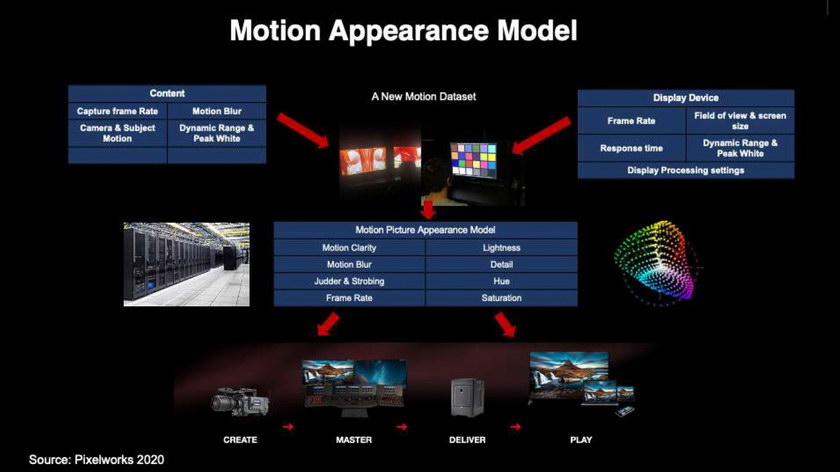

Elements of Pixelworks’ Motion Appearance Model (Credit: Pixelworks)

Elements of Pixelworks’ Motion Appearance Model (Credit: Pixelworks)

To address this issue, Pixelworks has created a Motion Appearance Model to take all relevant factors into account, including whether the movie will be shown in HDR or not. They have then created what they call the TrueCut Motion Tool to apply this model at the post-production model, typically after color grading of the movie. This tool then massages the motion artifacts, a process Pixelworks calls motion grading, so they are uniform from scene to scene. The artifacts are not eliminated – the Creatives overseeing motion picture post-production don’t want them to be gone.

Typically, up to 9 versions of a film are created from the master, for use in SDR, EDR and HDR cinemas; plus versions for distribution on DVD, Blu Ray, streaming, etc. According to Pixelworks, the judder can be controlled to look roughly the same from version to version and be acceptable even in HDR cinema locations with relatively high screen brightness. The motion tool doesn’t just work at 24fps – it has been used to motion grade 48fps material in China as well. The tool is designed to maintain creative intent so the motion artifacts in 24fps, 48fps, 60fps and 120fps versions of a movie all look the same, i.e. they all look like the movie is 24fps.

(Credit: Warner Brothers)

(Credit: Warner Brothers)

Not being a motion picture Creative or a film aficionado, I still think the right solution is High Frame Rate, preferably 48fps or 60fps. I think it is silly to cling to a nearly 100 year old technology to give a “film look” and still adopt 4K resolution, wide color gamut, high dynamic range and multi-channel surround sound. My position is that if you want a good image, you want a good image in all respects. I know none of these things are needed for story telling: just look at Casablanca shot at 24fps on black and white film with about 100:1 dynamic range and about 1K resolution. Personally, I think it tells one of the best stories ever told by the cinema industry. – Matthew Brennesholtz